By Gareth Thomas

Part 3: From MELTON and from SUTTON to the edge of THE NORTH SEA

*This might be just ten miles of estuary but it is two banks of a wide estuary and includes the ancient maritime town of Woodbridge. Consequently, for the sake of both compilers and readers, Part 3 will be presented in two sections: 3A and 3B

Part 3A: From Sutton to The North Sea

Welcome back to those readers who have survived the first two parts of this three (now four) – part series. As I explained in part one, I had no idea that there would be so many churches in close approximation to the River Deben, either as it is now or as it was, before the building of the river walls. Conversations with others suggest that I have not been alone in my ignorance; ‘forty-odd ! – that surely cannot be’ they say, but forty-odd it will be by the time we have finished – more than one church per sinuous mile of river.

Most mornings, from our house in Waldringfield, I can see through the trees to the other side of the River Deben in the direction of Sutton Hall and then, later in the day, when walking the dogs, I look across the river and the island, and take in the whole of the eastern shore from the Rocks and Shottisham Creek to Methersgate and beyond.

Seeing the eastern shore and wondering – on a daily basis.

It always causes me to wonder what it was like when the Angles and the Saxons sailed up the river and, later, when the Vikings invaded – and, I ask, was life the same both sides of the river? And later still, when the stone churches were being constructed, did the communities on each side inter-relate and understand each other? Or were they like the French who, as late as the early eighteenth century, used their inland rivers as definitive borders and failed to understand the ‘patois’ spoken on the other side?

We can be pretty sure that our ancestors were not like the French – that there was considerable communication, certainly amongst the aristocracy, throughout both the late first millennium and the second. It is also reasonably safe to assume that the adventurous, sea-going Angles, Saxons and Vikings would not limit their activities to one side of the river – they had, after all, got here by crossing the North Sea in relatively small boats and most of us know that can be pretty hazardous.

Similar questions were going through my mind at the end of Part 2, in the churchyard at Bromeswell. That church is just one and a half miles from the mysteries of Sutton Hoo, and just over half a mile across the Deben valley from Melton Old Church, at a point where, centuries before, we would have needed a boat to pass from one side to the other. On a more personal note, it is just over four ‘crow-flight’ miles across the water from my home in Waldringfield, eight if one prefers shanks’ pony, or even the car!

Before moving on from Bromeswell I should indicate that there was, once, a Baptist Chapel in the village but it closed in 1992 and, in any case, it was situated about a mile and a half from the river, just off the Orford Road – too far to be considered as a Church of the Deben, although some of its congregation may have crossed the river daily to work in Melton or Woodbridge or, in its industrial time, Waldringfield.

With the estuarine part of the Deben valley widening quite quickly at Melton we have to decide whether to proceed with the ‘church-spotting’ down the eastern shore of the river or whether to cross to Melton and proceed to Woodbridge and beyond on the western banks.

More of the mysterious eastern shore from Waldringfield

I am inclined in the first instance to continue from Bromeswell, into Sutton and on to Shottisham as the three seem to be ‘joined at the hip’. The parish of Sutton extends over a distance of 3.5 miles from the edge of Bromswell Heath (yes, spelt without an ‘e’ on the Ordnance Survey map) to the banks of Shottisham Creek, and in so doing it presents nearly five miles of curving eastern shoreline to the Deben. W.G Arnott devotes an entire chapter of his book, Suffolk Estuary, to Sutton which he describes fondly as a ‘straggling heathland parish’ with ‘an air of hiding something, as though it is fast asleep with some great secret buried within it’ (in addition to the discovery already made at Sutton Haugh!)

The 2½ miles between St Edmund’s at Bromeswell and All Saints’ at Sutton is almost double the ‘inter-church’ distances we have experienced up river but, of course, there is a whole lot of ‘stuff’ going on to the west of us as we progress. First, there is the 7th century Royal Saxon burial site at Sutton Hoo; then, across the water in the ‘metropolis’ of Woodbridge, there are five churches and a Salvation Army within half a mile of the water and one modern church just over ¾ mile from the quay, not to mention the site of a Priory which suffered at the time of Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. We will return to those later.

The Church of All Saints, Sutton – hidden by its yews

All Saints’, Sutton is easily missed by the passer-by as it has no tower to advertise its presence. We are told by the church website that the tower, which stood in the position of the current porch, collapsed in 1642 having been seriously weakened by fire in 1616. We are told, also, that ‘one and a half churches are recorded in the Sutton entry of the Domesday Book’, that ‘the ground where the present church stands may have been considered sacred long before’ and that there is evidence of ‘a mid-Saxon settlement near the church’.

There is a diagram in W.G’s book, derived from a map drawn in 1625 by William Hayward, which shows Sutton Church, next to the site of Sutton Manor House, as the meeting point of at least ten ‘Wayes’ or sheepwalks, some radiating inland but others radiating toward the river at Ferry House opposite Woodbridge, at Mathers Gate (Methersgate), at Stonards (Stonner Point) and at Seburgh (?? Shottisham; an assumption based purely on its position on the map, although I have found no evidence of the name and I have failed to locate a copy of the map). It is likely, therefore, that Sutton itself was not only an important part of the Anglo-Saxon scene but also thriving and prosperous during the Middle Ages, when the rearing of sheep was highly profitable. The Church is likely to have been well endowed.

The Church of All Saints, Sutton – the tower once stood where the porch is now

The church is situated about 0.9 mile from the edge of the Deben, so some distance from the water but, of course, for centuries it has served a community whose estates and farms include the edge of the river from Ferry Cliff to the north, through Haddon Hall, Methersgate Hall and Sutton Hall to Pettistree Hall and Wood Hall in the south. Near Sutton Hall is Stonner Point which once provided a jetty for the loading and unloading of barges and small ships, and a ferry which would take workers over to Waldringfield where coprolite mining and cement manufacture respectively provided employment in the later part of the 19th century. There is no question, then, that Sutton All Saints’ is a church of the Deben.

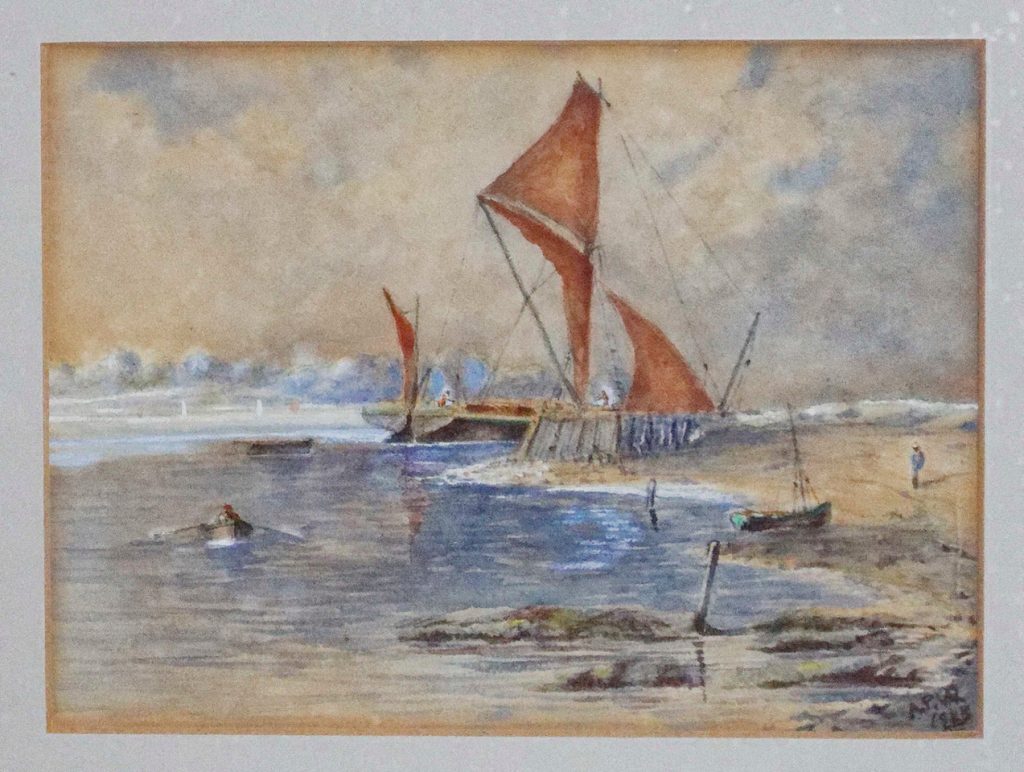

Sailing barge at Stonner Point quay – painted by Rev. Arthur Pretyman Waller in 1933

The entire medieval building was restored between 1854 and 1876, including the renewing of timbers in the roof of the nave, restoration of window tracery, provision of a new reredos (panelling behind the altar) and porch, and renewal of the east window. The tower was never rebuilt – remnants of its stair were found when the nave was re-roofed. In 1999 a timber belfry was erected in the churchyard to accommodate the single bell which had been silent for many years.

All Saints’– sensitively restored in the late 19th century and supplemented in 1999 with an outside belfry.

In the hurricane of 1987, the east window was sucked out as a tree fell on the nave roof so that further restoration was required.

The rood steps survive in the wall by the chancel arch. Also surviving is a greatly admired, octagonal, intricately carved font which dates from the 15th century, although Arthur Mee, writing in the 1940s, refers to it having been mutilated, like many others at the hands of the icon-hating Puritans in the 17th century.

The base of the rood steps – the exit from the top of the steps is better seen in a photograph of the nicely appointed nave and chancel, just to the left of the chancel arch.

All Saints’ nave and chancel

On the west wall, almost hidden in a corner complete with cobwebs is a plaque in memory of one William Burwell who died on the 23rd March 1596, aged 80. The plaque, which was almost certainly in the floor of the original nave, survived a fire in 1616.

Outside there are many yews some of which part hide the church from view when looking from the church gate. Close to the bell tower is a sad, small grave in which a child, H.K. was buried in 1794.

To the memory of a toddler – H.K. who died in 1794 – Sutton churchyard

Toward the north-east corner of the churchyard there is a memorial to Mrs Pretty on whose land Basil Brown discovered the Royal Saxon burial ground, Sutton Hoo, in 1939.

Leaving the church lane, I stopped to watch a sparrow-hawk marking its prey and hovering over the corner of the field opposite; it made a welcome alternative to church-spotting!

Amongst the houses and cottages which line the road from Sutton to Shottisham there is one which carries a distinct look of a converted chapel. I won’t include a photograph because it is now somebody’s home, but it sits there in line with several other houses, easily missed but, once spotted, distinguishable by its symmetrical front wall, its vertical ecclesiastical windows and a tiny concrete plaque in the apex, which reads ‘Baptist Chapel’.

This led me to make further enquiries and I found on Genuki that there was, indeed, a Baptist Chapel in Sutton, with a graveyard, situated approximately 1.5 miles from the river, I think in an area called Saxons Bottom, accessible now only on foot or farm vehicle. It was said to have been founded in 1813, although the National Archives have records of births dating from 1802. By 1953 it was closed, the congregation locating to ‘a church on Main Road’. Wikipedia confirms the existence of a ‘small Baptist church, called the Chapel, located on Main Road’ and says that it was founded in 1813. That building would be the same distance from the river as All Saints’ and, almost certainly, members of its congregation would have been involved in local employment including the Cement factory in Waldringfield; so, yes, a Church of the Deben.

On either side of the road into Shottisham there are fields with bulrushes suggestive of wetland and indicative of there having been a wide riverbed before the river walls were built. This would have been Shottisham Creek which flowed close to the Church of St Margaret of Antioch. It also flowed close to the Sorrel Horse which is separated from the church by just a few cottages and a flight of steps up from the lane to the churchyard.

Churchyard steps at Shottisham with the rectory gate to the left.

But where is the church? It is there – behind the Spring foliage.

The village website informs us that the church was built in 1313 under the auspices of Butley Priory and that there was a church there before that time which is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. Arthur Mee, in his Kings England: Suffolk states categorically that the font and the priest’s doorway predate the nave and the chancel i.e. they predate 1313.

The octagonal font is indeed 13th century (Early English 1180 – 1275) and is made of Purbeck marble.

The tower is Perpendicular in style and dates from the 15th century. In the spring and summer one is hard pressed to see it through the fresh foliage of the trees which line the steps up to the churchyard. But it is there, I can assure you, in all its medieval glory, but re-topped, complete with gargoyles, in 1867 when the church was restored and ‘north-winged’ by local architect Edward Hakewill. The Angels & Pinnacles website informs us that the east window was glazed by stained glass specialists Ward and Hughes shortly after the Hakewill renovations. It is unusual for an east window, being composed of three separate tall lancets but it is also rather beautiful, complemented as it is by the sculptured round window above. Ward and Hughes were London based and exported stained glass all over the world. In the 1870s they were associated with the ‘Aesthetic Movement’ which promoted pure beauty in art and architecture. I would say that this east window at Shottisham is an early example of their Aesthetic work.

The nave and chancel at the Church of St Margaret of Antioch. Note, particularly, the east window and, in the south wall of the nave (right side!), partly obliterated at their base by Christmas foliage, the rood steps.

Note also the beautiful candelabra.

Both the nave and the chancel were built in the 14th century. The floor is made of simple Suffolk bricks. Close to the chancel there is a small brass plaque in memory of Rose Glover who died in 1612. She was the wife of the then Rector. Alongside a sunflower and a rose there is an inscription which reads

As wither’d rose its fragrant sent retains , so beinge dead, her virtue still remains.

Shee is not dead, but chang’d. The good ne’r dies, but rather shee is Sun-like, sett to rise.

Ancient (brass plaque dated 1612) and Modern[-ish] (carpet).

The Britain Express website, always good for added historical information and excellent photographs, says of the Rector that his grief, thus expressed, ‘did not stop him from remarrying and fathering a dozen children’.

Also in the floor near the chancel step was a stone marking the intriguing ‘entrance to vault of Rev.W.Kett’ who was Rector at Shottisham in the 18th century.

Victorian beams designed by Hakewill

You might think from these observations that, at Shottisham, I did nothing but look down but I also looked up, as I always do, to take in the fine Victorian beam-work and the candelabra.

Outside, from the southern part of the churchyard, the tower is easily visible – so, yes, it is there. Also from the churchyard, on a good day, one can just see the Deben, just as one might get a fleeting glimpse of the tower when sailing up the Deben. I doubt if this tower was ever used as a navigation aid but the top of the tower would always be useful for look-out purposes.

The tower and south porch at Shottisham

On the village website it is suggested that the workers who built the church stayed at the Sorrel Horse Inn which would suggest that the pub, or, more likely its predecessor, may be older than the original church. It is now owned by the Shottisham community and has a good reputation for its standard of food.

Talking of communities, there is another place of worship at the far end of Church Lane where the road fizzles into a track; called ‘The Place by the Water’, it is part of the Lightwave Community which is, to quote their website, a ‘Bishop’s Mission Order under the Bishop of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich in the Church of England.’ It aims to be Church for people who don’t normally “do church”. There is a Board of Trustees which includes the Bishop of Dunwich. The building has the appearance of a modern house, but it is obviously an officially recognised Christian retreat, unmarked as such on the 2015 Ordnance Survey map but clearly marked as a place of worship on Google Maps. It is 1.5 miles from the River Deben which is the same distance from the river as St Margaret’s but, of course, St Margaret’s was built beside a significant working creek before the river walls were built whereas, today, the ‘water’ that the ‘Place’ is ‘by’ is not immediately obvious, except, perhaps, at times of flooding. Bit of a ‘VAR’ decision as to whether or not it is a Church of the Deben but because of its name and because it seems to represent a full circle from the days of Priories and the like, I thought I would include it.

Less than a mile south of Shottisham, just after Shottisham Hall there is a poorly signed turning to the right indicating the road to Ramsholt Church. The proverbial crow would have to fly just under two miles from one church to the other but the horseless carriage has to cover about 2¾ to what is now a remote spot – many of the houses which once formed the hamlet of Ramsholt have been demolished, simply because of wear and tear. Where they once stood there are ploughed fields.

I originally had it in mind to finish this third and last part of ‘Churches of the Deben’ with All Saints’, Ramsholt as it has an antiquity and magic of its own. It is, after all, the first sign of safe-haven for those mariners who have fought the elements of the North Sea and the mischievous shiftiness of the river entrance, not to mention the grounding threat of the unmarked Horse Sands. After all that, the round tower of Ramsholt imbues an air of relaxation and I think Robert Moore’s simple oil, dated about 1880, conveys just that. Despite that, I have decided, now that we are in the atmosphere of this real old-world part of Suffolk, we will continue our exploration of the Deben’s churches as far as the North Sea, then return inland and explore the western shore.

The Church of All Saints at Ramsholt in the late 19th century by Robert Moore

There are other artistic depictions and photographs of Ramsholt Church in Robert Simper’s book entitled ‘The Lost Village of Ramsholt’ published in 2020. One in particular shows its state of decrepitude in the late 18th century when Ramsholt ‘lacked a good squire’ capable of paying for repairs.

Although All Saints’ Church at Ramsholt is probably the oldest existing building of all our ‘Churches of the Deben’ it is not mentioned in the Domesday survey. In the church guide Roy Tricker explains that the Survey was a list of what people owned in the parish rather than a list of its buildings. Consequently, the absence of a Church in the Survey does not necessarily mean that there was no church in existence in the parish at that time.

The Church is an imposing sight which, today, blends with its natural surroundings, but in medieval times it probably stood out from them much more clearly as a navigational aid. Robert Simper’s book includes a photograph of the flooded marsh in 2013 which gives a good impression of what it might have been like in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Not the most brilliant of photographs, composition-wise, but it shows the 13th century windows and priests’ doorway of the chancel on the right and provides a comparison with the Decorated-period tracery of the window in the south wall on the left. It also shows, in a line, five 18th century Waller headstones, of which more perhaps when we discuss Waldringfield, across the water. The simple memorial stone to the left of the nave window commemorates Captain Joe Clark of whom I have written in this Journal in the past. A Captain in the Merchant Navy, he married into the Waller family, he was a much-loved friend to many ‘Debenisters’and he was the co-founder of the Waldringfield History Group.

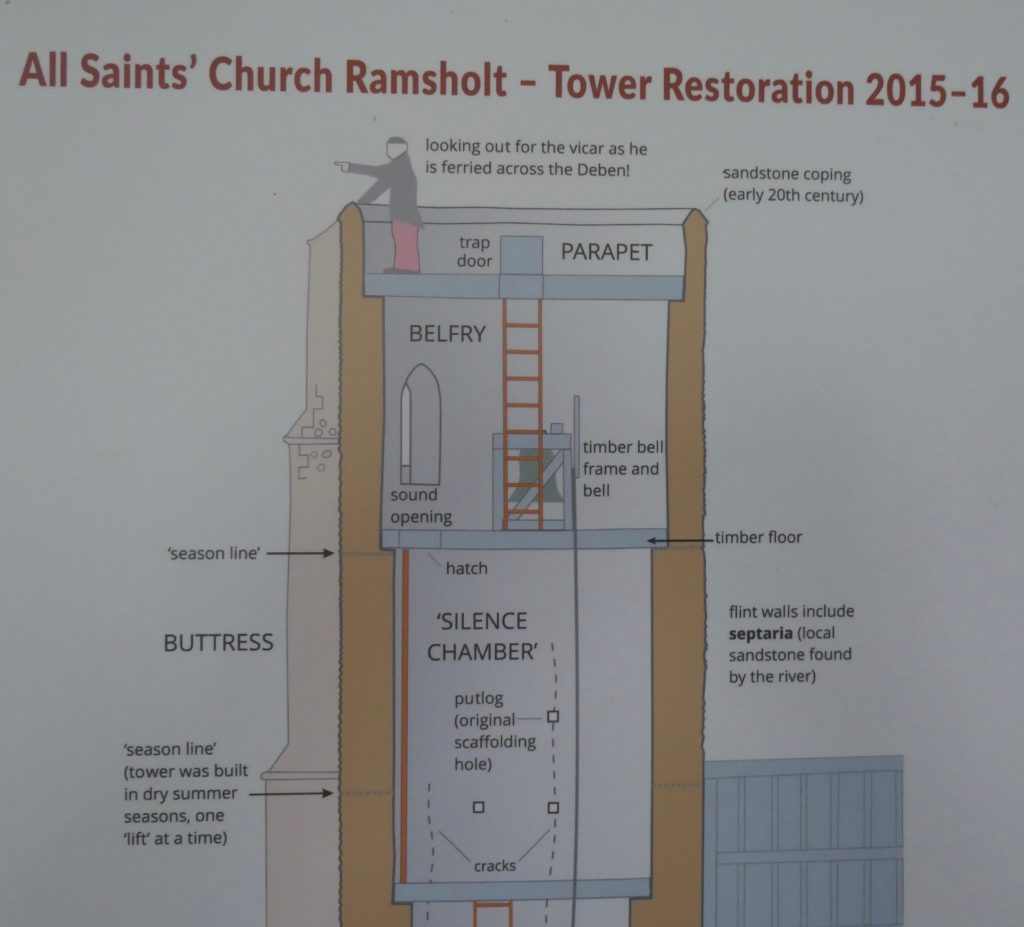

The tower is one of only 181 round towers in the country and, of these, all but 13 are in East Anglia. For more information about the tower, we are able to turn to the website shct.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ramsholt-tower-board-by-arthouse.pdf where we learn that, although there was a Saxon settlement at Ramsholt as early as the 7th century and although local legend says that the Saxons built the tower as a watch tower to guard against the Vikings, the original tower was probably built by the Normans, also, perhaps, for look-out purposes. It is likely that the present tower, with its buttresses, was a rebuild, in the late 13th/early 14th centuries, following collapse of the original. Doubt is often raised as to whether the tower is round or oval but aerial pictures show definitely that it is round; the apparent oval shape is an illusion created by the three buttresses which support it.

The ‘tower’ website is all-encompassing with its information. We learn that the tower was built in stages, that building was limited to the dry summer months and that only one stage would be built each summer – a four-year job, then?! We also learn that it was built round, rather than square, for increased stability on light, sandy soil, especially when the building material was mainly a mix of relatively small stones. This construction policy probably accounts for the high number of round towers in East Anglia.

The website carries the first official reference to smuggling which I have seen (in relation to Churches of the Deben), explaining that in the early part of the 18th century, smugglers would use the tower as a look-out to check out when the coast was clear to bring in the contraband for storage either in a cave in the cliff or in a nearby cottage.

An optical illusion. The oval-looking, but absolutely-round tower from the south-west churchyard gate

Sadly, the condition of the church and tower deteriorated through the 18th and early 19th centuries and daylight became visible through the church ceiling. The interior was described as ‘neglected’ and by 1850 the pulpit was barely usable as it had been ‘selected by an owl as a place of repose’!

Corrective measures were taken by the Churchwarden J. Pretyman so that, in 1851 at the time of the national religious census, the church was described as being ‘in good repair’. Shortly after, in 1854, Ramsholt acquired a priest of its own, the Reverend Henry Canham, who lived in Waldringfield and commuted by rowing-boat. The tower was used as a look-out by the verger or his delegate and once the reverend gentleman was espied approaching down river, the tip would be given to the bell ringer to ring the bell and summon the congregation. At times of inclement weather there would be no sighting, no bell, no congregation and no service.

Reverend Canham was at Ramsholt for 24 years. He spearheaded much of the restoration which took place in the second half of the 19th century. Many churches were refurbished at this time, usually in ways which tended to return them to a pre-Reformation layout but Ramsholt took a different course. It chose, instead, to keep a post Reformation character: the church was furnished with box pews in which those nearest the chancel faced the pulpit rather than the altar and the pulpit itself continued to be three tier. The upper tier was for the priest to sermonise, the lower lectern was for the readings and then one of the pews provided a lectern for the clerk who would announce hymns, read notices and, to quote Roy Tricker, keep order!

New mid 19th century box-pews provided draft excluders at the back, pulpit-facing seating and a triple deck pulpit, the lowermost deck being almost indistinguishable from the pews but providing a small desk for the clerk. Note the Norman tower arch at the west end, just behind the font and to the left of a copy of the information given on the tower website.

Further restoration took place in 1913 under the direction of the Quilter trustees, the Quilter family being the local landowners and the occupants of Bawdsey Manor since 1883.

Information from the website

More restoration was required in the 1970s and 1980s and in 2015 extensive restoration of the tower was financed not only by individuals and charitable trusts but also by The Round Tower Society, Suffolk Historic Churches Trust and a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, such is the importance of this iconic building.

The floor is composed of simple Suffolk bricks, warm in texture. There are several interesting features including a stone coffin retrieved from near the base of the tower in 1850; this probably dates from the early 1200s and it is likely to have accommodated a Butley priest, post mortem of course! In the north wall there are two high-up small windows, probably Tudor like the triple window near the porch. These are best appreciated from outside.

The likely last resting place of a Butley priest

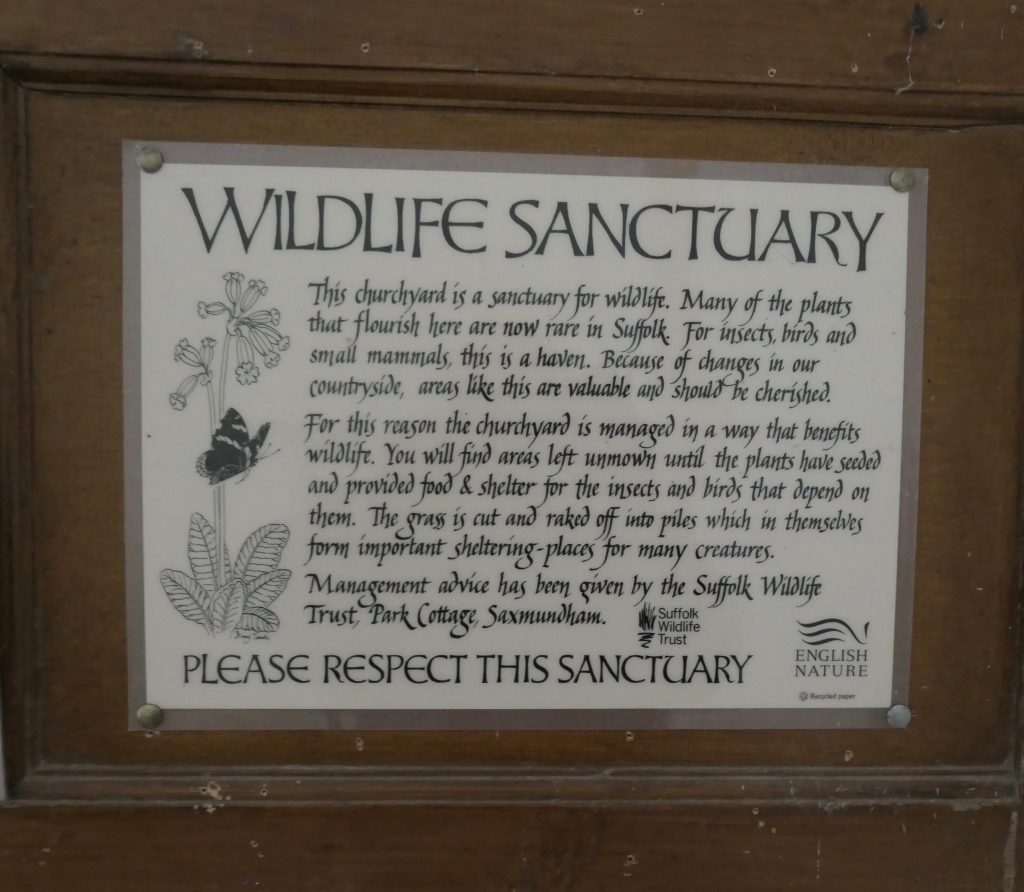

I have studiously avoided saying much about churchyards but All Saints’ at Ramsholt is worthy of further commentary for reasons described in a notice inside the church door – it is managed primarily in favour of wild-life so that there is less grass cutting than in many churchyards but there are a whole lot more wild-flowers and all the fauna that goes with them. The view from the churchyard inspires awe. Having entered through a gate at the south-west corner, one exits with a great sense of peace through the main gate at the north-east corner.

Sanctuary for all

There are two more churches to visit before we reach the North Sea.

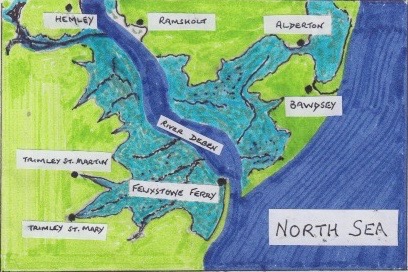

St. Andrews Church at ALDERTON is approximately 2¼ miles from the River Deben and only 1¼ miles from the North Sea. However, it was not always thus. We know from the work of Peter Wain and others, including Professor Mark Bailey, that in the fourteenth century, when Edward Third was at war with France, there was a vast expanse of water, the port of Goseford, just inside the entrance to the Deben. It extended from Bawdsey, then an island, in the east, to Falkenham and Gulpher in the west with tributaries extending to the Trimleys and Kirton. Ramsholt Church would have stood on a headland marking the entrance to the narrower upper reaches of the River Deben. A ‘doodle-map’ which I included in Part 1 of the series will serve to remind us of the topography at that time, before any river walls were built.

Goseford – a port at the mouth of the River Deben in the 15th century before the laying down of river walls. If this map were drawn in the 15th C the pale blue area would be deep blue like the North Sea and the river as it is today. Note, in particular, the Trimleys at the head of creeks and Alderton at the edge of the water. Missing from this rather rudimentary map is Walton – at the head of the inlet below the ‘L’ of ‘Felixstowe Ferry’. (Information for the drawing was derived from Environment Agency flood cell maps.)

Both Alderton and Bawdsey were port towns with the churches situated not far from the water. They remained as such until the building of river walls and the reclamation of marshland. Looking at St Andrews across the field from the south, just imagining the field as water,one gets the picture. I am reminded of a similarly aged church in St Anthony in Meneage on the Helford River in Cornwall where I spent most of my holidays of childhood and early adulthood. We have two paintings of St Anthony on the wall of our stairwell at home; they are completely different in style but they both show the church standing parallel with the shoreline, no more than thirty feet from the beach with its fishing smacks and row-boats. I imagine that, in its time, St Andrews at Alderton was much the same – perhaps just a little higher above the water level. The church lies on the 5m contour line.

The Church of St Andrew, Alderton across the fields from the south. The whole of the south wall of the nave (seen here) and the whole of the chancel (also seen here) were replaced in Victorian times.

The Domesday book records the presence of a church in Alderton but the existing nave was not built until the early fourteenth century as suggested by the Decorated style of the north doorway, which is original, and the style of the windows. It is likely that the chancel was built at about the same time, but the current version is a Victorian replacement; the original was demolished about the turn of the 16th/17th centuries by which time much of the recorded finery of the church had been removed during the Reformation.

The 15th century north porch

The north porch and the tower, both original, have features characteristic of the 15th century, in particular the Perpendicular-style west doorway of the tower. Despite its thick walls the future of the tower was to be chequered mainly because of the building material used for infill, namely local septaria. In November 1821, during an afternoon service and a simultaneous gale, the already ruinous steeple tumbled to the ground, falling, fortunately, to the west so that there were no human injuries. Roy Tricker tells us in his guide that the only casualty was a cow grazing in the churchyard, but also that several ships foundered off the Suffolk coast in that same gale.

The tower today. You have to look very carefully. Through the sycamores it is just possible to see the top of the Perpendicular style west doorway, the frieze above it and, above that, the massive western tower arch. The tower arch inside the nave gives a better impression of the grand scale.

The tower was reduced and repaired in 1865 but by 1959 it was causing concern again and, today, it is surrounded by fencing and signs warning of the danger of getting too close. The church bell hangs close to the fence.

The Church bell, outside, in front of the tower

When I arrived at the church, on a Saturday, there were two cars parked up close; ‘probably doing the flowers’, I thought. I passed through the 15th century porch with its intricate but worn flint flushwork before gently opening the door and realising that there was a gathering of people within. Most of them, including children, were in the chancel but one gentleman in the massive nave, when I asked if I was intruding, explained that they were there, out from London, to spread his father’s ashes – he had been a longstanding resident of Alderton. He was happy for me to stay but I was hesitant, so I took a quick glance at the very high and impressive, Perpendicular-style arches at each end of the nave, and I observed the Royal Arms of George III above the chancel arch. There can be no doubt that when this church was originally built it was designed to impress but, of course, it was the parish church of a community heavily involved in international trade, and it was catholic.

The tower arch at the west end of the nave gives a better idea of the immense scale of this church

My attention was drawn to metal grilles in the floor of the nave. These not only represent the heating system but also a series of tunnels running between Alderton Hall to the west and the Swan Inn to the east. Inevitably smuggling here was rife from at least the sixteenth century but, before that, escape tunnels and hiding places had been required at the time of the Reformation to provide safety for catholic priests.

I missed a lot of inside detail, I am sure, but I made good my escape and as I left the churchyard, the bell, cast in 1740, was tolling for one of its dear departed. I made my way, above ground from the porch to the east wall, stopping to notice an intriguing brick archway at ground level: the entrance to the vault of one Samuel Cross. I wonder if his vault links with all the tunnels or whether, at one time, there were steps down from the ground here.

An entrance in the east wall to the vault of one Samuel Cross

And so, to the village of Bawdsey.

The Church of St Mary the Virgin in the longitudinal village of Bawdsey is situated on the main street through the village, on the west side, toward the southern end. As with Alderton, the church is now situated over 2 miles from the River Deben, but it is less than a mile from Hollesley Bay and the North Sea.

First impressions from any angle are of a striking but stunted, square tower. Stunted because, like Alderton, this tower has a tale to tell. It was built in the 15th century. Authorities seem to differ over the proportion of the original height which has been lost, whether it is a third or two thirds. Whichever, judging by the immensity and strength of the base, it was a very impressive structure when it was first built.

St Mary the Virgin from the road. The impression from any direction is of an impressive but stunted tower. Close inspection of the east wall of the tower shows the apex of a one-higher church roof.

Entrance to the church is via the west door in the base of the tower. The room is very dark but with the door ajar one can see a staircase to the left providing access to the organ loft. The organ was built by Joseph Hart of Redgrave, North Suffolk, probably in the second or third decade of the 19th century. It is said that there is only one other, similar organ and that is somewhere in Wales. Even this one at Bawdsey has travelled – but not far; it is possible to access a gazetteer of church organs in Suffolk via the remarkable Suffolk Churches website; there David Drinkell, the organist at the Cathedral of St John the Baptist, St. John’s, Newfoundland, informs us that the organ came from Shottisham sometime prior to the 1930s. I mention all this because it just shows how small is the world and how fantastic the world-wide web can be. Anyway, this organ was restored to its original state by Ipswich-based organist and organ builder, Peter Bumstead, in 1984.

I imagine the organ has played not only hymns but also many marches because St Mary’s became a Royal Airforce Church when the RAF were based at Bawdsey Manor between 1939 and 1985. At the foot of the organ-loft stairs there is a board which lists the Commanding Officers throughout that time and many of those names could tell a story or two.

Access is via the west door in the base of the tower

Note the infilling of the aisle arches, the preservation of the original arch pillars and the bricking up of the clerestory

On the opposite side of the tower room to the stairs, I located a laminated information sheet which sums up St. Mary’s chequered history very succinctly, but incompletely – it reads as follows:

Bawdsey has long possessed a church. There is record of one in the Domesday Book of 1085(sic)

It was once a magnificent building with a high tower, a wide nave with side aisles and large chancel which is thought to date back to 1210. Now only the tower and nave remain.

In 1841 on November 5th a fire thought to have been started by young lads playing about with fireworks gutted the roof and the upper stages of the tower had to be dismantled. The restoration was completed in 1874.

What is not mentioned in this history is the effect of the Reformation in the 16th century and the effect of Puritanism in the middle of the 17th century. This proud building, linked closely to Butley Priory which supplied its clergy, would have been stripped of much of its catholic grandeur in the Reformation and any remaining icons would have been defaced or removed on the orders of ‘Smasher’ Dowsing in his role as ‘Commissioner for the destruction of monuments of idolatry and superstition’.

Also not mentioned but provided by Simon Knott in his Suffolk Churches website is the decision in the early 19th century to reroof the church with thatch, supposedly because ‘bits’ kept falling off the tower, resulting in damage to the tiled roof of the nave. That decision, of course, proved fatal some twenty years later when the whole lot went up in flames.

Both aisles were demolished and the arches were in-filled with whatever stone was available leaving the pillars exposed. The clerestory (the upper part of a north or south church wall, usually with a series of small windows) on each side was bricked up. Simon Knott tells us that the outside walls were once rendered, which may have looked neater but would have covered an immense amount of history.

Perhaps one of the greatest treasures in this parish church of Bawdsey is the piece of embroidery, framed and glass fronted in the shadows on the south wall. Possibly originating as a mediaeval bishop’s cape or cope, it was set on a background of brown velvet in the 19th century and made into an altar frontal. It was given to the church by the Quilters of Bawdsey Manor who are thought to have brought it back from Belgium. It is believed to have come from the chapel at the Manor (would that be another Church of the Deben?).

The beautiful panelled altar frontal proved impossible to photograph owing to reflection from the covering glass but David Ross provides a good photograph at Britain Express.

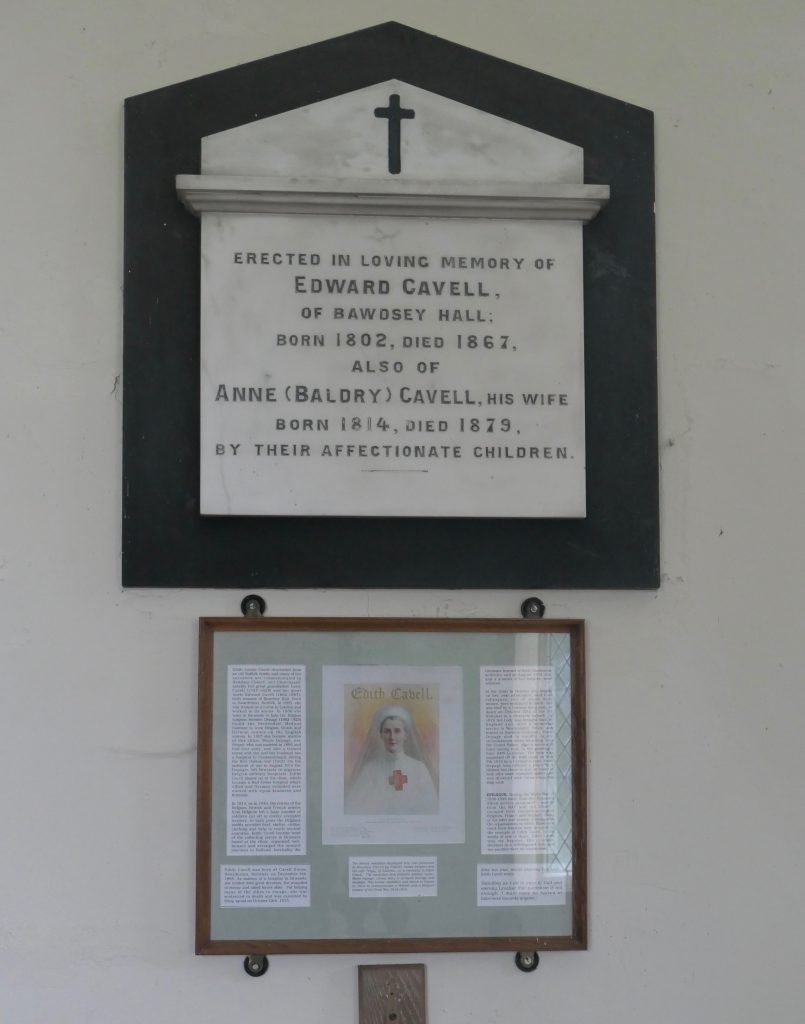

On the north wall is a memorial to the great-uncle and great-aunt of Nurse Edith Cavell, shot by the Germans in Belgium in 1916, purportedly for spying, but renowned for her nursing care of soldiers from both sides of the conflict. Beneath her relative’s simple memorial plaque, is a framed picture of her with the story of her execution which was condemned world-wide. Interestingly, the name of Cavell will crop up again when we visit Hemley.

The Cavell memorial

The chancel boasts two standards – the Union Flag flying from the north wall above and just behind the unusual, possibly unique, banistered pulpit, and an RAF flag flying from the south wall.

The Union flag and the RAF standard fly over the chancel. Note the unusual bannistered pulpit. The pews came from St Clements in Ipswich in the 1950s.

As one exits the church it is impossible to miss the raised plinth bearing the grand Quilter family tomb and the stone urn behind it. They were benefactors here and at Sutton.

The Bawdsey Quay Information Panel on the Bawdsey Village website advises us that one of the noteworthy buildings in the village is the 19th century non-conformist chapel which is now a dwelling house, but of course, unlike the parish church, that has never been physically close to the waters of the Deben. Nevertheless, I did go in search of it and in so doing I passed an Edward VIII wall-mounted Post Office letter box, one of the last surviving it seems.

The Edward VIII Post Office letter box

If we reached Bawdsey by foot or on bicycles then we could now continue church spotting on the western shores of the Deben by taking the ferry from Bawdsey Quay to Felixstowe Ferry. However I have to admit that I have got thus far by car, for which the only available crossing is Wilford Bridge at Melton where we will visit what Simon Knott describes as the

‘wayward’ St Andrew’s. That will be the start of Part 3B.

Ferry, Car or even boat despite the chilly weather? Low water soon, judging by the horse, so could be a good run up-river with an incoming tide. But Brrrrr.

Dr Gareth Thomas MD., LL.M., FRCOG

Gareth Thomas retired as a local Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in 2010 and left the medicolegal world of Expertise in 2015. He and his wife Alison moved to Waldringfield from Rushmere Road, Ipswich in 2006, having previously lived in Nacton for nine years from 1979 – so they are getting to know the South Suffolk peninsula reasonably well! In 2007 Gareth became a founder member of the Waldringfield History Group and for ten years from 2010 he was Chairman of the Group. The end of his tenure of office coincided neatly with the publication of Waldringfield – a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben. The book was a combined effort on the part of all members of the small Group, but Gareth was one of the three members who took responsibility for the editing and management.

Gareth Thomas retired as a local Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in 2010 and left the medicolegal world of Expertise in 2015. He and his wife Alison moved to Waldringfield from Rushmere Road, Ipswich in 2006, having previously lived in Nacton for nine years from 1979 – so they are getting to know the South Suffolk peninsula reasonably well! In 2007 Gareth became a founder member of the Waldringfield History Group and for ten years from 2010 he was Chairman of the Group. The end of his tenure of office coincided neatly with the publication of Waldringfield – a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben. The book was a combined effort on the part of all members of the small Group, but Gareth was one of the three members who took responsibility for the editing and management.

Never known for sitting about, Gareth may be seen around Waldringfield walking his dogs, on the water on ‘Blazer’ or crabbing with some of his younger grandchildren. He is also too well known (in his opinion) for his involvement in the village pantomimes.

For the last twenty-three years he and Alison have had a family home in the valley of the Vezere in south-west France where Gareth has been able to maintain a managed meadow and plant well over one hundred trees.