By Ned Jones, Julia Jones and Bertie Wheen

and with acknowledgement to the book Waldringfield: A Suffolk Village beside the River Deben (Golden Duck 2020).

Kestrel Sail Emblem

Box containing the designers name (J Fancis Jones)

The birth of the Kestrel in Waldringfield (Julia and Bertie)

The Kestrel class of small, wooden cruiser-racer yachts was conceived in Waldringfield in the mid-1950s, then spread across the country during the 1960s and 70s. 150 were built in wood, 250 in GRP. Their story began when local sailor Paul King, who had owned a Waldringfield Dragonfly, wanted a small yacht with similar characteristics. He and Harry Nunn – of Waldringfield Boatyard – built a model to embody their ideas, then took it to Jack Jones at the Old Maltings to finalise the design and provide the necessary technical details.

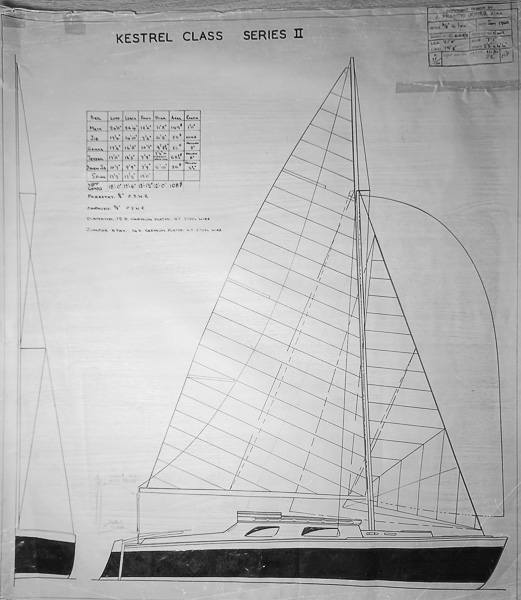

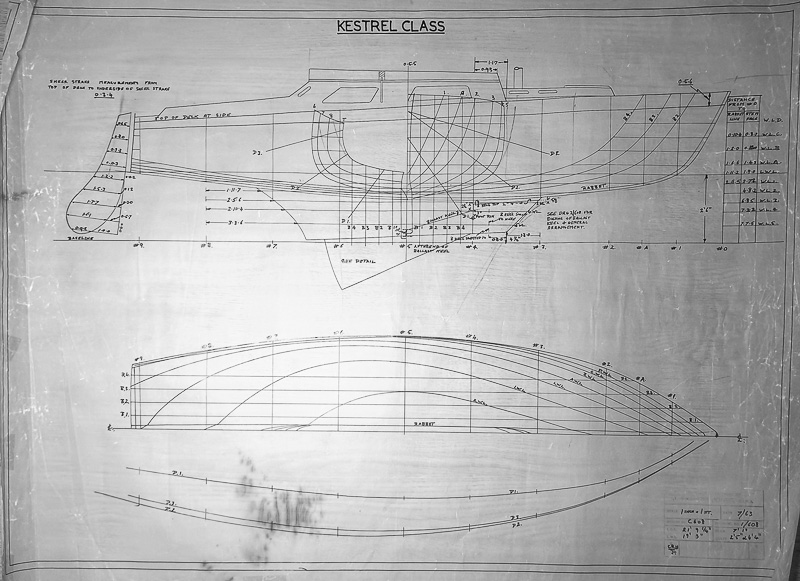

Kestrel plans

Jack was a professional naval architect whose designs had first been published in Yachting Monthly by editor Maurice Griffiths in the years immediately before WW2. He, and his younger brother George, were tenant farmer’s sons from Witnesham who weren’t particularly interested in the land but loved the river. When their war service was over, they wanted nothing more than to get back to the Deben and spend their life with boats. Jack and their mother Edith bought the Old Maltings which was then in a rundown state. He established his yacht design business on the top floor, enjoying its wonderful views across the river, while younger brother George (later the father of Julia, Nick and Ned) converted the stables at the back of the house into the East Coast Yacht Agency.

Jack Jones

Sailing entered a period of increasing popularity in the post-war years and George was soon able to move the yacht agency to more convenient offices in Quay Street, Woodbridge, while Jack took on apprentice draughtsmen in Waldringfield. Two of these, Alan P Gurney – who moved to New York to design fast ocean racers – and Christopher Rushmore ‘Kim’ Holman, would become internationally well known. Holman produced plans for countless boats such as the Stella and Twister classes. He was also a founder director of Suffolk Yacht Harbour. A third apprentice draughtsman, Peter Brown, remained local, worked with Jack for most of his design career and founded Brown and Overbury, the respected firm of yacht surveyors.

The first wooden Kestrel, Flare, was built at Waldringfield Boatyard by Ernie Nunn. She was found to sail beautifully – ‘like a dinghy’, according to many subsequent Kestrel owners. Flare was 22’, clinker-built and gunter-rigged, with a small keel and retractable centre-plate, but all later Kestrels have been Bermudan rigged. Some have small inboard engines; others rely on outboards when the wind dies, or they are trying to push out of the river against the tide. Their shallow draught makes it possible for them to explore the smallest creeks, while their generous sail area suited the more competitive spirits of the Waldringfield Sailing Club who built up a small class for racing. Some of the later GRP kestrels have twin bilge keels, enabling them to stand upright when they dry out.

Deben Redshank on her bilge keels

The business partnership of Jack and George ensured that the class spread beyond Waldringfield. Kestrels were built at boatyards across the country, including Larkman’s and Robertson’s at Woodbridge, King’s of Pin Mill, Hall’s at Walton-on-the Naze and also in Hull. In total 150 wooden Kestrels were built: the majority 22’ but others a little longer, 24’, plus a sister class of Peregrines.

White Cloud – This photo was used to advertise the Kestrel class

The Peregrine class were the Kestrel’s bigger sisters

Run, run as fast as you can. You can’t catch me, I’m the Gingerbreadman (Ned)

I was brought up on boats, my Dad was in the business. And as a baby I swung over my Mother’s bunk in a wee pipe cot. So, the motion and sounds of a wooden boat have always been with/in me. I was eventually ready and able to buy my own boat with £3,000 from my father’s Will. I found Gingerbread Man, a Kestrel 22’ Mk II, up Flag Creek, off the Colne near Brightlingsea.

I was mindful of the hours of loving and meticulous attention my Dad gave to Peter Duck, especially around keeping her decks sound, and was cautious to take on that commitment for a wooden boat but was grateful to Richard, from the Tidemill Yacht Harbour, who accompanied me on the prospecting visit and helped me take a leap of faith and said I could at least “manage her decline”.

I never guessed she would give me 30 years of pleasure.

Ned at the helm

George Jepps, the great yachtmaster instructor from Harlow, helped me sail her home from the Colne to the Tidemill. We had excitements, made mistakes – we even touched bottom sailing in too close to Walton Castle with the centreboard down. Through it all she performed like a fast and handy dinghy, particularly when my mother, June, took the helm. She was so quick, so light and responsive.

In the winter, when I was struggling with the fitting out, I would tell myself that she was only a dinghy with a cabin, but in fact, when I needed her to be a boat, she certainly was one. When I sailed her to Calais once she travelled up one side of a Channel swell and sailed on down the other side, quite resolute – I felt safe out there all alone with me, the wind and the sea, and a boat so fit for purpose.

She was fit for it, but I never was again – one crossing to Calais was enough for me. My friend was suffering a dangerous bout of food poisoning as we left France and I was shouting to help her retain consciousness as Ginger sailed us to Ramsgate where there was an ambulance waiting.

Having been spared, my fun was back on the East Coast rivers, particularly sailing with my older daughter Ruth, who has been on board ever since she was a baby. For a while Ginger and I returned to the Colne. She was moored on the piles at Brightlingsea, then I berthed her for some seasons at Wivenhoe whilst I lived in that village.

Ruth as a baby on board

But her real home was always the Deben……even when I lived far away in North Scotland at Findhorn, near Inverness or more recently in Berlin. I was born in Woodbridge have always been drawn back either to sail or to fit out. Ginger has spent winters in all the Deben Yards: the Tidemill, Mel Skeet’s, Felixstowe Ferry, Eversons (later Woodbridge boatyard), Larkmans, Robertsons, Martlesham. When I did a few weeks teaching practice at Waldringfield Primary School, I lived on board. Her regular moorings have been the Tidemill (so easy to get on/off); Felixstowe Ferry (so atmospheric and sometimes wild), then finally the peace and beauty of Haddon Hall/Methersgate.

By this time Ruth was learning to skipper her own vessel on a reservoir near London and Louisa, her much younger sister was the new baby on board.

Lou doing the washing up

In the end her fabric was decaying faster than I could keep pace – despite my nephew Bertie’s valiant efforts with the gunge gun every spring, helping me fill the gaps between her lightweight clinker planking. I loved her wooden construction, it seemed to have a particular warmth and life. But Ginger was dying. She was no longer safe to venture out of the river; she sunk on her moorings when I was far away in Germany; I didn’t feel confident to let Ruth sail her alone. An advertisement offering her as a rebuild project brought no serious response, so finally, this summer 2024, I had to let her go.

I feel privileged to have had an upbringing on the sea and though I found I had not really learnt the detail of what it takes to care for a wooden boat, I had got the feel for it and the confidence to buy into it all those years ago – to take my Dad’s inheritance and set it sailing again.

Ned with sails up

Gingerbread Man RIP (Ned)

Ginger was/ is my love.

She gave me the experience of being so alive!

Especially reaching to windward – we were “power and motion in balance”.

She was cute cos she only drew two foot six.

It meant I could go most places and still be afloat.

Ultimately the decay of my body and her body pretty much tracked each other.

When I was strong, I and crew could do a cracking fit-out and sail her on the edge.

When I was weak, she suffered and leaked.

She gave me a cradle for my life and adventures.

She gave my two daughters a love of the sea and small boats.

She hosted my companions over the years,

Thank You, Ginger.

Ruth Jones taking Gingerbread Man downriver

Gingerbread moored in the Deben

The Last Wooden Kestrel on the Deben? (Julia)

One of the reasons Ned put off the final end of Gingerbread Man was that he – and we – believed she was the last wooden Kestrel on the Deben. Sally Brown, the last Kestrel in Waldringfield, had finally gone on the bonfire in the same yard that she had been built and we’d noticed various dejected sister ships in Andy Seedhouse’s Woodbridge yard. Deben Redshank and Nooka are among the GRP Kestrels still giving pleasure on the water. When Bertie and I were part of the Waldringfield book production team (2020), we stated with some confidence that Ginge was the last (wooden) survivor.

Deben Redshank (GRP Kestrel)

But we were wrong! One day, Ned was passing the Tidemill Yacht Harbour where he and Ginger had such happy times, when he saw a sweet – and beautifully maintained – small wooden Kestrel. This was Caraway. She had been built at Robertson’s in 1963 and was clearly in great condition, keeping the Deben heritage, and the legacy of our uncle Jack Jones, alive. It made saying goodbye to Gingerbread Man a personal (and family) sorrow, not the end of an era.

Caraway

Now Caraway’s owner must go and live abroad and she is therefore for sale. If you are walking along the river wall past Woodbridge Boatyard, glance over and you will see her – reminiscing with Peter Duck perhaps? I hope so. I also hope she will find a new owner and this line of charming small yachts, so evocative of their period, so much part of our river, will last a little longer.

Caraway in Tidemill

Editor’s Note:

Boats Still Floating 2025

In January 2025 we will begin a year long project to collect the details of as many boats built in 1950 and before which are still in use on the Deben. These can be large or small – dinghies and liveaboards are included – the only criteria is that they still float. We will need our readers’ help.

Meanwhile we wish you all a very happy Christmas.

Julia Jones