By Stephen Thompson

I’ve long enjoyed the Deben estuary – my “hole in the water lined with wood or fibreglass into which you pour money” lives there (or to be strictly accurate, it lives propped up on wooden blocks in a yard beside the Deben while I fettle it). However I’d never actually seen a paper copy of “The Deben” magazine until very recently. It’s very impressive – and in particular the photographs and paintings of this gorgeous area. The beautiful scenery reflected in the mirror surface of still waters capture the peace and tranquillity.

But my own interest in such locations has always been driven by a desire to know what’s happening “on the other side of the mirror”. I think this probably started watching Jacques Cousteau on “The World About Us” on Sunday evenings (and if you can remember that, you really are dating yourself!), and poking about in streams and ponds to see what was down there. Fishing, and later on SCUBA diving, fed this ambition, and when it came time to choose I selected a Marine Biology degree.Whilst completing that I realised the importance of truly sustainable utilisation of natural resources, the need for both sound knowledge and wisdom to underpin such management, and that people are actually a very important part of the ecosystem. I carried this approach through a career working in commercial aquaculture, largely in the Mediterranean, and have now brought the same approach to my work at Eastern Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority – Eastern IFCA. (One thing I have learned of late is that people in this field talk in acronyms and abbreviations!).

As the name implies, Eastern IFCA has a remit to ensure both sustainable fisheries and compliance with the requirements of conservation legislation, in an area stretching from The Humber to Harwich, and six miles out to sea. The Suffolk estuaries – as well as being very beautiful – are very important to both aspects of our work. They carry designations as protected areas for several species and habitats, they act as very important nurseries for a range of species including some that are of great importance for local commercial and recreational fisheries and the entire marine ecosystem, and they harbour adult fish that are of direct interest to these fishers.

An iconic species which well illustrates many aspects of that importance is the Bass – beloved of recreational anglers, commercial fishers, chefs and restaurant goers alike.

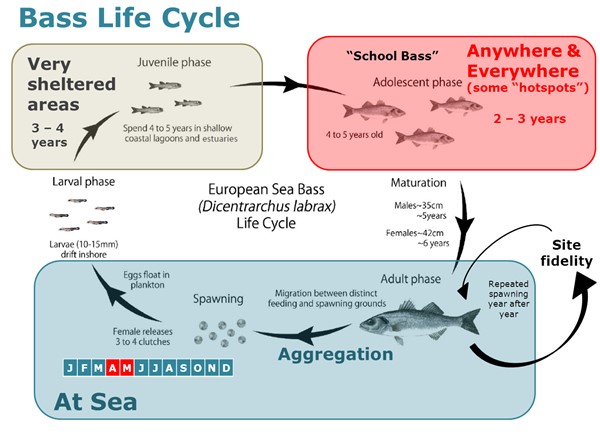

Bass are very versatile fish, living in a variety of environments and showing catholic taste in prey. They do however have a need for nursery areas with particular characteristics, and this is where estuaries and sheltered inshore waters are very important.

Bass come together in spawning aggregations prior to and during spawning. There is now convincing evidence that, at least in some years, bass spawn in the North Sea, with the fish aggregating in late winter and spring to do so. The tiny (about 1 mm) eggs hatch in a few days, and the larvae – looking very different to the adults – drift into inshore and sheltered areas such as estuaries and saltmarshes. At this stage, the larvae are very small and comparatively fragile – they are vulnerable to physical factors such as storms and cold weather, and can succumb to starvation quickly if their required food of zooplankton is not available in sufficient amounts. Once in their nursery areas, the fish change into small forms of their familiar shape and colour; feeding on a wide variety of worms, crustaceans and other small animals they grow over the several years they spend in these areas. The shallowness of the water means that they can be very vulnerable to severe weather, with a sudden cold snap either driving them out, or causing appreciable mortalities.

As there are relatively limited areas which provide suitable nursery conditions, the areas that do exist are very important in supporting the bass population over a much wider area, to which the adults from the nursery areas will move as they mature.

Bass (in common with many fish) tend to “play the Lottery” when it comes to breeding, producing very many – literally millions, for a large female – eggs, each of which has a very low individual chance of survival to adulthood. Due to the susceptibility to a range of factors such as cold and food availability in the early years, bass tend to show some good “year classes” when all the stars have aligned, and a combination of favourable circumstances has meant that there is good survival through to adolescence. Other years are poor, with low survival meaning there are relatively few fish coming through to spawning age. This factor greatly complicates management of the species, as there tends to be “bulges” in the population which can give the impression that the stock is abundant, whereas in fact that may be the result of one good year out of as many as twenty poor year classes.

As a local person, you probably have favourite places, to which you return time after time. We probably all understand that this is also true of the birds in our gardens, as we see the same blackbirds and robins time after time. But it might be surprising to learn that the same applies to bass. Relatively recently, sophisticated tagging using devices which respond to sonar “pings” and uniquely identify individual adult fish into which they have been implanted have shown that the same fish often return to the same small – garden sized – piece of sea time after time, over periods of years and even after months away from the area. Even more impressively, scientists have examined the isotopes making up the bodies of small fish, and by examining the same isotopes in food sources over expanses of salt marsh, been able to demonstrate that even juvenile fish are associated with one particular patch of saltmarsh, to which they repeatedly return after they have been forced to leave by the falling tide. This attachment to particular locations has implications for management – protecting “our” bass is likely to pay dividends in the future, as they will come back. And any actions that degrade the value of a particular piece of saltmarsh, or the ability of fish to get in and out with the tides, will have an impact – the fish can’t just go somewhere else; they are now in effect homeless.

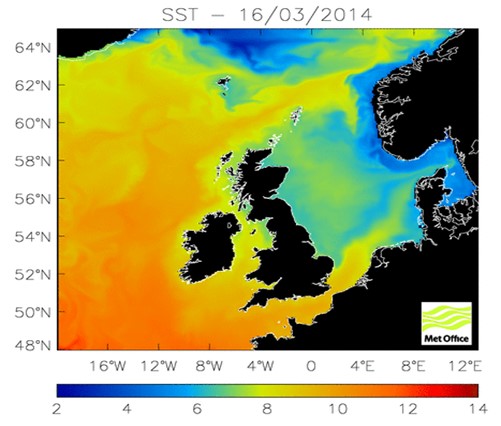

I have mentioned that bass are susceptible to cold, especially in winter. The temperature of the seawater is one of the major factors in determining what lives in certain areas – as the vast majority of sea creatures are cold blooded (to be strictly accurate, their body temperature is the same as the surrounding water), levels of activity, growth and even survival are very dependent on the sea temperature. In this context, Suffolk is in a very interesting location. The image below (from the European Environment Agency) shows the sea surface temperature on a day in mid March 2014, as measured by orbiting satellite.

There is a plume of relatively warm water which extends from the English Channel and into the southern North Sea, and the border with the colder waters of the North Sea lies within the Suffolk coastal area. (Incidentally – while the water coming from the English Channel is “relatively” warm, I can absolutely state that the water off the North East coast of England is definitively cold. Remember I said I learned to SCUBA dive? Well, that was off the County Durham coast, and if I’d seen this image then it would have confirmed what I thought every time I went into the sea there. North East England – not the North of Scotland – has the coldest seas around the UK).

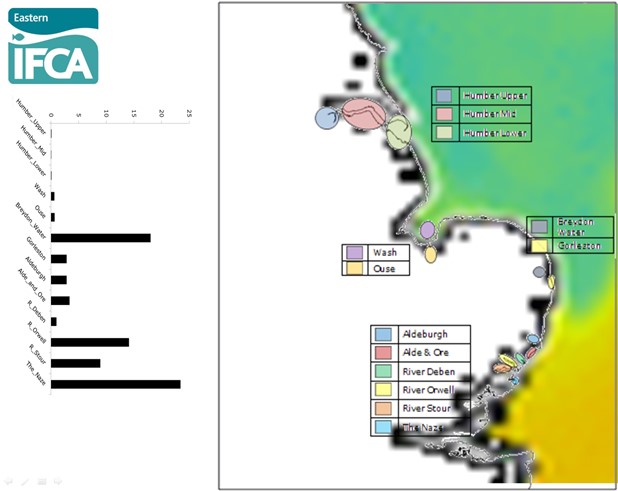

There have been various surveys of fish in estuaries, with a lot of work having been done by The Environment Agency as part of UK commitments under the Water Framework Directive. In addition, we ourselves have conducted survey work (in The Deben), and have worked together with voluntary bodies such as Norfolk Rivers Trust and Suffolk Wildlife trust.

By examining data from all of these sources, it is possible to produce a map of the abundance of bass in estuary and inshore locations within the Eastern IFCA district.

Relative Abundance of Bass in surveys at various points in Eastern IFCA district, with indication of spring sea surface temperature

This shows a general declining trend in abundance of bass – predominantly juveniles – as we move from south to north through our district, with the areas of highest abundance corresponding with those locations where winter seawater temperatures are the warmest. (The “stand out” result which bucks the trend is for Breydon Water, a large area of relatively shallow water near Great Yarmouth. It is likely that the high abundance recorded there reflects the fact that the fish surveys are done in summer / early autumn when such shallow areas will have warmed, and be very productive habitats. It may well be that bass in Breydon Water would be obliged to leave the area during spells of cold weather).

These local conditions have to be considered in the context of changes happening on a broader scale, as these can also affect the distribution and abundance of fish and other animals. The “Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership; Science Review” identified that the Southern North Sea is the sea area around the UK with the highest increase in temperature between 1984 and 2014. This has a direct effect on the distribution of “cold blooded” fish, but also has other impacts that can be far reaching.

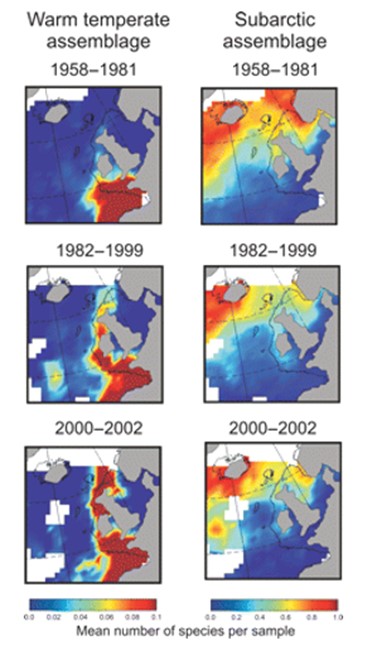

Copepods are a type of small crustacean, found sometimes in huge numbers in the plankton. They provide a crucially important food for many species of fish which are in their larval and young stage, and the abundance and timing of copepod “blooms” can determine the strength of the year class of fish. Not only is the amount of copepods important, but also the type. Different copepod species have different nutritional qualities, and fish that are adapted to feed on one type can not necessarily switch to alternative types if their optimum prey is not available. Various species of copepods tend to be found occurring in the same conditions, and these are called “assemblages”. The image below shows how the distribution of two of the very important assemblages found around the UK have changed over the last half century or so.

Changes in Copepod distribution

It will probably come as no surprise to learn that these distributions very closely follow changes in seawater temperature. But it is important to consider what this means; If a species of fish were for instance dependent on the Sub-Arctic Assemblage of copepods as food during the larval phase, then that species would at best be struggling to retain a toehold in the North Sea. And if a species were to be able to use the Warm Temperate assemblage, it would have been able to appreciably extend its distribution up the Western seaboard of the British Isles. And in fact, this is exactly what we see – with Cod and Bass respectively. Whilst there will be fisheries management considerations at play, and a direct temperature tolerance effect for each species, it cannot be denied that changes in the availability of food of the correct type in sufficient quantities at the right time of year is crucial in enabling the survival of enough fish larvae to produce good year classes.

All of the above factors are reasons why we as responsible managers of inshore natural resources need to know about the distribution of fish species, the various life stages of those species, and how these are changing over time and possibly in response to man’s activities. It is especially important to know the pattern of distribution of young fish; they are more abundant than older fish, and we can therefore pick up trends more easily than might be indicated by the random results arising from a few, scarce, older fish; they are easier to catch with simple equipment; they are often important food items for a lot of other species in the ecosystem; and they tell us a lot about both the recent history of the species (are there sufficient adults in the area to spawn effectively?) and likely future (are we seeing a good year class, and therefore likely to see a pulse of high adult abundance in future years?).

There is quite a lot of published information already available, and we have used that. The Environment Agency Water Framework Directive small fish sampling programme in UK estuaries has been particularly important. But there have always been gaps in the coverage of those surveys – for instance, The Deben estuary was not included, which is why Eastern IFCA conducted surveys there. There has also been a reduction in the programme in recent years, due to budget constraints.

This provides a great opportunity for “citizen science”, where motivated local people can make real contributions to the science needed for effective management of natural resources. The equipment and methods of sampling for small fish in estuaries and sheltered inshore waters are quite simple and straightforward. Several techniques are usually used during any particular survey, in order to capture a fully representative range of the fish species present. Nets – small seine nets pulled by hand through shallow water, dip nets used around rocks and weedy areas, and fish trap methods such as fyke nets are the mainstay. Once caught, fish are kept alive in a holding facility (sounds impressive – usually actually a children’s paddling pool), identified, counted and measured, and then returned to the sea. All the information is recorded, together with details of the sampling station and a description of local conditions. The identification of the fish is the only area where there is a need for scientific input, as it can be difficult to differentiate fish species when they are small.

We have participated in such surveys in conjunction with The Institute of Fisheries Management, and organisations such as Suffolk Wildlife Trust and the Norfolk Rivers Trust. On each occasion, there has been genuinely useful and previously unknown scientific evidence which has arisen from the surveys. Whilst a “snapshot” in time is useful, the real value of such work comes about when it can be repeated over years, and thereby pick up changes in fish populations which may indicate significant changes in natural or man made influences. Bass in large numbers are in fact relative newcomers in the North Sea, having arrived on the back of warming waters. It will be interesting to observe what other species turn up, and when. In particular, I await with interest for the first reports of the occurrence of Gilt Head Bream off East Anglia. This fish is moving eastwards along the English Channel – twenty five years ago it was a rare vagrant in the South West, now anglers in Devon can go out specifically fishing for them, with a real expectation of catching several good fish on each trip.

We would very much like to see more such surveys, and are happy to provide the technical input needed in for instance fish identification. There is a real opportunity for bodies such as the River Deben Association to arrange such surveys, and take ownership of them for the future. I hope I’ve outlined above why the information generated will be extremely useful – what I haven’t said is that the surveys are always absolutely fascinating, and great fun! It is possible for all to contribute – pulling ropes on the nets, counting and measuring fish, recording all the information, taking photographs of the area and the activities. All these take appreciable manpower, and that is something that we as a publicly funded body can struggle to have enough of. But the combination of our technical input, and the enthusiasm and commitment of all involved, can make for an interesting, productive – and usually very muddy – survey.

Let’s see if together we can find out a bit more about what’s happening on the other side of the mirror.

Illustrations, Figures and datasources

“Bass life cycle”

From a thesis “Population Dynamics of the European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in Welsh Waters” by Abi Carroll, available at http://fisheries-conservation.bangor.ac.uk/wales/documents/ThesisCARROLL_ABI_MEP_bass.pdf

Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership; Science Review

MCCIP Science Review 2017: 22 – 41 Published online July 2017. Available at http://www.mccip.org.uk/media/1750/2017arc_sciencereview_003_tem.pdf

“Changes in Copepod distribution”

From the publication “ICES J Mar Sci, Volume 65, Issue 3, April 2008, Pages 279–295”, available at https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/65/3/279/787309

Stephen Thompson

I’ve always been very interested in fish and marine life, and this led me to study Marine Biology. A deep desire to not work in an office but rather to do something practical then prompted me to work in commercial fish farming for many years. This resulted in my living and working in some beautiful, fascinating places in Europe and Asia. I’ve now brought my belief that it is possible to effectively balance the best interests of coastal communities, habitats and economies to my work in Eastern Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority – Eastern IFCA. For more information about what we do, go to our website at https://www.eastern-ifca.gov.uk, and if there is anything you want to get in touch with me or my colleagues about, contact me on [email protected].