By Gareth Thomas

The Church of St Mary of Grace in Aspall

Several months ago (probably almost a year but time flies by so fast!), I was asked by the editor if I would consider writing an article about the Churches of the Deben. With entirely misguided confidence I replied in the affirmative with the proviso that, due to some more immediate commitments, there might be some delay.

And ‘some delay’ there has been because, other commitments notwithstanding, there are inherent, major difficulties associated with the subject in hand.

For starters, the Deben we know and love, the raison d’être for the River Deben Association, is not the same waterway as it would have been when the majority of the churches were first sited, or built with stone; river walls have been laid, tidal surges have occurred, the climate has changed and the topography has been ‘weathered’. The geographical relationship between each of the churches and the river and its creeks will have changed, in some cases quite remarkably.

Secondly, the nature of the parish church has changed – it is no longer necessarily the hub of its community – it is no longer necessarily the only church in its community; there are, also, churches of other denominations. (Please see Table 1 to get some idea of how these changes have come about). Some churches may have functioned practically, as navigational aids or as watchtowers, or even as safe houses but, removed from the water’s edge, they could not function as such today.

The third ‘difficulty’ is that the more one enquires the more there is to enquire about and the more specialist the subject becomes. Even on the very day proposed for submission to the editor, there has been breaking news that there is archaeological evidence of a 1400-year-old Anglo-Saxon pagan/Christian temple in the Deben Valley, at Rendlesham, discovered in the course of a community archaeological dig called ‘Rendlesham revealed’.

So, you will see why my confidence was misguided – there is far more to this subject than meets the eye and there are many areas of expertise which warrant far greater input than I am able to give. Nevertheless, it is an important subject because some, if not most, of these churches provide a standing physical link, the only physical link, with the mysteries of the first millennium and the history of mediaeval times – they rank with castles, stone circles, barrows, and the findings of archaeological digs as evidence of our history and our heritage.

We are told by Adrian S Pye on the website <www.geograph> that the River Deben is approximately 33 miles long – it winds its way from its source near Debenham, past Ufford where it currently becomes tidal, past Woodbridge where the first tide-mill operated in 1170, and down to its mouth, its opening to the North Sea, at Felixstowe Ferry. A crow, making the same journey, would cover just 19 miles – so, yes, the river, internationally recognised for its wetlands, its fenland and its saltmarshes, winds.

The Ordnance Survey map shows upward of twenty-six ancient parish churches along the course of the modern Deben valley whilst older maps and LIDAR maps (please see Fig.ii for an example of a map derived from LIDAR) suggest that the number may be as high as thirty-one.

| Date | Monarch/Rulers | Event | Comment |

| 313AD | Emperor Constantine | Edict of Milan-accepting Christianity (previously polytheistic) | |

| 323AD | Christianity becomes official Roman religion | ||

| 449AD | Romano-Celtic Britain | Anglo-Saxons begin to invade Britain | Acc. Bede |

| 597AD* | Ethelbert (of Kent) | St.Augustine’s mission to the English from Pope Gregory I Ethelbert converted Raedwald (of East Anglia) converts before 605AD and uses ‘temple’ for both pagan and Christian worship |

Arrives Kent Acc. Bede |

| 793AD | First of the Viking invasions. | Lindisfarne | |

| 878AD | Alfred the Great | Viking leader, Guthrum, converts to Christianity. Foundation of St.Mary’s, Hadleigh – oldest church in Suffolk |

|

| 886AD | Alfred the Great | Alfred recognises Viking territory – Danelaw – | NW / NE / East |

| 1066 | Harold | Fends off last Viking invasion – loses battle of Hastings to William the Conqueror of Normandy (of Viking ancestry!) | |

| 1086 | William I (Conqueror) | Great Survey of England and Wales completed | Domesday Books |

| 1200-1290 | Early English Gothic architecture | ||

| 1218 | Henry III | Building of St.Stephen’s, Bures – Suffolk’s oldest extant church | |

| 1248** | “ | Foundation of Clare Priory – Suffolk’s oldest extant priory | Augustine |

| 1290-1350 | Decorated Gothic architecture | ||

| 1375-1530 | Perpendicular Gothic architecture | ||

| 15thC- | Henry VI | Start of the laying down of river walls in the River Deben | |

| 1517 | Martin Luther kick starts the Reformation. The rise of Protestantism within the established church in Europe | ||

| 1534 | Henry VIII | Henry appoints himself as head of the English Church | Start of CoE |

| 1539 | Henry VIII | Dissolution of the monasteries. Church buildings desecrated |

|

| 1570 | Elizabeth I | Elizabeth excommunicated by the Pope | |

| 1612 | First Baptist church. Early Non-conformists | ||

| 1642-46 | Oliver Cromwell | English civil war. The rise of Protestantism in CoE | Puritanism |

| 1650 | “ | George Fox founds Quakers | |

| 1662 | Charles II | Act of Uniformity – expulsion of 2000 dissenting ministers from their CoE livings- boost to Non-conformism | |

| 1689 | William III & Mary II | Toleration Act – official acceptance of Non-conformism | |

| 17thC | End of period in which river walls were laid down | R.Deben more like it is now | |

| 18thC-19thC | Sees establishment of several non-conformist denominations incl. Salvation Army (1865) | ||

| 19thC | Victoria | Industrial Revolution created sufficient wealth to allow restoration of crumbling parish churches and building of new non-conformist churches. |

From localhistories.org

* In the 6th century Christians in Wales, Cornwall, Scotland and Ireland became cut off from Rome and developed their own Celtic Church

** In the early 13th century Friars arrived in England and built friaries or priories in most towns

Table relating changes in a religious timeline to changes in the topography of the River Deben

The ‘controlling’ of the River Deben by the laying down of river walls was taking place at a time of considerable change in the religious history of England which included attempted Reformation within the Roman Catholic Church, the establishment of the English monarchy as head of the Church of England, the separation of the CoE from Rome, the dissolution of monasteries and desecration of most parish churches, excommunication of the monarchy and the rise in Non-Conformism. Just imagine the turmoil and fear experienced by the residents of the towns and villages associated with the river, not to mention the poverty and deprivation known to have been experienced by the majority.

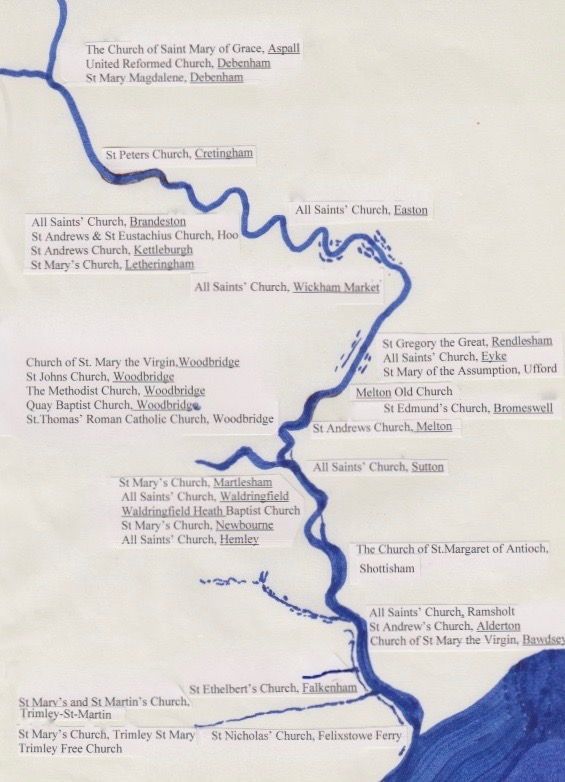

Fig. i. The number of churches which are associated with the River Deben, or which have been associated with it in the distant past totals 36. They are listed here alongside a ‘doodle’ map of the river. The possible earliest church of the Deben (the temple used by Raedwald) is not marked – the site is situated on private land not far from the Church of St Gregory the Great at Rendlesham. I have not included priories such as that in Debenham, nor have I included the Church of St Mary and St Martin at Kirton because, despite there being a namesake creek off the Deben, I can find no evidence of the village ever being close to the estuarine waters of the Deben or its creeks. I may stand corrected.

(For a bit of fun please see the footnote at the end.)

The interest of the editor in this subject may well have been sparked by the short account of Waldringfield’s All Saints’ Church in that now-well-known book entitled ‘Waldringfield, a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben’ published in 2020. The account, for which I accept responsibility, referred to the probability that stones for the building and, in particular, for the font, had been raised directly to the site from boats moored below in a creek off the River Deben. As Roy Tricker’s guide to All Saints’ informs us, the earliest window in the church dates back to 1200 AD and the font is thought to be over 600 years old; in other words these heavy stone features would have been brought to the site before the topography of the River Deben was altered by the laying down of the river walls, a process which is thought to have taken place over a period of two or three hundred years from the late 1400s.

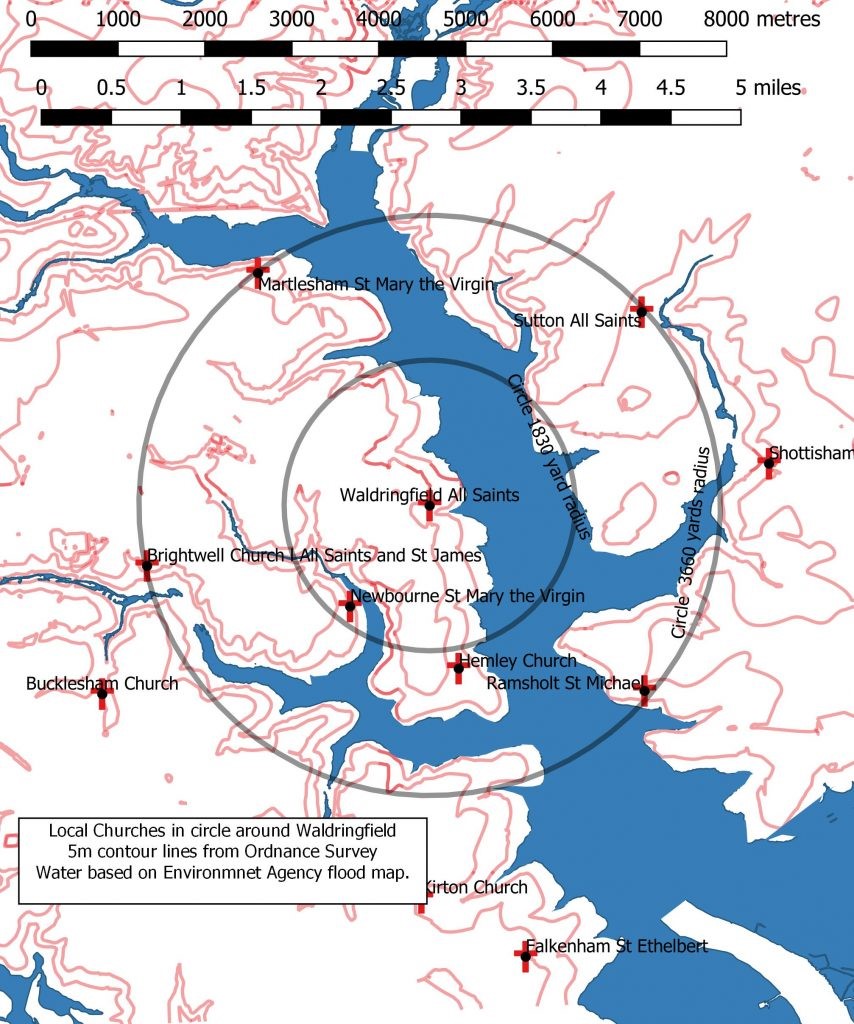

As a member of Waldringfield History Group (WHG), with access to the Group’s website, the editor may have become interested in the churches of the Deben as a result of a website post made several years ago by another member of the Group, a post entitled ‘the Ring of Churches’. The member drew attention first to W.G Arnott’s suggestion in his book ‘Place names of the Deben’ that the specific locations of churches on the Deben related to accessibility by water prior to the days of river walls. The question of access by water was particularly important as the heavy stone fonts for some of these churches were being brought from Norfolk, not down the A140, but by sea. The afore-mentioned member also brought attention in his post to an article written by David Aldred in 1999 in the River Deben Association Magazine. Aldred described ‘a circular arrangement of other churches around Waldringfield at a radius of ‘two old Suffolk miles’.

Fig. ii The Ring of Churches (as presented on WHG website)

The diagram, based on an Environment Agency Flood map, shows the geographical features of the Deben prior to the building of the river walls; it shows that Brightwell’s ‘Church of All Saints and St James’, Martlesham’s ‘Church of St Mary the Virgin’ and Sutton’s ‘All Saints’ Church’ are all exactly 3660 yards from Waldringfield’s ‘All Saints’ Church’ and that Ramsholt’s ‘Church of St Michael’ is approximately 3600 yards from Waldringfield. The parish churches of Bucklesham and Shottisham are just 500 to 750 yards outside the circle. The Newbourne ‘Church of St Mary the Virgin’ and Hemley’s ‘All Saints’ Church’ lie about 50 yards either side of the line marking a distance of 1830 yards from Waldringfield All Saints’. These churches all appear to have been built at a similar height above sea level, ie on the same contour line, but, interestingly, not at the highest point above sea level for the area. The distance of 1830 yards (or double that at 3660 yards) might not, at first, seem particularly significant but, in papers prepared for the Debenham History Society, David Aldred described 1830 yards as ‘a distance frequently noted regarding early field measurements in Suffolk’ in Saxon times.

These findings are intriguing but co-incidence is possible. One thing to be borne in mind in relation not only to this ‘ring of Churches’ but also to the study of any other parish church is that they may well have been built on pre-Christian (pagan) religious sites which might have been there for hundreds of years before the introduction of Christianity. It is unlikely that populations were converted suddenly to Christianity and that they then rejected their pre-Christian sites in favour of new sites. Instead, I suggest, it is likely that the process was gradual and sufficiently gradual to allow continued use of the religious site, first, perhaps, by building a wooden place of worship and then, as the new religion took hold, replacing the wood with stone.

But I digress from the subject matter – extant and some-no-longer-extant Churches of the Deben – not how they came to be there.

Few people know as much or more about Suffolk churches than Roy Tricker BEM so, quite naturally, I turned to him for advice. Very kindly he gave me access to his guide to Alderton Church which once had a very impressive tower, now long-since collapsed. Almost certainly that tower would have been an aid to mariners at some time in its history.

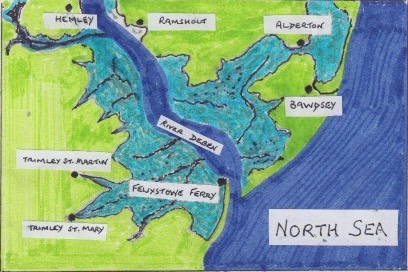

We know from the work of Peter Wain, Professor Mark Bailey and others that, at the time of Edward III, the entrance to the Deben was a busy port known as Goseford, in the area now known as Bawdsey. Alderton would have been on the north shore of that port and therefore of considerable importance to mariners with its tall tower acting as a navigation aid.. One has to presume that in those days the entrance to the Deben was easier to navigate than it is today but a relatively recent Trinity House Notice to Mariners (no. 8/15 C4) makes one mindful that it can never have been easy! It says: “Mariners are advised to exercise extreme caution when navigating in this area due to a highly mobile seabed”.

Despite the ‘highly mobile sea-bed’ the Anglo-Saxons navigated the estuary at least as far as Rendlesham. In addition, we are aware that Woodbridge was a busy port in the Middle Ages (although Peter Wain argues that it was secondary in importance to Goseford until about 1500) and that the Deben was navigable as far as Debenham, one of Suffolk’s important centres for the sheep trade. We know, also, that in the reign of Henry VIII, ships of the fleet were built in Kingsfleet, a creek of the Deben which passed from the west side of the river, past Falkenham and over toward the Trimleys (thus adding two unexpected churches to the list of ‘Churches of the Deben’ as they both pre-date the building of the river walls.

Fig. iii Goseford – a port at the mouth of the River Deben in the 15th century before the laying down of river walls. If this map were drawn in the 15th C the pale blue area would be deep blue like the North Sea and the river as it is today. Note, in particular, the Trimleys at the head of creeks and Alderton at the edge of the water. (Information for the drawing was derived from Environment Agency flood cell maps.)

There can be no doubt that some of the churches of the Deben, Alderton for instance, will have served as navigational aids, others probably not – although one has to ask in each such case whether the current physical or geographical relationship between that church and the river is as it was either when the church was built or, in the light of the foregoing discussion, when that site was first chosen as a religious site.

Throughout the world there are examples of religious edifices acting as navigational aids for mariners (Lighthouse blog). There are many examples in the United Kingdom where churches stand on high ground above the sea or estuary, viz Mawnan and the Helford River in Cornwall, and there are instances such as Morbier in Pembrokeshire in which church towers have been painted white in order to make the mariners’ lives easier.

The Thames Discovery Programme used these considerations to provide clues as to the shape of River Thames and its tributaries during the Anglo-Saxon period. The archaeologists involved in that programme concluded from the proximity to the river of many of the Thames-side churches and from the prominence of their towers and spires that ‘in addition to their religious function, the buildings could have fulfilled practical functions as well.’ – such as navigational aids and watchtowers. It is quite possible that some of the churches would have been associated with smuggling and contraband generally.

As we have seen, the subject ‘Churches of the Deben’ deepens and embeds into the mysteries of archaeology and the history of the middle-ages – it even widens into theological history when considering that there are at least five ‘Churches of the Deben’ in Woodbridge alone. The tower of St Mary’s stands high above the river; it is visible from Waldringfield and almost certainly it would have acted as a navigational aid for the barges and small ships which plied the river through the centuries. St John’s was built late in the 19th century and is not easily seen from the river, but no doubt its congregation would have included many people who worked the Deben in one way or another. The same argument applies to the Roman Catholic Church of St Thomas of Canterbury in St John’s Street, and to the Methodist Church just yards down the same street and about 400 yards from the river. The Baptist Church goes one better, being about 100 yards from the river – now known as the Church with the Hands because of the large sculpture in the church grounds, it was originally known as The Quay Church, which is a bit of a clue as to its proximity to the river!

I am sure that there are some who would like to distinguish between Parish Churches and Non-Conformist Churches and perhaps ignore one or the other, but, in reality, the only physical distinction between them is the age, and therefore the style of the buildings. The parish churches have been in place for 600 years or more, the non-conformist churches about 150 years, both much younger than the River Deben. The Oxford English Dictionary states that a church is ‘a building for public Christian worship’. It is only right and proper, therefore, to include in this survey all churches associated with the Deben, regardless of denomination.

There was mention at the start of this essay of the way in which both the river and the churches have changed. It is important to our understanding of each individual church to have some idea of the history of the Christian religion in England; this was summarised in Table I.

It is also important to have an idea of the likely topography of the river before the building of the river walls. This is best acquired by studying LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) maps. This is a mapping technique which uses scanning laser to provide considerable detail of the terrain, stripped of all vegetation. In the case of the Deben, LIDAR maps are able to show where the water was before the laying down of the river walls and where it is likely to go if a river wall is breached ie flood plains. (Fig.ii)

The first big question in this survey of Churches of the Deben is ‘which end to start?’ Should we start at the beginning of the river – at the source? Or should we start from an invader’s point of view – at the mouth? Then, how should we deal with the middle?

Maria in the Sound of Music sings that ‘the beginning’ is ‘a very good place to start’ so, at risk of antagonising the sailing and boating community, we will start at the source – no boats there, not now – not ever, I would imagine – ancient farm implements more likely.

It seems best to divide the project into three

- The sources, the concentration of the waters at Debenham, and the upper reaches as far as Hoo.

- The valley and fenland from Hoo, through Kettleburgh, Letheringham and Easton, past Wickham Market down to Ufford

- The estuarine element from Ufford to Bawdsey and Felixstowe Ferry

We are advised by Wikipedia that the source of the River Deben lies ‘west of Debenham’ to the ‘west of Ulveston Hall, near Mickfield’. Whether Debenham came before the Deben or the Deben came before Debenham has yet to be fully determined but it does seem that the name ‘Deben’ was not recorded prior to 1735 when it appeared in Kirby’s Suffolk Traveller. It seems likely, therefore, that Debenham (Old English term meaning ‘a settlement in a deep valley’) was here first, by name at least. There are no churches close to the official source which is approximately 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) north of Mickfield and 4 kilometres (2.4 miles) south of Wetheringsett. The so-called river is really a field-side brook at this point – I found it on the right-hand side of the road which passes from Mickfield to Wetheringsett; it was within sight of the Mendelsham mast which stands about a mile and a quarter to the north west.

Fig. iv Showing the brook, the official source of the River Deben, taking a right angle turn to the left (east) toward Debenham at the edge of Mickfield Meadow, the sign for which is just visible to the left of the tree on the right-hand side of the picture.

Fig. v The sign for Mickfield Meadow – A Suffolk Wildlife Trust Nature Reserve

Within forty yards, at the edge of a nature reserve known as Mickfield Meadow, the brook takes an eastward direction towards the northern end of Debenham where it will be joined by a roadside stream representing the other sources of the Deben because, yes, a second source is said to run south from the parish of Bedingfield.

I have found no evidence of exactly where in the modern parish of Bedingfield, some of the waters of the River Deben might arise. In fact, despite an innate desire to be able to include the Church of St Mary at Bedingfield (circa 1375), the churchyard of which is ‘reached by a bridge across what appears to be a stream’ (Simon Knott, writing on his website www.suffolkchurches.co.uk), I could find no cartographical evidence of any streams making their way overland to the identifiable River Deben. Of course, there is always a possibility of underground streams but who knows? – not I.

However, just two miles to the south-west of Bedingfield, in the tiny parish of Aspall there are several small field-side tributaries which join together to flow southward toward Debenham, eventually reaching the River Deben. The longest of these tributaries passes about 150 metres to the north of the Church of St.Mary of Grace, the parish church of Aspall; two other tributaries merge about 50 metres to the south of the church, then flow 300 metres to the east before joining the first. In effect the church sits in a triangle formed on two sides by tributaries and on the third side by Little London Hill. (Please see Fig.x)

It is appropriate that the first ‘Church of the Deben’ should be this one. There has been a church on this site since before 1086 when it was recorded in the Domesday Survey of that year and the Early English architecture of the chancel suggests that the current building was started in the late 13th century. The distinctive cider of Aspall is as well-known internationally as the river itself and the Chevallier family who produced the cider until recently are well tied up in the history of Suffolk.

Fig. vi The Northern aspect of the Church of St Mary of Grace in Aspall, with its many-times restored timber-framed Porch which shelters the original 14th century door. The grass is longer on the southern side!

Sadly, outside, there are signs of neglect. The churchyard had not been mown for some time and the lych-gate has disintegrated following an argument with a tree just a few years ago.

Fig. vii A sad demise – the lych-gate that was

The ‘Church of St Mary of Grace’ in Aspall epitomises the problem we have today with ancient churches, many of them listed, full of historical architecture and artefacts but almost devoid of users and, therefore, of funds; these churches depend for continued existence on a handful of voluntary devotees. It is to be hoped that this essay on the Churches of the Deben will raise awareness of this problem and, who knows, might result in a heritage trail.

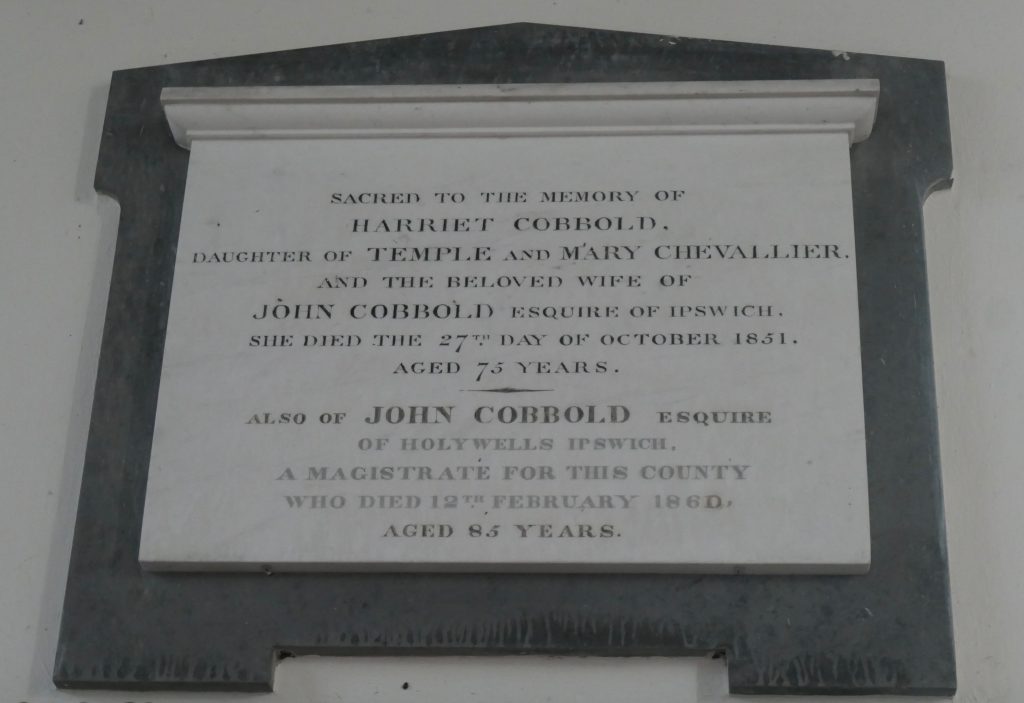

On a brighter note the interior is rather homely and welcoming with its carpeted aisle leading past intricately carved bench ends towards the chancel with its small altar and the panelled, reredos behind, texted with the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed and the Ten Commandments. One gets a real feeling of local Suffolk history when reading the floor slabs and the wall mounted plaques, mainly in memory of one Chevallier or another, but also when reading a plaque in memory of Harriet Cobbold who died in 1851. Harriet was born a Chevallier; she married John Cobbold of Holywells, thus joining together two of the most well-known Suffolk dynasties of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

There is also a memorial plaque to Field Marshall Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850 – 1916) whose mother, Frances Ann, was a Chevallier. Roy Tricker tells us in his excellent guide to the church that Kitchener and his brother drove from Aspall Hall to Mendlesham in 1903 in order to become the first passengers to travel on the Mid-Suffolk Light Railway from Mendlesham to Haughley.

Fig. viii Memorials to Lord Kitchener and to Harriet Cobbold, née Chevallier

A memorial plaque situated in a central position on the north wall of the nave strikes the visitor because, being contempory and in terracotta, it contrasts with everything else in the church. It commemorates the life of one Raulin Guild who died aged 26 in 1966; he was, in his short time, captain of the England Schoolboys Hockey XI, a Cambridge graduate and a member of the British colonial service, working in what was then Northern Rhodesia; his mother was a Chevallier – Perronelle Mary, who died in 2004 at the age of 101.

Fig. ix The contemporary memorial to Raymond Guild

The previously mentioned Deben tributaries emerging from either side of the church in Aspall are joined after 500 metres by a tributary coming from the region of Kenton Hall, well-known for its extensive moat. The tributary appears to arise as a spring between 4 and 5 hundred metres north west of the Hall, close to Bellwell Lane (evidently known in the 14th century as Knobbysyngeweye – what a lovely name for a lane or walkway!) The site of the spring is a little too far from Kenton ‘All Saints’ for that church to be included as one of the Churches of the Deben, the distance being about 2/3rds of a mile (1.1 km) but there might be a tale or two to tell – who knows?

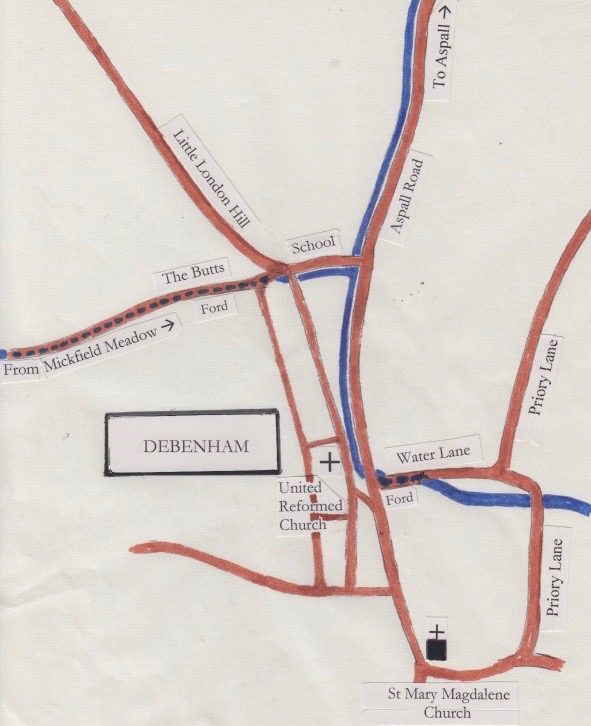

The combined waters of the Aspall tributaries follow the Aspall Road southward into Debenham. At the north end of Debenham they are joined by the waters from Mickfield which are officially denoted on Ordnance Survey and Google maps as the River Deben; these waters follow Stony Lane and The Butts into Debenham along what is referred to by Pye as the ‘longest ford in the country’ – under normal circumstances it trickles along a metalled lane over a distance of half a mile. (Please see Fig.x)

The combined Aspall and Mickfield waters flow further southward into the town centre on the other side of Chancery Lane from the Debenham United Reformed Church. There they are channelled through a culvert and under a bridge which carries the main thoroughfare to emerge in Water Lane which lies on the opposite side. Judging by its surface water, Water Lane is very aptly named. It is, in fact, another ford – just a few inches deep normally but, following Storm Babet the waters were over the top of the 6-foot depth marker.

Fig. x The River Deben and the roads of the market town of Debenham are very closely entwined. The Aspall tributary follows the Aspall Road from the top right. The Mickfield tributary forms a ford with The Butts coming in from centre left. The two tributaries join near the Sir Robert Hitcham School at the bottom of Little London Hill (which comes from the top left corner). The river then traverses the town to form a ford with Water Lane. Both churches are close to the river. (Detail derived from Google maps)

Debenham United Reformed Church, known as such since the merger of the majority of Congregational and English Presbyterian churches in 1972, was built in the early 1800s. Prior to 1972 it was a Congregational Church. The 1851 Census of Religious Worship suggests that there was an old meeting house on the site in 1788 and that a Birth and Baptisms register dates from 1706 so it is likely that some sort of religious meeting house has been there since at least the late 17th/early 18th century. Many of the buildings close to the Church will date from a similar time or even earlier. The very fact that building was possible suggests that the River Deben, passing so close to or even under the buildings, was just a stream at the time, very much as it is now. The picture postcard (Fig.xi), undated but taken when the building was called the Chapel, shows a small bridge over a stream – the Deben. However, one has to wonder whether, in the Iron Age when Debenham was first settled by the Celtic Trinovantes, it was wide and deep enough to accommodate their boats.

Fig. xi An old postcard showing The United Reformed Church in Debenham with a small footbridge over the River Deben passing from the Main Street into Chancery Lane. The hedges on either side of the bricked culvert are, today, much higher and thicker than in this picture.

Fig. xii The River Deben ambles its way down Water Lane past the six foot marker – this would have been a different picture a few weeks later at the time of Storm Babet

At the point where the River Deben traverses Water Lane it is just under 180 metres away from the north side of the Parish Church of St Mary Magdalene (Fig.xiii); it comes no nearer because its waters travel a little further east before turning in a southerly direction toward the lower end of the town.

Fig. xiii St Mary Magdalene Church, Debenham

The Church is large and impressive for the size of the town. At the western end, against the tower there is a two-storey ‘Galilee’ porch, the upper storey being a chapel. Simon Knott describes this as ‘a most unusual feature’ and Roy Tricker says in his guide to the Church that it is a rarity in English churches.

After passing the wooden stairs to the upper room of the porch one enters the ‘tower room’ through 400-year-old doors. This room, at the base of the tower, is the oldest part of the church, being of Saxon origin dating from the 11th century (Please see Fig.xiv). The upper parts of the tower are Norman. It was completed in 1380, damaged by lightning in the 1600s and restored to its former glory in 1880.

In the tower room one becomes aware of the extreme pride taken in the bell ringing which takes place here. There are plaques recording great campanological achievements and the room is lined by peal boards. The eight bells were rehung in the 1930s.

Fig. xiv Showing the outside south-west corner of the tower room and the long vertical stones interspersed with ‘shorts’ – typical of Saxon construction

Stepping down two steps into the nave one is first attracted by the red and white brick diamond-patterned flooring which is a reminder that during the 19th century Debenham boasted a brick factory. These bricks were laid in 1871. Again, one has to wonder if the river was used in any way either in the brickmaking process or in transport. Perhaps the Debenham History Association have some answers to that.

Then, looking up, there is a certain magnificence to the height of the roof and its 15th century timbers. Looking ahead there is a massive beam across the arch into the chancel. This is the rood beam which probably survived the Reformation because it clearly acts as a tie beam, keeping that part of the building together.

There are many interesting architectural features in this church – far too many to describe here. It is well worth a visit. Together with the URC described above it is an important landmark for the lovers of the River Deben. Between them they represent the small area where the Deben begins to assume its identity – no longer a field side brook or roadside stream, the river attains a position from which to assert itself.

Fig. xv The impressive diamond patterned floor in the nave of St Mary Magdalene

The Domesday Survey of 1086 is said to mention two churches in Debenham but of the other there is no sign – it has disappeared without trace from an unknown site. Roy Tricker, in his guide to Aspall Church, refers to ‘a long lost Church of Our Lady Of Grace, which is thought to have stood in Gracechurch Street’ in Debenham

In terms of ‘other churches’, it is important that we remember that early Christianity in the British Isles dates as far back as the 7th century so there is a strong likelihood of there having been some churches or religious institutions near the Deben which do not exist today. For instance, just 60 metres to the east of the point where the Deben re-emerges in Water Lane it passes under Priory Lane. We are told by David Aldred, writing for the Debenham History Association, that in the 7th century the Angles built a minster here together with a priory for the clergy. Perhaps this was the other church mentioned in the Domesday Book but, knowing the accuracy of Roy Tricker’s research, I suspect not!

Standing in Priory Lane one begins to get the feel for another important function of the Deben – irrigation. The proximity of the Deben would, almost certainly, have influenced the siting of this Priory where the mendicants would have farmed produce for their own use and for sale.

Leaving its home-town, so to speak, the River Deben turns southward to be joined by another significant tributary from the north easterly direction of Waddlegoose Lane (how I love some of these names!) and Kenton. Before leaving Debenham entirely it is joined from the west by a tributary which has followed Low Road from almost as far away as Mickfield. This is an area of Debenham, at its southernmost extreme, which is renowned for its risk of flooding despite the fact that the riverbed widens to accommodate the added waters.

The river wends its way through fenland toward Cretingham where it passes within 100 metres of the Church of St Peter, actually in Nether Cretingham as explained in the church guide, obtained through the website of the Suffolk Historic Churches Trust, from which I quote.

THE CHURCH OF SAINT PETER – CRETINGHAM

It is known from records in the Domesday Book (1086) that an Anglo-Saxon settlement existed in Cretingham, and there is little doubt that a place of worship has stood on the site of this church since then or even earlier times. It is conveniently placed above the flood plain of the river Deben, and near to a probable crossing place.

In the 12th century, the parish of Cretingham was served by two churches -All Saints in Upper Cretingham, which lay along the road to Otley, and St. Andrew’s (this one) in Nether Cretingham. In the 13th century, the living of St. Andrew’s was granted to the Canons of St.Peter’s Priory in Ipswich, which was dissolved by Cardinal Wolsey. It was not until around 1900 however that the church’s dedication was changed to St. Peter. The reason is not known.

Apart from its furnishings, this church has probably changed very little in the past four hundred years, and this gives it great charm. It never suffered from the ‘improvements’ which were so often carried out by well meaning benefactors in the nineteenth century.

There are several important observations in these few opening paragraphs of the guide but the most important from the point of view of this article is the mention of a ‘probable crossing place’. This is recognition of a serious river – not just a stream with a plank thrown across it! This is a crossing place with a proper bridge at the bottom end of Cretingham High Street – it is just the third road crossing of the Deben since it left Debenham.

Fig. xvi View of the River Deben from the bridge at Cretingham, looking east – most of this bankside foliage was flattened during Storm Babet

Fig. xvii St. Peters Church, Cretingham, looking south from the other side of the same bridge

The walls of the nave and the chancel at St Peter’s have been rendered so that it is possible for them to be colour washed. Simon Knott describes ‘ice-cream walls’ which give the building a pretty look, in-keeping with the small cottages in the village high street. The church porch is fourteenth century. The windows are all clear save for two small inserts; in the nave they are perpendicular in style and probably 14th century but in the chancel they are Early English which equates to the 13th century. (Please see Fig.xviii)

Fig. xviii The Church of St Peter at Cretingham

There is a ‘double-decker’ pulpit and the pews are box pews. The windows of clear glass allow plenty of light so that, on entering the church there is an instant air of relaxation and the feeling referred to above that nothing much has changed here since the 17th century.

Fig. xix The double decker pulpit and the box pews take the visitor back to the 17th century in St Peters Church in (Nether) Cretingham.

Everyone has different interests when visiting an historic building and, of course, it is always important to look up so as not to miss anything. An upward look at St Peter’s rewards the visitor with a view of extremely well maintained roof beams, beautiful in their symmetry and their simplicity and completely complementary to the box pews and pulpit.

Fig. xx The roof beams at St Peters – beautiful in their simplicity

After passing under the road bridge just below St. Peter’s the River Deben meanders off between the trees and across the fields in an east, south-easterly direction towards Brandeston.

Fig. xxi The Deben meanders off between the trees and across the fields toward Brandeston

A sharp left-hand bend after about half a mile takes the river south, under the Cretingham/ Brandeston road (another proper bridge), toward Friday Street which lies on the south side of the river. Just before Friday Street, where there is a former Quaker Meeting House, the river bends again – toward the east. This sets the river just behind and south of Brandeston Hall and All Saints’ Church, Brandeston and then in the general easterly direction of Kettleburgh. The ordnance survey map shows ‘fords’ and ‘weirs’ in this neck of the woods, the latter suggesting a fall in the water which might have been put to good use for milling at some time. The Domesday Book of 1086 refers not only to a church in the manor but also to a mill.

All Saints’ Church, Brandeston is approximately 1890 yards from St. Peter’s, Cretingham (plus or minus 50 yards) – strange that, bearing in mind the earlier discussion! But there is no ring of churches!

All Saints’, Brandeston is a much more formal experience for the visitor than St. Peter’s. The porch is on the north side, the side facing the road; it is approached through double wooden gates and a path lined by yew bushes.

Fig. xxii All Saints’ Church, Brandeston as seen from the road. Brandeston Hall is immediately to the right, out of the photograph.

Again, the nave and the chancel external walls have been rendered and colour-washed. The church guide confirms that the chancel dates from about 1300 and the nave and tower date from about 1370 although the features of the west front suggest completion late in the fifteenth century, about 120 years later.

Fig. xxiii The west front of All Saints’Brandeston showing the features, particularly the perpendicular tracery of the window and the door and door-arch, suggestive of a late 15thC finish

Fig. xxiv Note the fine carving on the West door and the three crowns seen on the south spandrel (to the right of the arch). These are the three crowns of the diocese of Ely, which, according to Robert Warners guide, were appropriated retrospectively to represent the ancient kingdom of East Anglia.

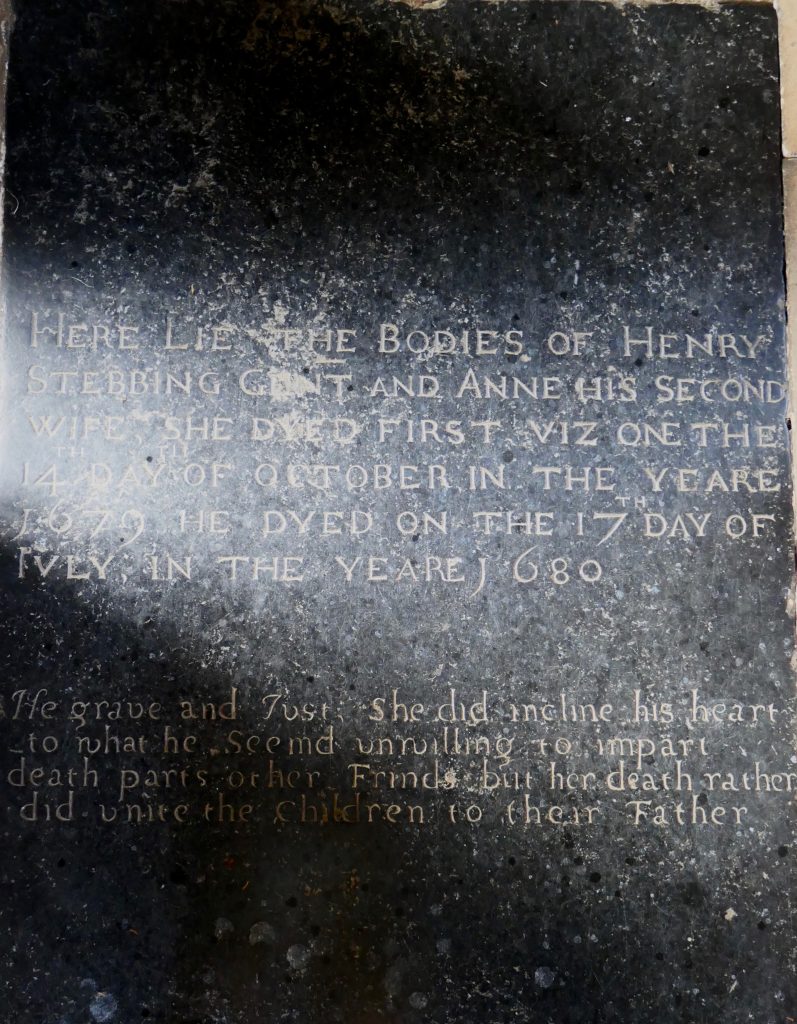

Inside, one is struck first by the light, thanks to the clear glass windows, then, almost immediately by the numerous 17th century ledger stones commemorating a small number of families – mainly Stebbings and Hawes. The afore-mentioned church guide, written by Robert Warner, includes a detailed history of the manor from the time of the Domesday Survey, a detailed account of prominent families and references to the building of Brandeston Hall in the 1540s (by one Andrew Revett of Monewden Park) and the founding of Framlingham College in the 19th century (by, amongst others, one Charles Austin, High Steward of Ipswich, who restored the Hall in 1847).

This church, like many others, was restored significantly, and probably at great expense, in the 19th century – the 1860s to be precise, when Charles Austin was Lord of the Manor. The south porch was demolished and replaced by the north porch seen in the photograph. The east window was unblocked and the lead roof of the nave was replaced with tiles. Much of the church furniture was changed.

Fig. xxv Inside All Saints’ Brandeston – note the ledger stones in the aisle and the well-preserved rood loft stairs

Fig. xxvi One of the Stebbing ledger stones taking us back to 1679 with an intriguing epitaph

He grave and Just – she did incline his heart

to what he Seemd unwilling to impart

death parts other Frinds but her death rather

did unite the children to their Father

Another striking feature was the embroidery of the kneelers – pretty well one for each space in a pew, every one different. Evidently they were ‘made between 1979 and 1984 in a grand community effort to which ‘every family in the village contributed’ to quote the very comprehensive guide.

I found no kneelers specifically indicative of the River Deben, despite its proximity to the Church. Of the 96 which appear on a website (yes, these kneelers have their own website!) two feature ships, fish and anchors but more out of a religious connotation, I imagine, than anything to do with the Deben. Many of the kneelers display themes of farming or natural history.

Fig. xxvii Examples of the kneelers

The organ, it seems, was acquired for £75 after its removal from Butley Church in 1936. It was completely stripped down in 1999 and found to have been built in 1785! It is rare and attracts organists from far and wide. The blue seems a little incongruous but was evidently used as an alternative to the painted grained wood effect which covered it before.(Please see Fig. xxviii)

The font in front of the organ is made of Purbeck marble and dates from the latter part of the 13th century ie before the present church was built – so where did that come from and how did it get here, one wonders? The marble is mined in Dorset but according to Simon Knott such fonts are not uncommon in East Suffolk and Norfolk.

On the south wall of the church there is a framed list of incumbents dating from 1306. One poor fellow, John Lowes, became vicar in 1596 and remained as such for fifty years during which time there started the English Civil War with all its religious connotations. Lowes was what one might, today, call ‘high church’ and had views which were not acceptable to the Puritans. As a consequence, he came to the attention of Matthew Hopkins, the Witchfinder General who is said to have tortured the eighty-year-old into signing a confession that he had employed two imps to sink ships at sea – which, of course, he hadn’t! In the autumn of 1646 Revd. Lowes was taken to Bury St Edmunds where, with forty innocent men, women and children, he was hanged for his beliefs. It is said that he read out the banned Anglican burial service as he was taken to the scaffold. Today he features in the Brandeston village sign, hanging from a gibbet.

Fig. xxviii The rare organ and the Purbeck marble font

On that ‘happy’ note it is time to move on but not without mentioning that in 1838 a Congregational Church was founded in Low Road, Brandeston, about half a mile from the river. It remained Independently Congregational in 1972 (ie did not join the Presbyterians and become United Reform) but it closed in 1979.

Shortly after leaving the grounds of Brandeston Hall the River Deben takes a turn in a south-easterly direction, flows for just under half a mile, then turns in a north easterly direction towards Kettleburgh thus completing a large loop, convex toward the south.

But wait! About 350 yards across the fields from the southern tip of the loop there is a parish church – the Parish Church of Hoo – the Church of St. Andrew and St.Eustachius. The origin of that double dedication is complicated. The Church lies slightly further from the small hamlet of Hoo than it does from the river so it certainly warrants inclusion in thissurvey. Simon Knott tells us that it was ‘threatened with redundancy in the 1970s’ but, linked closely with Charsfield, it has survived.

Now, I have to admit that, as yet, I have not been to Hoo or the Church of St Andrew and St Eustacius. Although the church and its 16th century red brick tower does not appear to be of any major historical importance it has achieved a degree of fame by being featured in the film ‘Akenfield’ and according to Knott it ‘has something very special about it.’ Its situation sounds very Suffolk and, let’s face it, it is close to our special river. We will start here when we examine the next set of ‘Churches of the Deben.’

Hoo, Kettleburgh, Letheringham, Easton and beyond – here we come!

Acknowledgements and a Footnote:

I am in awe of the amount of knowledge demonstrated by Roy Tricker in his various Church guides and I am grateful for his advice. I am equally in awe of Simon Knott and his ’Suffolk Churches’ website which is a fount of information and highly recommended for those interested in church architecture and history. I have used Wikipedia, Google maps and Lidar maps as sources of information and, of course, I have read and re-read the various intriguing accounts on Goseford by Peter Wain (including Proc. Suffolk Inst. Archaeol., 43 (4), 2016) and the detailed writings of David Aldred which are available on the Debenham History Society website. Robert Warner’s history and guide to All Saints, Brandeston is full of well researched historical information.

I am hopeful that there might be others with snippets of information or stories to impart on the ‘Churches of the Deben.’

As a fun footnote, provoked by a search for other rings of churches and the use of the Suffolk mile, I would refer you back to Figure 1. There are thirty-six churches listed but six were built after the development of the river walls. Consequently, there are thirty churches which pre-date the river walls. We have been informed very recently of the discovery of another – Raedwald’s Temple which the Venerable Bede implied might be used for both pagan worship and Christian worship – so we have 31 churches which pre-date the river walls. We are told that the River Deben is approximately 33 miles long which is 58080 yards but, of course, it depends how one measures a winding, wandering river, rich in fenland and wetlands. It also depends on where one starts the measurement!

Roughly speaking, then, there is very slightly less than one ancient church for every mile of the length of the modern river. Speaking less roughly but with an admitted air of mischief, it is possible to say that if the river were just 32.23 miles long (representing only a 2.3% variation from its approximate length of 33miles) then there would be an ancient church for every ‘good old Suffolk mile’ (the magic 1830 yards)

Well, it was just a thought – a bit of arithmetic fun!!

Dr Gareth Thomas MD., LL.M., FRCOG

Gareth Thomas retired as a local Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in 2010 and left the medicolegal world of Expertise in 2015. He and his wife Alison moved to Waldringfield from Rushmere Road, Ipswich in 2006, having previously lived in Nacton for nine years from 1979 – so they are getting to know the South Suffolk peninsula reasonably well! In 2007 Gareth became a founder member of the Waldringfield History Group and for ten years from 2010 he was Chairman of the Group. The end of his tenure of office coincided neatly with the publication of Waldringfield – a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben. The book was a combined effort on the part of all members of the small Group, but Gareth was one of the three members who took responsibility for the editing and management.

Never known for sitting about, Gareth may be seen around Waldringfield walking his dogs, on the water on ‘Blazer’ or crabbing with some of his younger grandchildren. He is also too well known (in his opinion) for his involvement in the village pantomimes.

For the last twenty-three years he and Alison have had a family home in the valley of the Vezere in south-west France where Gareth has been able to maintain a managed meadow and plant well over one hundred trees.