By Liz Hattan, RDA Vice Chair

We are so lucky to live near the River Deben – many of us enjoy sailing and kayaking on it, walking by it, or swimming in it. It’s also special for its wildlife and landscapes resulting in it being designated under international and domestic law to help conserve it.

The Deben Estuary is designated under international law by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and under domestic law (England and Wales) as a Special Protection Area, as well as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and as part of the Suffolk and Essex Coasts and Heaths National Landscape (previously known as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty AONB).[1] But why has the Estuary received such designations and why does it matter? In summary, it is designated because of the Deben’s unique and invaluable biodiversity and special landscape features; by having such designations it makes it easier to protect and conserve the area, both legally and because it helps remind us all to take extra special care of it.[2]

Curlew (courtesy Sally Westwood)

Ramsar Site

Wetlands are land areas that are saturated or flooded with water either permanently or seasonally, including inland wetlands such as marshes, lakes, rivers, floodplains, swamps, and coastal wetlands such as saltwater marshes, estuaries, mangroves and lagoons.

The Convention on Wetlands is the intergovernmental treaty that provides the framework for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources. The Convention was adopted in the Iranian city of Ramsar in 1971 and came into force in 1975. Since then, almost 90% of UN member states, from all the world’s geographic regions, have acceded to become “Contracting Parties”.

The Deben Estuary from Felixstowe Ferry to near the tidal limit just above Wilford Bridge was designated as a Ramsar site in 1996 (an area covering nearly 1000 ha).[3] Such sites are wetlands of global importance that have been designated under the 1971 Convention for their biodiversity and rare or unique wetland features. There are currently 172 countries signed up to the Convention. In England, Defra is the lead authority with the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) providing scientific advice and practical support, including coordinating the production of the UK National Report to the international Ramsar meetings.[4]

In England there are 69 Ramsar sites, totalling an area of 327,976 ha. Many of these sites have been designated in whole or part because of their importance to waterbirds. The Deben is designated because its large areas of saltmarsh and intertidal mudflats support nationally and internationally important flora and fauna, in particular brent geese and a population of the endangered mollusc vertigo augustior (whorl snail) at Martlesham Creek (which is one of only fourteen sites in Britain where this species survives).[5] Locally, the Stour and Orwell estuaries, as well as the Alde and Ore Estuary are also designated Ramsar sites.

Redshank (courtesy Sally Westwood)

Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)

As international law has no direct legal weight in the UK, Ramsar sites typically have legal protection by being designated under domestic law as SSSIs under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981and/or as Special Protection Areas (see below).

For the Deben Estuary, that means the entire stretch of the Estuary from Felixstowe Ferry to just above Wilford Bridge is designated as a SSSI (the site partially overlaps the boundaries of two geological SSSI at Ferry Cliff, Sutton and Ramsholt Cliff). According to its designation, the ‘Deben Estuary is important for its populations of overwintering waders and wildfowl and also for its extensive and diverse saltmarsh communities. Several estuarine plants and invertebrates with a nationally restricted distribution are also present’.

Whilst some aspects of the site are in favourable condition, the last condition assessment by Natural England of the Deben SSSI in 2022 considered that the reedbeds were in an unfavourable and declining condition meaning that external pressures need to be addressed in order to reverse the decline[6]. The cause of this is not entirely clear and as part of its water quality investigations, the ‘Recovering the Deben’ project[7] is looking at this and working with Natural England to help redress the decline (for further information, see the recent RDA Journal article by Colin Nicholson on water quality).[8]

Shell Duck (courtesy Sally Westwood)

There are over 4,000 SSSI’s in England, covering more than 1.1million hectares. Natural England oversee the SSSI regime and recommend which sites should be designated, typically due to their fauna and flora, geology or landforms, and they are also responsible for carrying out condition assessments. Many SSSI’s are on land that is privately owned, and such designation aims to help conserve the site through appropriate management. All SSSI’s are registered on the Land Charges register. Owners must manage such sites effectively and appropriately to conserve the special features of the site, such as by grazing animals at particular times of the year, managing woodland and controlling water levels. Consent from Natural England is often required to carry out activities on the site, and there are also additional controls on development. Public bodies, such as local authorities and statutory bodies (eg water and electricity companies), must also consider the potential impacts on SSSIs of any of their activities. Failure to do so could result in a criminal offence, including a fine.

Special Protection Area (SPA)

In legal terms, the Deben Estuary attracts most protection through its designation as a special protection area (SPAs). SPAs are protected areas for birds classified under the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 and overseen by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee.[9] As stated by the RSPB, ‘Governments are required by these laws to take appropriate steps to avoid pollution or deterioration of SPAs, or any significant disturbance affecting the birds’.[10] There are 82 SPA sites in England covering nearly one million hectares. The Deben Estuary was designated as a SPA in 1996 (the same time it was designated as a Ramsar site) primarily due to its populations of brent geese and avocets, as well as a range of other breeding and wintering wetland birds such as shelduck, gadwall, teal, redshank, oystercatcher and curlew.[11] Most proposed development / activities on a SPA require a habitats regulatory assessment to be carried out before permission is granted in order to ensure there will be no significant effect of the proposal on the site – this includes a detailed assessment of the site and an experts opinion of the impact of the development/activity on the site. This makes it much more difficult to get planning permission for example, even for relatively small projects.

Avocet on the Deben (photo by Richard Verrill)

National Landscape

National Landscape is the new name used to describe the UK’s Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Areas are designated by Natural England who can make orders for new sites and vary existing boundaries, as for the Suffolk and Essex Coast (see below). About 15% of England is covered by such designations. Legally, they are still known as Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and are protected under the National Parks and Access to Countryside Act 1949 and the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000. The purpose of the designation is to help conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the area. This means that before certain activities are carried out or planning decisions made, consideration must be given to the conservation and enhancement of the area, although it doesn’t necessarily mean that it prevents those activities or development taking place.

Oyster Catcher (courtesy Sally Westwood)

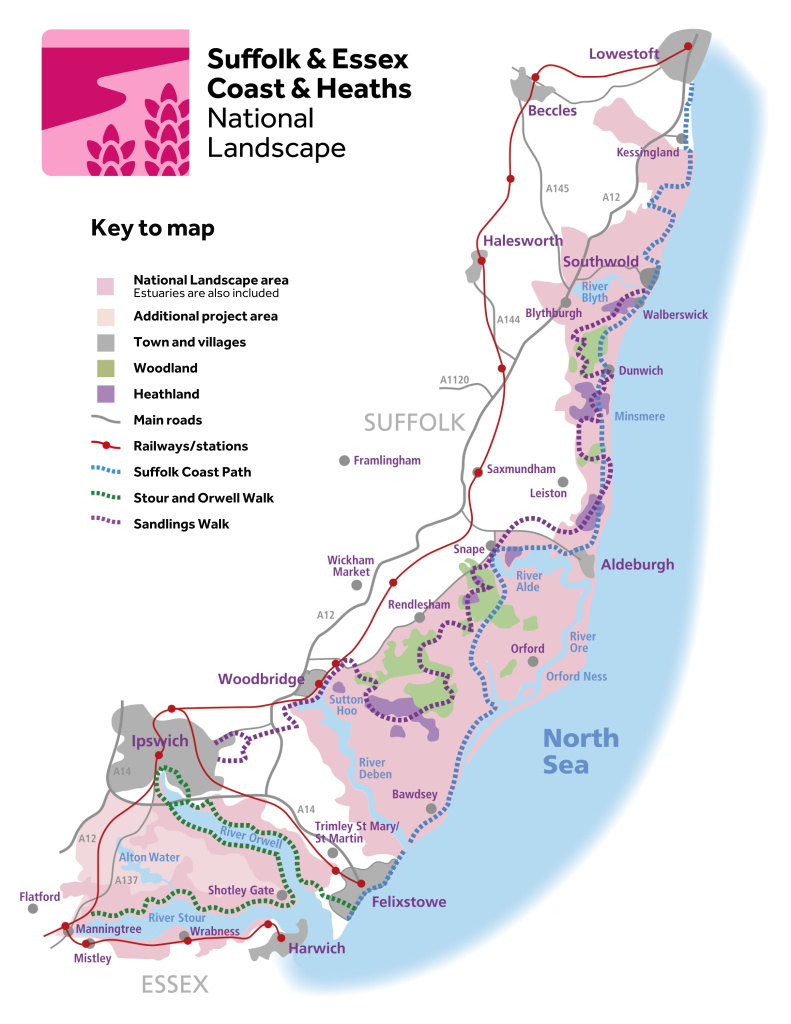

Unlike the Ramsar, SPA and SSSI designations above which focus on the Deben Estuary, the Suffolk and Essex Coast and Heaths National Landscape stretches from Kessingland in North Suffolk, down to the Stour Estuary in North Essex, so including the Deben, and covering 441 square km.[12] This was established in 1970 and extended into Essex in 2020 to include the southern shore of the River Stour, the Stour Estuary itself, Samford Valley and Freston Brook. In 2021, the National Landscape/AONB selected the redshank as their flagship bird as part of their Nature Recovery Plan.[13] Their Management Plan[14] for the period 2023-28 sets out the opportunities and the threats facing the area, taking into account the requirement to conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the area. One of those threats is the number of Nationally Significant Infrastructure Schemes, including large scale offshore wind projects and a 3rd nuclear power station at Sizewell (see the 2023-28 Management Plan for further information including a list of those Projects).

Map from https://coastandheaths-nl.org.uk

Conclusion

The range and number of designations on the Deben Estuary[15] demonstrate its value as a unique and biodiverse stretch of water, and the resulting legal protections have been important in maintaining its special features and biodiversity. Given the importance of these designations, it is worth keeping an eye on the provisions in the Planning and Infrastructure Bill. This Bill has just been introduced to Parliament (March 2025) and amongst other things aims to change the way such designated sites are protected with the intention of providing for a more strategic approach by setting up a Nature Restoration Fund and Environmental Delivery Plans.[16]

Teal (courtesy Sally Westwood)

Liz Hattan

Liz Hattan is an environmental lawyer, RDA Vice Chair and a member of the RDA Conservation Sub-Committee.

References

[1] To see all designations, see the MAGIC website which is interactive and provides authoritative geographic information about the natural environment drawing on 400 data sets including legal designations – https://magic.defra.gov.uk/MagicMap.html.

[2]See RDA article on protecting wildlife when canoeing, kayaking and paddleboarding https://www.riverdeben.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Protecting wildlife when canoeing, kayaking and paddleboarding on the Deben – 2021 maps.pdf

[3] https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/794

[5] Here is the link to the official Ramsar Information Sheet submitted to the Ramsar Convention by the JNCC in 1996 https://jncc.gov.uk/jncc-assets/RIS/UK11017.pdf

[4] https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/ramsar-convention/

[6] https://designatedsites.naturalengland.org.uk/SiteFeatureCondition.aspx?SiteCode=S1006262&SiteName=Deben Estuary SSSI

[7] https://www.essexsuffolkriverstrust.org/recovering-the-deben

[8] https://www.riverdeben.org/rda-journal/water-quality-update/

[9] Special Protection Areas | JNCC – Adviser to Government on Nature Conservation

[10] https://www.rspb.org.uk/helping-nature/what-we-do/influence-government-and-business/nature-protection-and-restoration/nature-designations-england

[11]https://jncc.gov.uk/jncc-assets/SPA-N2K/UK9009261.pdf.

See also the article by Sally Westwood on The Importance of the River Deben for birds https://www.riverdeben.org/rda-journal/the-importance-of-the-river-deben-for-birds/

[12] https://coastandheaths-nl.org.uk. The name Suffolk Coast & Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) was changed in November 2023 to Suffolk & Essex Coast & Heaths National Landscape,

[13] See article by Sally Westwood on birds of the Deben including the focus on the Redshank – https://www.riverdeben.org/rda-journal/our-birds-on-the-deben-what-can-we-do-to-help-them-focus-on-the-redshank/

[14] https://coastandheaths-nl.org.uk/managing/management-plan/

[15] To note also the recent designation of the bathing water at Waldringfield which this article does not address given it focusses entirely on its use for swimming – see the article by Colin Nicholson at footnote 8 above