By Julia Jones

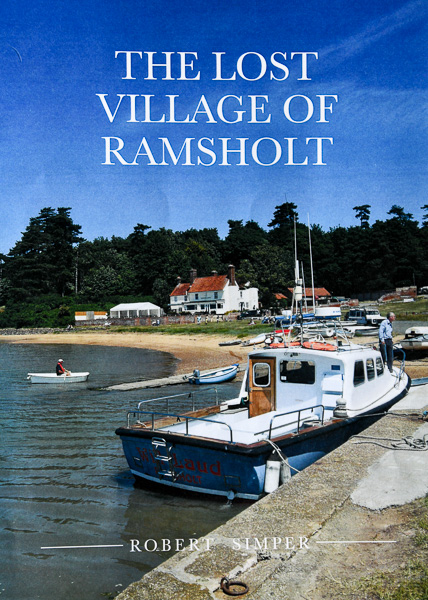

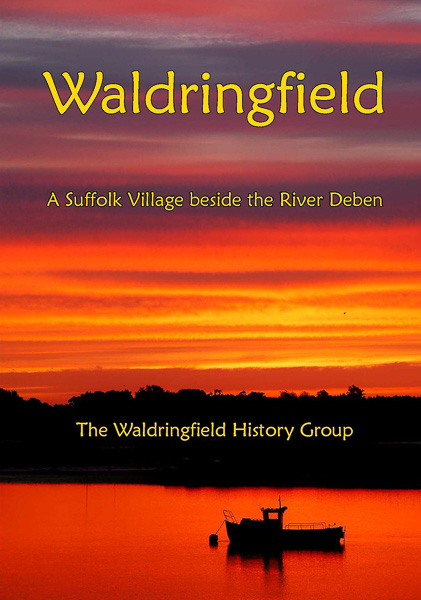

2020 was the year that saw the publication of two significant histories of two of the river Deben anchorages – and their associated settlements. The Waldringfield History Group just got there first with Waldringfield a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben published at the end of September (for Michaelmas, as it happened). Then, within a month, came Robert Simper’s The Lost Village of Ramsholt a slim book which I think will hold a special place within his distinguished career as a Suffolk historian. It feels like a particularly personal book beginning, as it does with his and Pearl’s wedding in 1959 and their move to what was already an ‘isolated’ cottage and would very soon become more so as the Ramsholt villagers moved – or were moved – away. “That young couple will not last long stuck down that dreadful lane, One winter and they will be gone.” But Robert and Pearl stayed, playing their Elvis Presley records, bringing up their family, being part of local change as well as witnessing and recording it.

2020 was also the 30th anniversary of the founding of the River Deben Association. Our new Chairman Joeske Van Walsum took the opportunity to talk with Robert Simper, our perennial President. Their conversation was professionally recorded and is an auditory as well as a visual delight. If you’ve not yet watched it, please do.

Robert Simper dropped in a fact which started me. “At the beginning of the eighteenth-century,” he said, “Ramsholt and Waldringfield had the same size population” How different they look now!

Ramsholt is indeed a Lost Village in material terms. I am old enough to remember the church cottages which were pulled down in the 1960s, completing the destruction of what had been a populated agricultural community. I feel their ghosts when I woke up that lost lane from the water meadows to the church. My parents are buried up there, along with many others from the past. If the poet Thomas Grey had wanted to write a riverside version of his Elegy in a Country Churchyard he should have come and sat a while up there, surrounded by Wallers and with that timeless view down towards the sea. It’s never a mournful or a lonely place, and neither is The Lost Village of Ramsholt. Robert Simper’s book is full of the voices of those people from the past. He’s a good listener, always learning from the people who might know how to find their way by the stars and the most effective methods of exterminating rats. His boyhood mentors and former neighbours came back to life, experienced, opinionated and sometimes just plain wrong. “I don’t know what the fuss is about over those old carved beams,” one of them said during the demolition of a grand mediaeval hall. “If you’d given me some tools, I could have carved them.”

The Lost Village of Ramsholt closes with new voices heard during the strange summer of 2020: First there was an eerie silence, as people were living in lockdown to slow the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic (as we are again at the time of writing) then restrictions eased and people felt desperate to get out into the countryside after weeks indoors. In Ramsholt Johnathan and Claire Simper opened ‘Wild Camping’:

Two different worlds met. On the bottom of Wallpond field, overlooking Shottisham Creek, the cheerful southern English voices drifted across the grass, while at the top a huge potato harvesting machinery created clouds of dust, lifting a well-irrigated crop. We had seen total crop failure in the past, in 1976 when it was a very hot summer and no rain, now at least some crops could be saved. Time never stands still.

Jimmy Quantrill (former barge skipper) on Waldringfield beach c 1946

Jimmy Quantrill (former barge skipper) on Waldringfield beach c 1946

The village of Ramsholt may be irrevocably lost yet a sense of community and humanity and welcome remains. This is something of an achievement. In Robert Simper’s 30th Anniversary interview, he continually returns to the need to balance welcome, tranquility and the basic need for economic health. I can remember how startling it was when the first of those irrigation systems came to the light soil of Sutton Heath and the fields on the “other side” of the river.. What had been poor, friable infertile land was suddenly transformed into something special. It provided ideal conditions to produce early potato and carrot crops, ground in Suffolk not imported from abroad. Yes, it’s sad that where there were fifty people working there are now four people and large machines but would we have wanted to endure that back-breaking labour and poverty of earlier times? Consider the ‘mudders’ and the coprolite-washers photographed in the Waldringfield book. Give me a JCB any day!

Agricultural change, as it affects landscape, is often contentious – usually from the point of view of those not involved. What shocked me most deeply in The Lost Village of Ramsholt was the period during which pheasants were privileged over people and shooting was more important than living space. Nevertheless much of the beauty and special landscape of the other side of the river derives from the man-made transformations to improve the pheasant shooting.

Ramsholt Church by Jack Merriott (1901-1968)

Ramsholt Church by Jack Merriott (1901-1968)

Having spent a significant portion of last summer labouring on the Waldringfield book, I will never now be unaware of the vanished presence of industrial kilns and chimney stacks forming the cement works around what is now Waldringfield Quay. Imagine how horrified we would all be if such a project were suggested today. Yet it’s clear that it gave the ordinary people of Waldringfield a better standard of living – and more diversions — then they would have enjoyed had they remained dependent on agriculture alone. Fully rural life, through the 19th century, was hard indeed as the produce of the countryside went to feed the increasing population of the towns, especially London. It was in 1851 that England became the first country in the world where more people lived in cities than in the countryside and Waldringfield, because of the river and the beach, became part of that. Among the most memorable photographs are those of barges landing on the beach either to fill their holds with agricultural produce or empty them of “London muck.”

The Waldringfield Cement works were, no doubt, an environmental nightmare but when they closed at the beginning of the 20th century it could have been a disaster for the people in the village. There was a disaster, of course – the 1914-1918 war. But after the war, in the 1920s, despite economic depression, social change, moral uncertainty some people managed to have fun. Waldringfield had what we would now think of as the infrastructure for fun once the motor car, the bike and the bus made it accessible. That same beach which had served as an off-loading point for London Muck could now become a safe surface for rowing and swimming and dinghy sailing or making yourself comfortable in a deckchair to watch a Punch and Judy show. The bargeman and waterman who had been put out of work by the trade depression could turn their skills to instructing some of the young men and women of the leisured classes. Yachting in the 1920s began to become the pastime of a slightly wider social class then it had been in the days of the big yachts and the gentry.

This year, 2021, the Waldringfield Sailing Club will celebrate its centenary and what a wonderful example that was of people from different social groups being brought together by their common interest in in river. Things were different at Ramsholt. The other side of the river was the property of very rich people putting their money in their property. I love the other side of the river I love its seclusion and its beauty and a sense perhaps that’s it’s a place which time forgot.

Yet there are no such places. The divergent stories of Ramsholt and Waldringfield over the past two hundred years reveal the complex interplay between people and the environment. It’s endlessly interesting – though sometimes a little daunting when we begin a new year and wonder what lies ahead.

Julia Jones

Julia Jones is the editor of The Deben magazine. She was born in Woodbridge and spent many happy hours in both Waldringfield and Ramsholt. She still does.