by Gareth Thomas

Part 3: From MELTON and from SUTTON to the edge of THE NORTH SEA

*This might be just ten miles of estuary but it is two banks of a wide estuary and includes the ancient maritime town of Woodbridge. Consequently, for the sake of both compilers and readers, Part 3 is presented in two sections: 3A and 3B

Part 3B: From Melton to The North Sea

Back at Melton another St Andrew’s calls. Simon Knott describes it as ‘wayward’. A bit harsh, but I know what he is getting at. So far, we have seen churches struggling, sometimes against the odds, to maintain their medieval fabric on their original sites. In many cases their causes were advanced by Victorian wealth. In Melton, after much debate, that wealth was used to build a mock-up of medieval architecture on a completely new site, with stone not typical of this area, nearer to the developing township. It was completed in 1868. Somehow it lacks that aura of medieval mystery.

The Church of St Andrew, Melton

The interior of St Andrews, Melton. Note the rood screen

Inside, wayward or not, one cannot help but be impressed by the beautifully worked arch-braced hammerhead roof. There is a rood screen, but it does not date from the time of the original building. It was given by Sir William Churchman, in 1934 in memory of his wife.

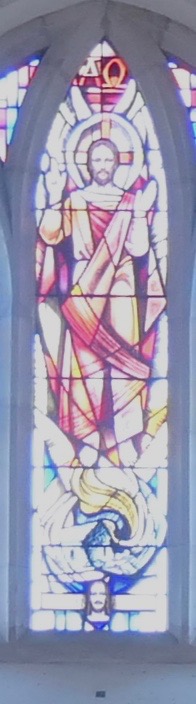

The stained glass is the work of Kempe & Co, a firm which was established about the time of the building of the church. It used a wheatsheaf as its maker’s mark and these appear in work carried out by them. A window in the south wall carries an image of Etheldreda also known as St Audry, who was the daughter of the 7th century King Anna of East Anglia. She founded a nunnery and hospice at Ely and was the Abbess there, but the significance of her depiction in this window in Melton is that, just up the road was St.Audry’s Hospital, formerly known as Suffolk Lunatic Asylum.

As I exited the porch with its three bell-ropes I bumped into a hospital work colleague of old whom I had not seen in years so that made the visit all the more worthwhile.

Such has been the development of Melton that one might be forgiven for thinking that the Church is far removed from the water but the distance is just short of 450 yards, so very much a Church of the Deben, built, no doubt, with proceeds from river-based trades.

Just around the corner in The Street and no more than 500 yards from the water there is a chapel, unmistakeable in its style but now home to a chiropody practice. It was built for the Primitive Methodists in 1860. Prior to that their place of worship was said to be at ‘Ranters Chapel Hired Room’ which had been ‘erected, consecrated or licenced’ as a place of worship before 1840 – whereabouts unknown (to me). According to Stephen Hatcher writing on methodistevangelicals.org.uk the Ranters were lay preachers, many of them women.

The story of the building of the Melton Chapel is really quite intriguing.

Melton Chapel – the chapel that moved – twice

In a document posted by Christopher Hill (cf Part 2 re Ufford) entitled ‘Melton – the chapel that moved’ Norma Virgoe, an authoress, described how a barrister living in a large house next door took legal action, claiming that his right to light had been infringed by the building. The trustees of the chapel lost the case at Bury Summer Assizes in 1861, whereupon a Melton millwright, Henry Collins, suggested that the chapel might be moved. An additional piece of land was purchased and the chapel was moved, on struts. The details of the amazing 15ft move were described in the Suffolk Chronicle and Mercury of the time. The building was described as ‘a neat and unpretending structure of red and white bricks.’ The move took three hours and there were no apparent cracks or scratches.

This story possibly explains why ‘Getty Images’ has an engraving entitled ‘removal of a chapel at Melton near Woodbridge’ taken from an old photograph of the event and showing lots of bowler hatted gents and bonneted ladies watching a few labourers. Copyright precludes inclusion here, but it is easily found ‘on the web.’ If the aforementioned barrister lived in the rather swanky house beside the chapel in the engraving, then one can see where he was coming from!

Unfortunately, the barrister restated his claim which necessitated a second move, making a total move of 20 feet 8 inches. According to Ms Virgoe the cost of the move was £31.12s 6d. but the legal expenses exceeded £750, three times the cost of the original building. (Ah well, nothing changes!) The Methodist Conference of 1862 paid £280 toward the bill but there is no record of where the rest of the money came from.

According to genuki the Methodist Chapel closed in 1965 but in 1988 Keith Guyler (cf part 2, page 39) described it as Independent, and myprimitivemethodists website believes it was still open in 2011 but not in 2015.

We progress, now, to Woodbridge where there are two parish churches, one Catholic church, a Salvation Army Church, a Methodist Church and a Baptist Church all within easy reach of the quays and the river. A seventh church, the Warwick Avenue Evangelical Church, is in the Melton Farm Estate area of Woodbridge. The church was started by one Doris Adams in a butcher’s shop in 1942, progressing to an old windowless army hut which had to be moved from the centre of Woodbridge, still in wartime. Their website shows how it was soon after. avenueevangelicalchurch.org.uk.

Warwick Avenue Evangelical Church in the late 1940s. Taken from their website.

Warwick Avenue Evangelical Church built in 2006. Now well supplied with Broadband, we presume!

Woodbridge and the River Deben was not immune to attack in the Second World War and many of the women and children of this then new congregation would have had husbands and fathers who were either fighting overseas or involved militarily at home, often in development or in defence, both of which were happening ‘big time’ on this river. Thus it qualifies as a Church of the Deben.

The other churches of the town may be visited by one almost simple circuit starting at the turning into Quay Street opposite the Riverside Cinema. Less than a hundred yards up the street on the right is Woodbridge Quay Church which started life as a new build for the Woodbridge Congregationalists in 1806. In 1972, following the merger of the majority of Congregational churches with the Presbyterians, it became Quay United Reformed Church which later merged, on the same site, with Beaumont Baptist Church and is now a member of the Baptist Union of Great Britain, and the Evangelical Alliance.

Woodbridge Quay Church – looking down towards the river. One can see

why it was necessary to move the entrance off the street.

A good pair of hands

The church is probably best known for the large sculpture of Praying hands in the church grounds. It is sometimes referred to as ‘The Church with the Hands’. However, it is not the first ecclesiastical building to occupy this site. From thequay.org.uk/quay-congregational-church-history we find that the ‘Quay Congregational Church was formed in 1651 by the Rev. Frederic Woodhall, together with 55 “brethren and sisters”. He first exercised his ministry at the Parish Church and probably continued until the Act of Uniformity (1662) was passed. Then he would have been ejected from his living and imprisoned for his ‘independent views.’ In 1672, courtesy of Charles II proclaiming an ‘Indulgence’, albeit short-lived, he became licensed as a Congregational Teacher at the house of one Jonathan Basse, which was licensed for worship, and afterwards the Church assembled in a room adjoining the Ship Inn. Both Revd. Woodhall and Jonathan Basse died in December 1681 having lived through decades of religious turmoil, and the Civil War. Religious persecution resumed on a large scale in 1681.

A chapel, capable of seating 500 people, was built on the site of the Quay Church in 1688 but life for non-conformists was difficult and the congregation decreased through the next century. In 1787 some members left to worship at the house of Jonathan Beaumont, who later built a chapel in Cuttings Lane.

The present church was erected on the site of the old one, in 1805. Several pastors in the first half of the 19th century referred to “serious difficulties” and “the work in Woodbridge [being] connected with difficulties of no ordinary description.” But whether these difficulties were within the non-conformist congregations or with authorities, or the established church is not made clear. All are possible; the town in which I was brought up in Buckinghamshire had four Baptist churches and one Congregational church all in the main street and two of the Baptists were next door to each other! (The Trimleys also spring to mind but that’s another story)

In 1877 the front door of Quay Church was taken to the side to allow widening of the road. (It is still pretty narrow!) Then in 1897 there was a major refurbishment including the introduction of gas lighting. The Church is said to have prospered at this time and a new schoolroom was built. During both world wars the halls were used for canteen and recreation rooms for troops stationed in the town. Where the Hands are now was evidently used in WW1 for the cultivation of vegetables. That was a time when Enid Blyton, the children’s author taught in the Sunday School whilst living at Seckford Hall.

Electric light was installed in 1924. In 2001, after several major works on the fabric of the current building, the membership celebrated its 350th Anniversary. In 2006 the church re-united with Beaumont Baptist Church. The Baptist Church purchased the building from the United Reformed Church and the combined church became known as Woodbridge Quay Church.

Quay Lane becomes Church Street at the junction with the Thoroughfare. On the left towards the top of Church St. is the entrance to the Abbey School, the older part of which was the home of Thomas Seckford. That, in turn, was built on the site of Woodbridge Priory which was founded in 1193 and, sited in the centre of the township, provided education, religion and nurture for the community for the best part of 350 years before being ‘dissolved’ on the orders of King Henry VIII in 1537. As we will see shortly, there was no separate church for this Priory; the Church of St Mary the Virgin was next door.

The site of the Woodbridge Priory – eventually the home of Thomas Seckford

St Mary’s, Woodbridge is the centrepiece of the town, described by Suffolk County Council as ‘a glorious 15th Century flint-faced church, housing the tomb of Thomas Seckford, the 16th Century father of the town. He was a barrister and a shipper. In his time, 1515 -1587 he was Master of the Court of Requests of Queen Elizabeth I. He ran a thriving ship building industry in Woodbridge. It is said that he was not entirely averse to smuggling.

According to M A Weaver and J N Stevens, authors of the church guide, there was a church very close to the current site of St Mary’s in 1086 AD, thought to have been built toward the end of the tenth century. The Priory was built about one hundred years later, on the site next to and just south of that church which served as the Priory church. The Augustinian Prior was the Rector of the church.

The clergy of the Priory obtained licence for a market, and prosperity reigned. About 1400 a decision was made to start building a new church on land immediately north of the old one. The tower and the porch are thought to have been completed about 1450. The tower, which took 9 years to build, is 108 feet tall. One of its three main benefactors, John Kemp, was a merchant ship owner. It is thought that for almost a century there were two churches; indeed, the structure of the east end of the south wall of the current building, and the old door within it, suggest they may have been partly attached.

Then in 1537 the Priory was sacked on the orders of the King. The church was stripped of all its treasures, the old church was demolished and the Priory and its land were given to Sir Anthony Wingfield by the King but were later purchased by Thomas Seckford. For comparison, to place these events in perspective, the Shire Hall was built in 1575.

The 15th century tower of the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Woodbridge.

If people are going to park their cars right outside the west door then they could at least keep the colour down!!

The Shire Hall, Woodbridge

Standing near the Shire Hall one would never imagine the tower at St Mary’s to be visible from any great distance, despite its height. There seem to be too many trees and buildings around it. But walking northwards on the river wall out of Waldringfield one can see just how useful a navigation aid it must have been in earlier centuries.

The Church of St Mary, Woodbridge as seen from the river wall at Waldringfield.

Such was the demand for seating at St Mary’s that wooden galleries were erected between 1627 -1638 (and again in 1777-1813). In 1644 ‘Smasher’ Dowsing visited and damaged the font and the rood screen on behalf of the Puritan government. Old oak benches with their poppy-head pew ends were destroyed and replaced with box pews. A series of papers entitled ‘Pews, Benches and Chairs’ presented over 514 pages by the Ecclesiological Society in 2011 does not appear to refer to any specific objection of the iconoclastic Puritans to pews or pew ends but I fancy I read somewhere that they took exception to the ‘idolatry’ carvings on pew ends either in panel form or as ‘poppy heads’.

The guide-book tells us that in 1863/1864 the decayed North porch was restored and ‘the unsightly filthy urinal on the west side, between the porch and the steeple was taken away.’ The three figures in the niches above the door were placed there at that time, previous figures having been removed during the Reformation, one presumes. In the porch there is a ‘dole cupboard’ provided by John Sayer, yeoman of Woodbridge in 1635.

Gradually, over the subsequent years, the galleries, box pews and three tier pulpit have been removed but a piscina (15th century small stone basin) and sediliae (15th century recessed seats) have been discovered in the south wall of the Sanctuary opposite the tomb of Sir Thomas Seckford.

The font shows clear signs of the Dowsing activity. Like many others we have seen, it is octagonal with eight carved panels. These, evidently, are peculiar to Norfolk and Suffolk. St Mary’s is one of only three which have the Crucifixion as the eighth panel. The intricate font cover is modern.

The beautiful 15th century North porch

It is best not to wonder about the urinal

The three figurines replaced in the late 19th century

John Sayers dole cupboard promising distribution of bread amongst the poor of the parish every Sunday for ever – quite a promise

There are many memorial plaques, and it is impossible in an article like this to do them justice. However, my attention was drawn to that of Rear Admiral William Carthew 1827, so I looked him up and found a good read on morethannelson.com. Brought up in Woodbridge Abbey which his father owned he had eighteen siblings or step-siblings. He went to Ipswich School, joined the navy, and had an extremely adventurous life.

Another man of the Royal Navy is buried in the churchyard and commemorated. Lieutenant John Clarkson (1764 – 1828) was an abolitionist who organised a fleet to take 1200 slaves from America to set up an experimental colony in Sierra Leone, namely Freetown. He and his brother were founders of the ‘Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace’. How the world needs them now! He ended his days as a banker in Woodbridge.

The church guide draws attention to the rare Dutch candelabrum in the nave. Given to the church in 1676, it survived the installation of gas in 1841 when many such articles were jetttisoned. The guide also points out the fact that, inexplicably, the east window is off-centre – not that you’d notice!

The nave and chancel of St Mary the Virgin. Note the off-centre East window and the candelabrum. This Church is light and airy thanks, in part to the two lines of large, clear clerestory windows.

We continue our clerical circuit of Woodbridge by ascending the steps from the churchyard to the Town Square and Shire Hall, then over into New Street in order to make our way back toward the river and down to St John’s Church. But hang on; immediately to our left there is a Chapel Lane and we know from our experience in Wickham Market in part 2 that Chapel Lane usually means a chapel. Sure enough, on the left there is a very fine-looking building, now a private dwelling place, but complete with laterally placed doors, lateral pinnacles and a cross at the apex. This, I imagine, was the Beaumont Baptist Chapel referred to earlier, but I might stand corrected.

The steps up to the Town Square

Down New Street, past the Bell and Steelyard on the right and the Old Mariner on the left, toward the bottom we have to turn off the circuit to ascend St John’s Hill toward St John’s Church which was built as a ‘daughter’ to the ancient St Mary’s in 1842. In the early part of the 19th century Woodbridge was growing rapidly, thanks partly to military barracks at the edge of town and thanks to the fact that river-based activities were still in full swing. The old parish church was full to overflowing. The 1830s had seen a religious revival in the town at a time when St Mary’s wooden galleries had been dismantled.

St John’s website tells us that forty-two potential designs were submitted. The plan submitted by the town’s leading builder was accepted and he also got the contract to build the church! The account says that the laying of the foundation stone was part of a grand Masonic affair in the town, but they take care to deny any such connections today.

The building, which took 4 years to build and cost £3000, would seat 800 people because there was a gallery extending from the rear along both the south and the north walls.

The ecclesiastical parish of St John was formed in 1854. Another religious revival in Woodbridge in 1876 is said to have been largely due to the untiring efforts of the then vicar. Despite that, the side galleries were removed in 1896, the year that a bell was hung.

In 1913 a tower clock was installed ‘for the townspeople’.

The Church of St John, Woodbridge

For me the very perpendicular appearance of the west window gives the building a rather grumpy look which does not reflect the comforting interior

The tower clock at the Church of St John

The tower and spire reached a combined height of 138ft but unfortunately the pinnacles started to crumble and, in 1945, they had to be reduced to half their height. The spire was deemed unsafe and therefore removed in 1975. Since the 1980s modernisation has been the theme – for instance, lighter interior decoration, removal of the pulpit and choir stalls to make way for a raised carpeted dais and new clerical furniture, provision of a new vicar’s vestry, a servery, toilet facilities, and stackable upholstered chairs, a digital organ and PA system and, in 2002, a new spire.

The new spire at the Church of St John

A comforting colour scheme in the nave

The back part of the gallery remains and has been used to help

form the new facilities at the entrance to the church

As I passed through the entrance foyer a lady emerged from the servery (kitchen) clutching half a dozen chocolate finger biscuits. She explained that she was clearing up after the mid-week communion. I had to smile – my sacrilegious sense of humour insisted. The lady was very helpful and, together we listed the seven churches I needed to visit in Woodbridge. It was when she said ‘and’ after the seventh that I said to myself, ‘Please G, no more’, she realised that she had run out and I breathed a great sigh of relief. We are never going to get to the North Sea on this side of the river!

If you were to fly a drone 50 yards in a south, south easterly direction from the roof of St John’s you would be able to land on the roof of the Catholic Church of St Thomas of Canterbury. By foot it is about 150 yards around the corner, in St John’s Street. It is part of a joint parish with the Roman Catholic Church in Framlingham and is part of the diocese of East Anglia. I first became aware of this church when my daughter lived in a terraced house just next door but a few. I failed to work out why there was a church in a line of terraced houses and why it seemed to be two buildings. Perhaps one was the presbytery, I thought – wrongly.

Simon Knott explains pretty well everything about this church, and indeed the local history of Catholicism, on his website suffolkchurches.co.uk. For me he even explains why I once had a patient who lived in Rushmere who maintained that her bungalow had once been a convent, although from the outside it looked – just like a bungalow. It appears it was temporary accommodation for a group of Carmelite nuns. So that explains that!

The Catholic Church of St Thomas of Canterbury, Woodbridge

The nearest part is the old Temperance Hall, and the far part is the entrance

The original Catholic church in Woodbridge was, of course, St Mary’s but that all changed with the Reformation and subsequent Puritanism. The Act of Uniformity (1559) rendered public worship in the Catholic faith difficult, if not illegal, in England and that situation prevailed until the end of the 18th century.

The first post-reformation Catholic Mass in Woodbridge took place in a private house in Church Street in 1865. Just over a decade later Mass was taking place in a warehouse but in 1871 a purpose-built church was constructed on a plot of land in Crown Place. This was just round the corner from the Woodbridge Quay Church and, similarly, very close to the river. It was used for the next 58 years before moving to the current church.

The church is only open when Mass is being celebrated but Suffolk Churches carries some beautiful photographs of the interior which I could not begin to emulate. The building(s) started life as a Temperance Hall in 1850 and later became home to the YMCA. They were purchased for conversion into a church in 1929 and there has been considerable refurbishment within the last fifteen years.

About 150 yards further along St John’s Street we find Woodbridge Methodist Church, standing proudly on the corner showing off its decorative brick work and its carved stone friezes – what architects describe as ‘semi-Italianate’. There are two front doors, one to each side of the frontage and there is a tall, triple window in the centre.

Audrey Robinson compiled a detailed history in 2010. She tells us that ‘Methodism arrived in Woodbridge in 1812’ (Wesleyan Methodism to be precise – as opposed to Primitive – but don’t ask, because I don’t know the answer!) when the Lincolnshire Regiment were stationed at Woodbridge Barracks. One of the drummers was also a Methodist Local Preacher; services were held, and some townspeople attended. Initially meetings were held in rented rooms and, for a time, in a sand pit possibly near Deben Mill. Eventually, about 1829, land was purchased in Brook Street and a chapel was built there – yes, another! It is now a private dwelling place with four swift boxes under its eaves and no eccliastical windows. Methodism flourished there but it was too small, and Brook Street was, and still is, rather narrow for access.

The site in St John’s Street was donated by Mr Charles Andrews of Ipswich, money was found and the new Wesleyan Chapel was built in time to be opened in May 1872. In 1932 the two branches of Methodism united and both became simply Methodist. Before 1950 the church in St John’s Street was ‘head of a section consisting’ of Bawdsey, Butley, Hollesley, Ufford and Melton two of which have already featured as ‘Churches of the Deben’.

Major renovation was required in the early 1960s mainly because of dry rot. Then, in the 1980s, a decision was taken to expand the premises to cope with all the activities and social interaction which was taking place not only within the local community but with peripherals also. The new build was called the Octagon but major changes were also made inside the church Sanctuary. Much of the work was carried out by a team of more than a hundred volunteers, described by a local paper as ‘teenagers to the silver-haired brigade’, using any talents anybody could offer.

Woodbridge Methodist Church and the inevitable parking.

I notice the Methodists have started to drop their ‘H’s but reading about this congregation and its ability to call on skilful volunteers convinces me that it will not be for long

The Octagon – beside the Church – built by volunteers

From the semi-Italianate Woodbridge Methodist Church we can walk fifty yards to the traffic lights and turn right into the Thoroughfare to make our way to the last of Woodbridge’s Churches of the Deben – last but not least. A walk down the Thoroughfare is always relaxing – there is very little traffic, very little rush and yet plenty of activity. It is good to see that individual shops and cafes can still survive. People drive from Essex on a Saturday morning to take in this sort of ambience and, of course, it is only a stone’s throw away from a walk by the river and the ancient Tide Mill.

As we reach the geographically lowest part of the Thoroughfare we can turn right, back into New Street. Here it is pedestrianised; there are two or three shops and then the headquarters of the Woodbridge Salvation Army in St John’s Church Hall. From the front it appears purely functional, perhaps ‘sixties modern’, and unobtrusive but from the side it is apparent that this building is ‘of an age.’ There are six pairs of ties in the side wall which must suggest that it dates from the early nineteenth century – I am sure somebody in the Woodbridge Society would know the answer.

The Salvation Army was founded in the East End of London in 1865 by William Booth and his wife Catherine. He had been a Methodist minister. The theological doctrine of the Salvation Army is based on Methodism but the organisation is always careful to point out that it is a totally independent denomination of the Christian church. Its policy is to try to ensure that ‘everyone experiences life in all its fullness’. In the UK it is one of the largest non-government providers of social services and in the USA it is the largest; the organisation works in 134 countries, world-wide. Here, in the Woodbridge headquarters, they run a food bank and they have a charity shop in Gobbit’s Yard just off the Thoroughfare.

The front and side of the Salvation Army Church and Community Centre in Woodbridge.

Well, in Woodbridge alone we have discovered an old Priory and seven Churches of the Deben, not to mention at least three old chapels/churches which, in their time, would have been Churches of the Deben. Now it is time to move on but not before a look at the longship to take us back to ancient times.

Down-river, on the western side we come to Martlesham Creek which is where the River Finn drains into the Deben, over mud-flats. The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Martlesham stands above the south side of the creek, next to Martlesham Hall and the Rectory. Some buildings associated with the Hall have been converted into workshops for artisans but otherwise this is a pocket of buildings which has become isolated physically from the rest of Old Martlesham with its old coaching inn, the Red Lion, and the road bridge over the Finn where, prior to 1929, there was simply a ford. It is possible that this separation was the result of the Black Death pandemic in 1348 but the increasing use of road transport and the presence of a ford and a coaching inn at the head of the creek may have caused the focus of the village to move.

There is evidence of Roman occupation in this area and the Domesday survey recorded the presence of a church. The current church was built of flint, rubble and brick early in the 15th century. It boasts three guides on the Suffolk Historic Churches website – one for children, provided by The Arts Society Church Trails, one older guide by H.R Lingwood and one more recent but undated and unattributed. The more recent guide advises us that there was a ‘brickyard nearby at one time which sent bricks by water as far as London’. It has been said by others that bricks from this area were taken to the USA for the building of the White House. It is likely that the 15th century font and heavy stones used in the construction of this church were brought by water and that, at one time, the creek was much deeper than it is now.

The path to the Church at Martlesham

You have to imagine the magnificent birdsong

The footpath to the church is enclosed by overarching trees and the birdsong is truly magnificent. Eventually one reaches a clearing with the west door and the tower basking in the sunlight. It is not possible to see either the Deben or the creek from the churchyard but somehow you know that they are there, in the valley to the east and in the creek to the north. It is an extremely peaceful, and still-used graveyard.

Outside, an intriguing feature is the Victorian add-on to the chancel which housed the Rector’s family pew. The tower is very well proportioned and easy on the eye.

The first treasure one sees on entering this peaceful church by its original, oak, south door is a wall painting on the north wall of the nave. It is a depiction of St Christopher carrying Christ on his shoulder. It was painted about 1400 and, having been whitewashed out in the Reformation, it was re-discovered in 1902 and conserved following cleaning in 1989.

The organ in this church is of personal interest to me because it is said to have come, in 1976, from a Congregational Church in Wrexham, my place of birth. I was christened in Salisbury Park Congregational Church where my father was the minister. This organ might have played at my christening! Enquiries are ongoing! It is positioned in the north-west corner of the nave and it appears to be accessed from the tower room through a very narrow space – all organists here must be of the slim variety.

The Church of St Mary the Virgin at Martlesham from the east

The tower is very pleasing to the eye but the Victorian extension to the chancel is odd, to say the least (wait until you get inside!)

Wall Painting: St Christopher carrying Christ on his shoulders

The first treasure one sees on entering the church

Not far from the organ, in a blocked north doorway there is an ancient deal trunk which was noted to be in the chancel in 1829 but found doing service as a feed bin in the Rectory stable in 1859. The lid is made of a hollowed poplar trunk.

The trunk rescued from the rectory stable in 1859

The chancel was rebuilt in 1833 using earlier roof timbers. The east window required a rebuild in 1905 because of subsidence. On the south side, in the small Victorian annex we saw from the outside, there is a family pew made from panels which came from the rood screen. It was used by the Doughty family which first became associated with the church in 1698 when George Doughty became the Rector. The guide tells us that his grandson married into the Goodwin family of Martlesham Hall and that, thereafter, members of the Doughty family were either Rectors or patrons from 1798 until the death of Mrs Blanche Doughty in 1970. She was the widow of the Revd F.E. Doughty who was the Rector from 1915 to 1944. The Doughty family feature frequently in the Perennial diary of Thomas Henry Waller (of Waldringfield) of which I have written before in this Journal.

It is difficult to imagine how the occupants of the Doughty pew would be able to hear any sermon delivered from the 1614 pulpit positioned in the north-east corner of the nave but perhaps they had heard it all before, at home!

The chancel roof is simple hammerbeam with arched braces but there are twelve shields, one on each beam, each representing an apostle. These were added in the early 20th century. An unsuccessful attempt to photograph all twelve shields at once resulted in my lying on my back in the centre of the chancel aisle, praying that nobody would enter the church at that time lest they thought they had walked in on an episode of Midsomer Murders.

8 out of 12 shields : the best I could do lying flat on my back on the chancel floor!

The older church-guide draws attention to some telling findings in the churchyard such as the headstone, dated 1823, of a farmer who was buried with his 27th and 28th children. The guide goes on to state that the farmer’s only wife, ie mother to all 28 children, lived until she was 81 years old. Another headstone commemorates one couple’s ten children, all of whom died in infancy. It seems that in 1728 smallpox was rife and, that year, there were more than three times the average number of burials. However, we can leave on a brighter note just listening to the birds in this peaceful place.

Our next ‘port of call’ is Waldringfield where there are two churches, All Saints’ (the parish church) and the Baptist Chapel.

All Saints’ is situated close to what was, before the river walls were built, a creek. It is likely that the font and heavy building stones were lifted up the small cliff from boats in the creek.

The Church of All Saints, Waldringfield

The tower is built of small Tudor (1485-1603) bricks laid in patterns and the window is of classic shape for that time. Round the corner, in the south wall, to the left of the porch there is a classical, single lancet window, dating from about 1220. It is better viewed from the inside.

Single lancet window

circa 1220

This suggests that the main body of the existing church dates back about 800 years. Although there is no mention of a church in the Domesday Survey of 1086, there are various reasons for believing that the church site was used for worship, possibly even pre-Christian worship, for at least two or three centuries before the existing stone church was built. The catholic dedication to the festival of ‘All Saints’ rather than to a specific saint tends to be found in older established Christian churches. We are aware, also, that Christianity was introduced just a few miles across the water, between 605 and 878 AD.; 605 AD when, according to the Venerable Bede and recent archaeological finds at Rendlesham, the Anglo-Saxon King Raedwald started to break away from paganism; and 878 AD when the local Viking ruler Guthrum, converted to Christianity.

Unfortunately, neither of these factors can be classed as evidence per se of an earlier place of worship; it is merely speculation. Even the discovery in 1985 of iron age artefacts in the graveyard fails to provide the evidence we need. These are fragments from fired clay moulds, used to cast Iron-Age (800BC to 43AD) horse harness; they are thought to date from about 50 BC to 43 AD and are now kept in the British Museum. The horse harness was inlaid on both sides with red glass thought to have been brought from the Eastern Mediterranean.

On entering the church there is an interesting octagonal font, with supporting angels, interesting because of its almost perfect condition; it seems to have been spared the attention of Smasher Dowsing, despite its prominent angel wings. However, we presume that the rood loft was removed because its timbers are said to be found in the roof of the porch.

Whilst we can be fairly certain that the nave of Waldringfield Church was started early in the 13th century the other windows in the nave and the chancel, are decorated Gothic, more indicative of building in the first half of the 14th century, presumably before the start of the bubonic plague or Black Death in 1348.

Decorated Gothic windows of the nave and the chancel

Note the original depth of the window between the buttresses. The original window was designed probably to allow the passage of alms from inside the church to the outside or to allow outcasts to see in at the time of Mass. Some-times there was a hatch to allow the ringing of a hand-bell to signify that Mass was about to begin.

Like many other churches, All Saints at Waldringfield fell into a state of disrepair in the late 1700s/early 1800s. In 1848, during the incumbency of Rev Alfred SUART (1848-62) the church was described as having ‘no more pretentiousness to architectural elegance than a well-ordered barn’. It took the Victorian wealth of the Industrial Revolution to fund restoration. Now, for instance there are beautiful stained-glass windows.

The Coprolite window

The East window is known as the Coprolite window because it was paid for, like other improvements, with money made from the coprolite industry. The West window is in memoriam to the Reverend Thomas Henry Waller and to his wife Jane nee Pretyman (of Ramsholt) – also to their grandson, who was killed in action in the first world war, but not at Arras, as recorded in the glazing.

Waldringfield is well known locally for the fact that four generations of one family provided four Rectors sequentially. Thomas Henry Waller became the Rector in 1862. He was succeeded by his son, Arthur Pretyman Waller who was succeeded by his son, Trevor who was succeeded by his son, John Pretyman Waller. This bears a great similarity with the Doughty family in Martlesham. Rev.Trevor, and later Rev. John, had a boat on the moorings at Waldringfield called ‘Jesus’ and the tender to the boat was called ‘little Jesus’. Jesus is still to be seen but little Jesus disappeared in a storm several years ago. The ‘disappearance of little Jesus’ causes considerable consternation especially if heard out of context!

Before we leave All Saints’, Waldringfield we should mention two subjects specific to this church.

First, the “Ring of Churches’ about which I wrote in Part 1 of this series. Essentially the Church of All Saints in Waldringfield appears to lie at the centre of a circle with a radius of two old Suffolk miles (an old Suffolk mile being 1830 yards) on the circumference of which lie Brightwell’s ‘Church of All Saints and St James’, Martlesham’s ‘Church of St Mary the Virgin’ and Sutton’s Church of All Saints’, with Ramsholt’s ‘Church of St Michael’ lying just 60 yards inside the circle.

The Newbourne ‘Church of St Mary the Virgin’ and Hemley’s ‘All Saints’ Church’ lie about 50 yards either side of the line marking a distance of 1830 yards from Waldringfield All Saints’. These churches all appear to have been built at a similar height above sea level, ie on the same contour line. The distance of 1830 yards (or double that at 3660 yards) might not, at first, seem particularly significant but, in papers prepared for the Debenham History Society, David Aldred described 1830 yards as ‘a distance frequently noted regarding [Saxon] field measurements in Suffolk’, sometimes referred to as the ‘Suffolk mile’.

These findings are intriguing. One has to bear in mind that parish churches may well have been built on pre-Christian (pagan) religious sites. Conversion to Christianity was probably sufficiently gradual to allow continued use of the pagan sites, first, perhaps, by building a wooden place of worship and then, as the new religion took hold, replacing the wood with stone. There might be a pagan explanation for this ‘Ring’ but co-incidence is equally possible. In my study of the Churches of the Deben I have found no other geographical relationships of this kind.

The second subject is the Yachtsmen’s Service in which the moorings and the beach at Waldringfield become a place of worship just once a year. In 1936 Canon Arthur Waller started the tradition of an annual yachtsman’s service in Waldringfield Church. In 1949 Revd. Trevor moved the service to the shoreline outside the Waldringfield Sailing Club and since 1952 the preacher has been brought from Ramsholt on board a yacht escorted in fleet formation by many other yachts, all dressed overall. The music is provided by the Woodbridge Excelsior Band on-shore and the service is conducted from the leading yacht.

There is, of course, another place of worship in Waldringfield, at the edge of the village, on Waldringfield Heath. Its inclusion here is warranted, as with the Evangelical Church in Woodbridge, not so much by the geographical relationship between the building and the river, more by the relationship of its congregation with the river. At the turn of the

twentieth century, for instance, the families of a significant number of workers from the Cement Works in Waldringfield were attending the Baptist Church.

The Baptist Chapel at Waldringfield Heath

The Baptist chapel was built in 1823 at a cost of £110 on land donated by Mr Lacey of Stoke Church in Ipswich. Fifty pounds came from the legacy of a member of Maidstone Baptist Chapel in Walton. It was built to be functional rather than decorative and designed to allow extension, which proved necessary quite quickly.

Rather than architectural heritage, the Chapel provides us with social history through the 19th and 20th centuries mainly through its well-preserved minute books, also through its graveyard and, to a lesser extent, through photographs

Baptists do not practice infant baptism – perhaps wisely in Waldringfield, as baptisms in those early days took place in the River Deben at the ‘Cliff’. Such services drew large, noisy crowds, some of them straight out of the Maybush so, in 1843, a baptism pool was built within the chapel at a cost of £4.10 shillings.

Two years later, Mr Lacey donated another piece of land on which to build a house for the pastor. It was completed in 1846 at the same time as a new porch and vestry for the chapel.

The minutes show that the membership of about 50 (1848) offered to supplement Pastor Dawson’s income by a penny a week so that he could start a school.

The Porch and side vestry showing the graveyard to the right

The minutes of 1915 refer to the need to darken the windows as there were Zeppelin air raids finding their way over this area toward more distant targets.

The Waldringfield Baptist Chapel did not fare well in the second world War. In September 1940 two bombs dropped in a field nearby. Windows and hundreds of roof tiles were broken, doors were blown in, the vestry unroofed and the Manse and stable were damaged.

The cost of repairs could not be fully met so, for the rest of the war, meetings were held in the Village Hall.

The back of Waldringfield Baptist Chapel

The back of the chapel today shows renovations and extensions which have taken place in the 79 years since the end of that war.

Members of the Waldringfield History Group have transcribed and recorded the gravestone inscriptions in the burial ground, the earliest burials going back to the beginnings of the Chapel in 1823. These are available online, at Gravestonephotos.com.

We now need to consider the remainder of the western shore of the river, as it is now and as it was before the river walls were built.

Almost equidistant from All Saints, Waldringfield are the churches at Hemley and Newbourne, each just one Suffolk mile away. Hemley remains a shoreline village, but Newbourne has ‘retreated’ inland.

Hemley Church

Hemley Church, also called All Saints, was listed in the Domesday survey of 1086. It is likely that a church building had been on this site for years, or even decades, before that but the windows in the nave and chancel show the Gothic characteristics of the 14th century

The tower, like that of Waldringfield, is Tudor brick, late 15th/early 16th century. The oldest treasure within the church is the font which is made of Purbeck marble and has a very definite Norman appearance of the 12th or 13th century.

The Purbeck marble font at Hemley

Evidently, by the early 19th century the church had become very dilapidated. The chancel had been shortened and a new east wall built.

The East wall at Hemley

Restored sometime prior to 1843

Note the inclusion of a gravestone on the left

The script associated with a drawing of the church by Henry Davy in 1843 refers to the William Cavell gravestone being part of the East wall. I find it somewhat bizarre that a gravestone has been used as part of a wall restoration, especially when that particular gravestone carried the names of ancestors of someone whose name would become well-known in a future century.

In 1889 the nave, chancel and porch were entirely rebuilt, but old materials were re-used, particularly, I should imagine, the 14th century stonework arch of the now blocked north doorway, all the windows and the arch of the south doorway under the porch. The east wall, I imagine, was already as it is now with the headstone of William Cavell’s grave included in the structure.

The project was financed to the tune of £2000 by Mr Richard Porter of Rushmere. One of the architects involved was Frank Barnes who also designed the new Melton Parish Church of St Andrew, some non-conformist churches in Ipswich and the railway stations at Stowmarket and Needham Market.

The carpentry of the 1889 rebuild is impressive from the moulded oak barge-boards of the porch to the pitch pine waggon roof of the chancel and the king-post roof of the nave.

At Hemley; the impressive Victorian carpentry seen in the barge-boards of the porch, the waggon roof of the chancel and the king-post roof of the nave.

The church is also proud of its 17th century communion table and its impressive reredos (that is the panelling behind the altar), complete with Cherubs. Not realising until recently that the church had been rebuilt in Victorian times I had wondered how the cherubs might have escaped the attention of Smasher Dowsing but from the church guide we learn that the reredos was rescued from a shell shattered church in Belgium in 1918 by Major Moncrieff of Hemley and was presented to the church by his nephew in 1981.

The cherubs came even later – we are assured they are made of wood but we have been told that there are some moulds for cherubs knocking around somewhere in Hemley and bearing in mind that 11 of the 14 hammer-head beam angels in Bromeswell are made of fibreglass, one has to worry.

A walk from Hemley to Newbourne, taken in wet weather, provides convincing evidence of there having been a waterway through the valley at some point and folklore has it that barges would tie up close to the Fox (or perhaps close to a pre-existing building as the existing pub is ‘only 400 years old’ and the river walls might be slightly older!)

The flint tower of St Mary’s,Newbourne stands proud with its pinnacles, keeping watch over the small community below, including The Fox, one of our favourite places for a Sunday roast.

Newbourne – the church tower keeps a watchful eye

The tower was well buttressed when it was built and later buttresses have been added to the west wall of the nave, suggesting maybe that the soil hereabouts is rather sandy. The tower, being a south wall tower, provides access to the south door into the nave. The magnificence of its base is lost somewhat by the addition to the south wall of a red-brick south aisle.

The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Newbourne; from the south

Inside there is a restored octagonal font and a very neat example of rood stairs arising from the top of the pulpit steps. The east window dates from 1987 when the old one was blown out by the famous gale of that year, the Great Storm. There is a commemorative plaque which records the event. Evidently a piece of glass from the old window carried an impression of Christ’s head. It was rescued ‘miraculously’ from a pile of rubble and included at the base of the new window.

To the left of the path as one comes out of the church there are four tombstones commemorating members of the Page family, one of whom was referred to as ‘The Newbourne Giant’. The headstones are in a neat line but there is one footstone out of line which makes it quite easy to tell which one was the Giant.

The Page family graves. Note the third footstone from the foreground

The rood steps follow on from the pulpit steps and the pulpit platform

The Great Storm of October 1987 remembered

The head of Christ recovered

One and a half miles almost due west of Newbourne is Brightwell and its Church of St John. The River Mill passes through the village on its way to Kirton creek and its confluence with

the River Deben. The presence of parallel water courses starting to the east of Brightwell and extending to the confluence suggest that the creek was much wider and probably deeper before the building of the river walls. The creek may well have extended as far into the peninsular as Brightwell, dividing at one point to extend as far as Newbourne, much as W.G.Arnott’s aforementioned map suggests. That map appears, also, to put Bucklesham close to the water’s edge but the stream passing through Bucklesham today is very much a tributary of Mill River and it is very difficult to imagine it as a working waterway.

The modern topography of Brightwell, however, is more in favour of a working waterway. The Church of St John the Baptist in Brightwell is set near the top of a hill. I pass there several times a week in both directions and as I descend into the verdant valley below the church, I find it easy to imagine its river, the River Mill, being a much greater, wider stretch of water than it is today. The village sign stresses the significance of the river, depicted it passing sinuously from the lower edge to the top. It strikes me, rather unexpectedly I admit, that Brightwell may well be a Church of the Deben.

The verdant valley of the River Mill as it passes through Brightwell.

The church guide was ‘revised and extended’ by Roy Tricker so it is full of interesting information including the fact that the Church and its environs were painted in oils by John Constable in 1815. The painting ‘Brightwell Church and Village’ is in the Tate Gallery.

The Church is situated immediately adjacent to the estate which once surrounded Brightwell Hall, the home of Sir Thomas Essington. Partly because of that proximity, partly because the church is small and partly because there are, within, memorials to two of three Essington youngsters who died young, the Church has often been considered as the Brightwell Hall Chapel but it is, in fact, the parish church. The Essington parents are at rest beneath a ledger stone in the nave and the next family to own the Hall, the Barnadistons, lie in a vault in the sanctuary.

The Church of St. John, Brightwell – note particularly the pinnacles which were placed

there despite the views of the Puritan government of the time.

The church was mentioned in the Domesday book but, judging by the doorway arches and the windows, the church we see today was built in the late 13th, early 14th century. It fell into a ruinous state in the late 16th and early 17th centuries but was restored by Thomas Essington in the 1650s, not long after ‘Smasher’ Dowsing had visited in 1644 and ordered the usual destruction of imagery. At the time of the church restoration, which included the tower and tower arch, pinnacles at the corners of the building, the font cover, the pulpit and a chalice, Cromwell was still Lord Protector; Roy Tricker indicates that it was very rare for a church to be restored in this way at that time.

Further restorations took place in 1876, 1897 and the 1950s.

Kirton Creek, where the River Mill joins the Deben, is the best part of a mile from the Church of St Mary and St Martin in Kirton and, quite possibly, always has been. Kirton is very much in the centre of the narrow, south Suffolk peninsular. The village sign depicts subjects to do with the smithy, the church and with agriculture; there is no obvious reference to anything nautical so it might seem reasonable to do no more than mention the church in this account.

Lanes to the left of the main road through Kirton all lead either toward the marshes or back to Kirton; the main road, itself, leads directly into the northern boundary of Falkenham.

The parish church of Falkenham, St Ethelbert’s, is at the other end of the village, hidden from the road by houses and trees.

The church sits at the very edge of the marshes, looking across the Deben to Ramsholt. St. Ethelbert was a Saxon king of East Anglia who was murdered by King Offa of Mercia in 794. There are only 18 churches dedicated to him in England. He is buried in Hereford.

St. Ethelberts Church, Falkenham.

One could be miles from anywhere in this churchyard but…..

…..we are not that far from Ramsholt.

The view from the Falkenham churchyard across the marshes and the Deben

The beautifully carved west doorway

There is no mention of a church here in the Domesday survey, but it is known that there was a vicar here in 1307 which suggests existence of the church before the late 14th century for which there is physical evidence. I am told that a drawing of the church in 1741 by Kirby depicts lancet windows of 12th century, rather like Waldringfield. The font and tower date from the 15th century. The tower, constructed of flint flushwork, is very pleasing to the eye and the whole ambience of the churchyard breathes relaxation with its birdsong and the fragrance of wild flowers. The west door is original.

Whatever its age, the chancel was deemed to be ‘ruinous’ in the 16th century and, by the late 18th century, so was the nave which was then faced with brick. An apse was added about 1842.

Inside, the hammerbeam and arch-braced roof structure carries winged angels and crowned figures with shields. Most of them have been renewed over time, it seems, but they are said to be ‘true to the originals’ so one presumes the originals survived the iconoclastic destruction of the 17th century.

The hammerhead and arch-braced roof …..

…..with winged angels and crowned figures with shields

The church was much restored in 1903.

At the start of this project, I suggested that the Trimley churches should be included because, before the building of the river walls, Kingsfleet was a much greater expanse of water and its origin is likely to have been about one hundred yards from the Church of St Martin, and the Mariners (Inn) opposite. But, of course, the Trimley churches are also very close to the Orwell; which community would the churches and the pubs in Trimley St. Martin and Trimley St Mary have served, I wonder; those using Kingsfleet off the Deben or those using New Fleet off the Orwell? Probably both, I would think, but today the geographical allegiance of the Trimleys is very much toward the Orwell.

Beyond the Trimleys, in our quest to reach the North Sea via Churches of the Deben we come to Walton, described by Roy Tricker in the church guide as ‘one of the least noticeable and hacked about of the 505 mediaeval churches’ in Suffolk. Out of fairness he does go on to say that when we examine its treasures and mysteries we begin to see the tremendous amount of beauty, antiquity and interest…..’

The church was locked when I visited but just looking at the outside north wall I could see where he was coming from. The church as one views it from the road was largely rebuilt in the nineteenth century but viewed from the north side it presents almost a complete history of church building since the 14th century. In addition, there is a purposefully retained piece of original buttress at the south-west corner which gives the visitor a very good idea of how walls and towers were built using rubble and locally sourced septaria. It is a miracle that any such structure remains standing for centuries and no surprise that some of the towers have succumbed, Alderton being the prime example.

The tower and south wall of The Church of St Mary, Walton – as seen from the road

The north wall of Walton Church – a lesson in church architecture through the centuries

Ancient to the left – 19th century (Victorian) to the right

Showing the retained buttress

… and its soft septarial construction

Walton, today, is removed from the River Deben and, like the Trimleys, its inclusion in Churches of the Deben might be debatable. That is where Roy Tricker’s ‘interest’ part of the church in Walton comes in, because Walton, when it was near to Kingsfleet, prior to any thoughts of river walls, was the site of a Priory. Stanley West, writing for the Suffolk Institute in 2014, describes how a ‘Benedictine cell at Walton was stripped [an archaeological term] in 1971’. The site was described as being 200 metres to the north of St. Mary’s. As there was no sign of an associated church it is presumed that the Church of St. Mary was used for that purpose, much the same as St Mary’s in Woodbridge was the church for the Priory there.

It is very likely that the clergy from that Benedictine establishment would have entered the

chancel through the priests’ door.

The original priests doorway into the sanctuary with the Victorian replacement to the left of it.

East of St Mary’s and the site of the Priory is the Church of St Peter and St Paul in Old Felixstowe, described in its guide as once ‘in a tiny hamlet at the end of a lane leading to the sea.’ In those days Walton was the main village, and the hamlet was a subsidiary community which would eventually grow and become Felixstowe. Today the Church stands about 400 metres from the beach of old Felixstowe and one could be forgiven for thinking that it might not be a Church of the Deben. However, closer topographical examination shows that the church is only 200 metres from the edge of the reclaimed marshland which, in its time, would have been covered by waters of the Deben. In many ways this medieval church is similar to Bawdsey, right down to the loss of a third of its tower, in this case thanks to the weakness of septaria. I imagine that when its tower was full height it would have been a navigational aid to mariners both out on the North Sea and in the Deben.

The Church of St Peter and St Paul, Old Felixstowe. The foreshortened tower is original (but patched) but the rest of the church was built mainly in the 19th century using rather strange techniques. Note the sanctus bell which appeared for the first time in the 19th century rebuild and now looks, at first glance, like a chimney. The north transept (not seen here) was built in 1988.

Septaria and brick patchwork in the south wall of the tower

Rather odd 19th century brickwork

Today, Felixstowe is a seaside town, projecting as a southward peninsula. Its northern border fuses with Walton, its western aspect and its docks are Orwell based and its narrow, eastern extension ends at Felixstowe Ferry at the mouth of the modern-day Deben. We know that in medieval times the waters of the Deben would lap the northern shores of the area but we know also that the building of river-walls and the reclamation of land has distanced the Deben from the urban development which is now Felixstowe. It stands to reason that any church built in the town of Felixstowe after the physical alteration to the river cannot be a Church of the Deben. The near cliff-top Church of St John the Baptist, built in the last decade of the 19th century is a case in point; so, too, are the Ecumenical Church built in the 1930s and the 20th century St Andrews, built of marmitean (don’t test that in the Thesaurus!) concrete.

There is one exception; the medieval Church of St Peter and St Paul. The church guide explains how this church was quite possibly built just prior to 1362 when there was mention of Fylechestow Church. It also explains that it arose from a Benedictine Priory built in 1105 and dedicated to St Felix.

What is not clear to me is whether this last-mentioned Priory is the same as the one stripped in Walton in 1971 or whether there were two, or even more.

I say, ‘even more’ because early and medieval Walton does not seem to have stopped where it does today. There was a castle – Walton Castle – the remains of which may be seen at low water at times of a spring tide just off the beach at Old Felixstowe. In February 2024, when the tide was 0.2 metres, Dr. Sam Newton took photographs which show what seem to be ruins.

Drawings of Walton Castle, made in 1623, show forward projecting towers and rounded corners very similar to Burgh Castle which still stands, near the mouth of the river Waveney. Built by the Romans in the 3rd century Walton and Burgh castles were part of a series of defensive forts known as the ‘Saxon Shore’. The reason for the name is the subject of debate but generally it is thought that they were built by the Romans in an attempt to keep out invaders such as the Saxons.

The fort was used by the Normans and, later, developed further by the Bigod earls. Wikipedia tells us that ‘in about 1170–80 Roger Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk, invited the monks of Rochester to found Walton Priory, dedicated to St Felix, in the precinct of the Roman fort.’

The Bigods appear to have fallen foul of Henry in the late 12th century and it is said that the King arranged for the castle to be dismantled, at least in part, possibly using some of the stone in the construction of Orford castle. About 1317, when the sea was beginning to complete the destruction of the castle, the Priory was relocated to the area of Abbey Meadow, just north of the church of St Mary in Walton, so the Castle Priory and the Benedictine Priory in Walton are one and the same, in foundation at least.

The remnants of Walton Castle appear to have fallen into the sea in the mid-eighteenth century when their disappearance was recorded in Kirby’s Suffolk Traveller (1754) and in Grose’s The Antiquities of England and Wales (1786)

Wikipedia may be quoted as saying that ‘there is some evidence that Walton Castle included in its walls a church dedicated to St Felix.’ There is certain speculation that this church was the ‘Dummoc’ referred to by the Venerable Bede as the seat or See of East Anglia’s first bishop, Felix of Burgundy, in the seventh century.

Simon Knott in his Suffolk Churches website makes good arguments for ‘Dummoc’ being a church at Walton Castle rather than Dunwich and he invites anybody interested to access Dr Sam Newton’s ‘Wuffings’ website, at the same time stating that there appears to be emerging ‘a rich and fascinating picture’ of ‘a lively culture in the 7th century around the mouth of the Deben’.

Wuffings, of course, was the family name of the Saxon King Redwald who converted to Christianity and is buried at Sutton Hoo. The point is made by Simon Knott that Sutton and Rendlesham, the royal capital, are only seven and ten miles respectively from Walton and that it was Redwald’s son, Sigebert, also a Christian convert, who invited Felix of Burgundy to set up a church in East Anglia.

Dunwich, more distant, is the other contender for the privilege of being the first seat or See, clearly more favoured as such by authorities in the Anglican Church.

I do not wish to explore the pros and cons of Walton Castle and Dunwich as the first See because I have absolutely no expertise in these matters. However, for the purposes of this essay, it is interesting to explore the relationship between a Priory, and possibly a church, in Walton Castle and the river as it was then, just as we need to explore the relationship between Benedictine cells and the river and the Church of St Peter and St Paul.

To do that we need to consider another of my dreaded doodlemaps, designed to ‘give an idea’ without any pretence of geographical accuracy!

The map shows St Mary’s, Walton, the Church of St Peter and St Paul, Old Felixstowe and Walton Castle lying almost in a straight west-east line and none of them much removed from what, in their time, would have been the river Deben.

There is one more church to add to our list – the Church of St Nicholas at Felixstowe Ferry. It is seen from the road which passes across the golf course from Old Felixstowe to Felixstowe Ferry.

Across the links, to the right, and close to a Martello tower this little church is easily missed. It was founded in 1878/1879 as a combined school and church and it started life as a corrugated hut, known as ‘The Schoolroom’. In 1943 it suffered bomb damage which left it unusable. Services continued in a hut which was lent by the golf club, but in 1954 they resumed in the current building, a simple structure dedicated to St Nicholas, the patron saint of seafarers.

It might be argued that this is a Church of the North Sea, such is its proximity to the sea, but it is the Church of the Felixstowe Ferry community and one can’t ask for anything more ‘Debenish’ than that.

Prior to the building of the river walls, Kingsfleet would have been much wider and most of the pale green area in the doodle would have been blue, representing water, with Bawdsey, Alderton, Ramsholt, Falkenham and Gulpher, close to the edge of the water. The churches of Walton and Old Felixstowe and the Castle would have been only 2 or 3 hundred yards away with one or more Benedictine priories or cells in a similar situation, within easy reach of the water on low lying land (depicted in the map with seaweed green) The Benedictine cell in Walton was known as Walton Abbey in an area known as Abbey Meadow.

The Church of St Nicholas at Felixstowe Ferry is easily missed as one drives across

the golf course bound for the Ferryboat Inn or the foot ferry

The end of the road – Felixstowe Ferry – Bawdsey opposite.

So there we have it – a whistle-stop tour of the Churches of the Deben. Each time I count them I get a different number, but it is somewhere between 43 and 45.

Now, you know from part 1 that I like a bit of arithmetic fun!

If we divide our winding river into an upper section and a lower estuarine section we find that the approximate length of the upper section, a simple stream or river from the source to a point between Bromeswell and Melton, is in the order of 20 miles, 20 miles of countryside in which to build churches. The approximate length of each of the banks of the estuarine section, as they were before the river walls, is 12 miles, making 24 miles of riverbank, 24 miles of riverbank on which to build churches.

So, the River Deben provides a total of 44 miles of church building potential and we have identified how many churches? – 44, one per standard winding mile (1760 yards). If they were Suffolk miles (1830 yards) we would only need 42 churches!!

I can only end by quoting WG Arnott who said ‘it is not easy to write the story of a river: …… nine hundred years of recorded history is a long time for a long winding river.’

Dr Gareth Thomas MD., LL.M., FRCOG

Gareth Thomas retired as a local Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in 2010 and left the medicolegal world of Expertise in 2015. He and his wife Alison moved to Waldringfield from Rushmere Road, Ipswich in 2006, having previously lived in Nacton for nine years from 1979 – so they are getting to know the South Suffolk peninsula reasonably well! In 2007 Gareth became a founder member of the Waldringfield History Group and for ten years from 2010 he was Chairman of the Group. The end of his tenure of office coincided neatly with the publication of Waldringfield – a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben. The book was a combined effort on the part of all members of the small Group, but Gareth was one of the three members who took responsibility for the editing and management.

Gareth Thomas retired as a local Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in 2010 and left the medicolegal world of Expertise in 2015. He and his wife Alison moved to Waldringfield from Rushmere Road, Ipswich in 2006, having previously lived in Nacton for nine years from 1979 – so they are getting to know the South Suffolk peninsula reasonably well! In 2007 Gareth became a founder member of the Waldringfield History Group and for ten years from 2010 he was Chairman of the Group. The end of his tenure of office coincided neatly with the publication of Waldringfield – a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben. The book was a combined effort on the part of all members of the small Group, but Gareth was one of the three members who took responsibility for the editing and management.

Never known for sitting about, Gareth may be seen around Waldringfield walking his dogs, on the water on ‘Blazer’ or crabbing with some of his younger grandchildren. He is also too well known (in his opinion) for his involvement in the village pantomimes.

For the last twenty-three years he and Alison have had a family home in the valley of the Vezere in south-west France where Gareth has been able to maintain a managed meadow and plant well over one hundred trees.