By Julia Jones and Charles Payton

The iron hulk of the Lady Alice Kenlis, designed by the same shipwright as the Cutty Sark, has been granted protection by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) on the advice of Historic England.

The Lady Alice Kenlis was an iron steamship designed by Hercules Linton in 1867. He is the designer of the internationally renowned Cutty Sark, launched two years later in 1869. The Cutty Sark (now at Royal Museums Greenwich) was a state-of-the-art Victorian tea clipper. It was one of the fastest of its time, making the journey from Sydney to London by sail in 73 days.

The Lady Alice Kenlis is important in our understanding of early iron ships and its relationship to the Cutty Sark offers an insight into Linton’s evolution of thought. Protection by scheduling will ensure that the hulk of the ship will be protected by law. The hulk is situated on the National Trust’s Sutton Hoo estate but is not publicly accessible due to its location.

The remains of this particular ship are referred to as a ‘hulk’ rather than a shipwreck as there has been no wrecking event. Hulks are ships that have been abandoned, partially dismantled and then stripped of their fittings and permanently moored within intertidal areas, canals, estuaries and rivers.

They offered further information about protected historic sites via this link: https://historicengland.

Duncan Wilson, Chief Executive of Historic England said: ‘‘Whilst only the rather ghostly remains of the Lady Alice Kenlis survive, it deserves protection as an important part of our seafaring history. Being able to see the hulk of the ship itself emerging from the intertidal zone of the River Deben is striking and unusual.”

Arts and Heritage Minister Lord Parkinson of Whitley Bay said: “The hulk of the Lady Alice Kenlis, resting in the River Deben, offers us an important insight into the work of Hercules Linton, who – as the designer of the Cutty Sark – became one of the most notable shipwrights of the nineteenth century. I am delighted that this important piece of our national heritage has been given protected status so that it can be preserved for generations to come.”

Angus Wainwright, Archaeologist at the National Trust said: “Although we knew that the Lady Alice Kenlis was an interesting ship, we didn’t appreciate just how historically important she was. This is now our second scheduled ship at Sutton Hoo, as we also look after the site where the famous Anglo-Saxon burial ship was excavated in 1939. What’s interesting to me, is that the Sutton Hoo ship was nearly as long as its Victorian descendant, the Lady Alice Kenlis.”

Councillor Kay Yule, Cabinet Member for Planning and Coastal Management at East Suffolk Council said: “Anyone who uses the River Deben, or who has ever looked towards Sutton Hoo from the opposite quayside, will be very familiar with the sight, if not the name and history, of the Lady Alice Kenlis. She really is an established and striking feature of the landscape, so I’m thrilled that her historical significance is being recognised by Historic England with this designation. It will help to raise her profile and offer renewed protection as an important piece of our maritime past – and she becomes one of only two legally protected offshore vessels in the district, along with the wreck of an armed cargo ship off Dunwich Heath’’.

The move to list and protect the Lady Alice Kenlis was led by maritime historian Charles Payton after he had noticed her distinctive outline while visiting artist Claudia Myatt who lives nearby. Claudia helped him take a closer look and provided photographs. Former RDA Chairman Sarah Zins assisted with information about river bank ownership at that point. (You may like to refer to Sarah’s brilliant article about the complexity of River Deben ownership https://www.

I would also like to thank the editors of Topmasts and Charles’s fellow authors (including Claudia of course) for permission to reproduce that first article in full. (Topmasts, issue 40, page 10 https://snr.org.uk/wp-

Julia Jones

Revelation of a significant wreck on the River Deben

By Charles Payton

The lines of a vessel bear a close resemblance to music; they speak for what is behind them and affect the mind strongly, whether or not understood. A tiny degree of “wrong” in the sheer line is the same as musical bum note. There is another similarity. Just as the ear knows instantly the hand that wrote two or three musical compositions, with accumulations of chords and signature patterns often the same, so it is with the eye. The lines of vessels, be they ever so different in form and use, often betray the hand of the architect who conceived and drew them.

On the southern bank of the Deben in Suffolk UK, below the Sutton Hoo Estate, lies one such example, a remarkable wreck, which may have gone unregarded since it was abandoned, part broken up, in the 1930’s. Aerial photographs of it exist in Google Earth from 1945 to 2020.

On the southern bank of the Deben in Suffolk UK, below the Sutton Hoo Estate, lies one such example, a remarkable wreck, which may have gone unregarded since it was abandoned, part broken up, in the 1930’s. Aerial photographs of it exist in Google Earth from 1945 to 2020.

The wreck today before high tide © Claudia Myatt 2021

Seen from across the River, it arrests the eye by the beauty of its visible lines revealing the promise of a very fine underwater form. With its bow to the SW downstream, and its sternpost rising vertically over what remains of the propeller gland, it appears from above as an elipse, being partially dismantled to the waterline. A solidly built iron ship, what is left is substantial (about 123ft (37.5m) length and 19.18ft (5.85m) beam).

What and who is she?

Local information says it is steam dredger. Can that be correct? How do such ravishing lines and age of the 19th century add up to the word “dredger”? What genius built this to dredge? On the face of it the hull is that of a steam and sail vessel used as transport or yacht and that by no mean hand.

Initial results support the locals:-

‘…south bank of River Deben opposite Limekiln Quay, Woodbridge. Large vessel, circa 40m in length, long lenticular shape, with pointed prow and stern…. Hulk of an iron steam dredger, The Holman Sutcliffe, of circa 1890. Brought to Woodbridge by Jock Pollock, who dredged gravel from `the bar’. Broken up in the dock at Limekiln Quay in late 1920s/early 1930s’. see… https://heritage.suffolk.gov.uk/Monument/MSF17225

And another reference begins the voyage towards understanding …

‘in 1913 Bristol Sand & Gravel purchased the 1868 built, Boston registered Holman Sutcliffe and converted her to an aggregate dredger as such she traded until scrapped in 1932.’ See…http://sandsuckers.blogspot.com/2017/01/bristol-channel-trade-1912-to-1950.html

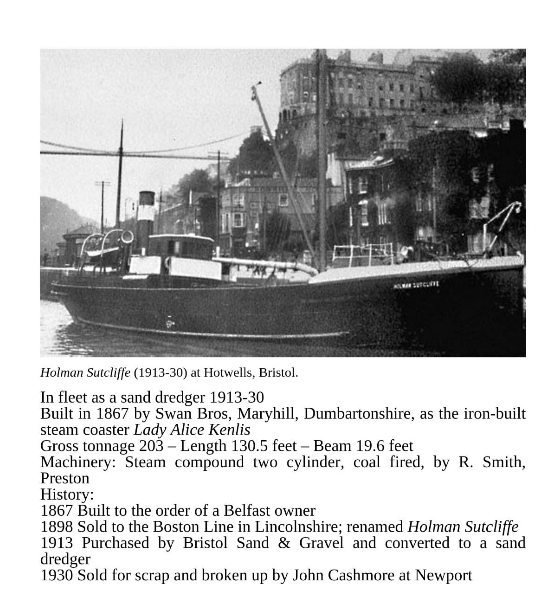

In A Century of Sand Dredging in the Bristol Channel Volume One: The English Coast, author P.Gosson, pub. Amberley 2011, she is identified as the first suction dredger at Bristol. A photograph appears of her at Hotwells, Bristol and a history is given:-

Reproduced by kind permission of Amberley Publishing

Holman Sutcliffe, steam suction dredger, converted from the steam coaster Lady Alice Kenlis of 1867, built by Swan Brothers, Maryhill, Dumbartonshire. Is fully identified at http://www.clydeships.co.uk/view.php?ref=22136

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This Clydeships recording, and her entries in Lloyds Register of Shipping, provide the final evidence that the Deben wreck was built as Lady Alice Kenlis a sail and steam screw ship, three masts, schooner rigged of dimensions closely resembling those of the wreck.

She so remained until sold to Holmans at Boston, Lincolnshire in 1908 (and maybe until 1913 when converted). She was created to trade between Belfast and ports on the Northwest coast of England and Scotland. She carried passengers and varied cargo from livestock to steel plate, as widely reported in the newspapers of the time. In 1875 she was advertised for sale in the Liverpool Mercury on the 18th October as follows:-

‘214 tons gross, 156 tons net register; built under special survey by Messrs J.R. Swan, Glasgow in December 1867 and classed *AA1 at Lloyds. Has two inverted direct acting engines of 50 horse power, by the Greenock foundry; diameter of cylinders 22 inches, length of stroke 18 inches; steams 7 ½ to 8 knots on a consumption of 7 hundredweight an hour. Is one of the strongest boats afloat having been specially built to carry heavy cargoes, and take the ground in dry harbours. It is abundantly found and quite ready for sea. Dimensions: length 123.3 feet; breadth 19.6 feet; depth 9.8 feet’.

This confirms why she could eventually wind up being converted, ignominiously, to sand dredging – she had a decent hold and particular strength, with the added advantage of being able to take the ground. This was desirable for ships dredging in the Bristol Channel, which commonly laid over on a convenient bank between tides to maximise time working. By great good fortune a painting of her as launched survives at Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, here reproduced by their kind permission:-

© Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library, Preston

This picture may also be accessed at:- https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-lady-alice-kenlis-151989/search/keyword:lady-alice-kenlis–referrer:global-search

Again the observation of her beautiful hull form comes to the fore; seen in the wreck, then as a sand dredger and now in her portrait as first built. In particular her plumb stem and fine stern echo something else; but what? She betrays the hand of a fine naval architect. Who at Swan’s yard designed her? Following up on the launch name Isabel Andrews reveals nothing. It is as Lady Alice Kenlis, that a truly astonishing answer is found.

Of National and International Importance?

Robert E. Brettle, in his book The Cutty Sark, Her Designer and Builder Hercules Linton published by W. Heffer & Sons 1969, produces evidence Hercules Linton accepted private commissions before he and William Dundas Scott formed Scott & Linton and built the Cutty Sark. Brettle (who married a grand-daughter of Linton) had at his disposal family papers

He found notes by Linton himself, and newspaper cuttings in a scrap book, stating that Linton designed and supervised the building of the Lady Alice Kenlis. The newspaper reports were highly complimentary and are comprehensively quoted, although Brettle did not know where they originated, because the cuttings were not identified. These have now been found.

Lady Alice Kenlis created an unusual stir upon arriving in the Abercorn Basin, Belfast on her maiden voyage from Ardrossan laden with 260 tons of coal. She had taken the passage in 11 hours 40 minutes against a heavy head wind and had reputedly achieved 10 knots. [the straight line distance is approx 70 nm so the alleged time may lead to a near average of 6 knots]. The report in The Belfast News-Letter – Monday 16 March 1868 describes her as of very handsome appearance and well fitted for her intended trade – traffic in cattle, goods and passengers. So far so good, but as the saying goes “there’s more”.

Linton is personally praised by Hugh Andrews Jnr. for whom the ship was built and she impresses the newspaper reporter not only by her fine lines but her build, described as of extraordinary strength, ‘similar to the gunboats of Her Majesty’s Navy’. Her plate exceeded, by one sixteenth of an inch, Lloyds Rules and:-

‘twenty tons more iron being used in the construction than specified by Lloyd’s. It is fitted with a strong box keelson, twelve inches by ten, two bilge angle irons and side girders, with double reverse bars running to the upper turn of the bilge, and reverse bars running alternately to the gunwale . . . the keel, stem and stern posts . . . larger than required by Lloyd’s rules. An important feature in the construction is the existence of two outside keels running the entire length of the flat of the floor, which will enable the vessel to take the ground with greater safety. The engines were supplied by the Greenock Foundry Company, and are built on the direct-acting condensing principle. They are nominally of 40 horse power, and are fed by two tubular boilers with two furnaces. The engine-house and boilers are secured by a strong teak-wood frame, water-tight, with skylight, which will be found very serviceable in heavy seas by protecting the fires. There is also a donkey-engine for supplying steam to the windlass, situated abaft the foremast, for the discharge of cargo and the loading of cattle and merchandise—the smoke being conveyed by pipes into the main funnel, so as not to obstruct the view of the Steersman. The ship is rigged as a fore-and-aft three masted schooner, with all the modern appliances, including a steam patent windlass for lifting [the] anchor. The three masts are of Savannah pitch pine, of one length from keel to trunk, and the compasses are of the finest description—similar to those used in the West Indian and Pacific mail steamers.’

The lines of the wreck have provoked a journey of research leading to something highly unusual. Although different, Hercules Linton’s magical clipper hull design, now at Greenwich, was preceded only two years before by his potentially fascinating vessel, now a wreck on the Deben. Still here for all to see more than 150 years later, like her famous big sister, there is something about the Lady Alice Kenlis that speaks, almost from the grave – and acknowledges Linton as exceptional. even to those of his time.

The Future

Whether she is as important as suspected is up to those with greater knowledge and authority to say. Purely as a national heritage artefact, marine or otherwise, this wreck of a once proud vessel designed and built by an acknowledged genius in Britain’s maritime history seems to be of outstanding merit. At the time of writing it may well be that no similar case exists.

It is worth celebration, may well reward further research and might contribute to further understanding the mind of Hercules Linton. It should attract national surveying and recording and deserves the attention of Royal Museums Greenwich and National Historic Ships. Above all, Lady Alice Kenlis is surely a priority candidate for the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973.

© 2021 A.C.S. and D.P. Payton

We thank Dr Pieter Van Der Merwe, Dr Eric Kently and Claudia Myatt for their kind encouragement and help in producing this article.

© Claudia Myatt 2021